No development has shaken up the cloistered and carefully controlled world of English boarding school life quite as much as the invention of the smartphone. Traditionally, schoolboys might write home once a week. Perhaps they might be able to smuggle in a dirty magazine or other contraband, but for the most part boarders on school grounds were safely tucked away. Today, thanks to smartphones, children are sent to school with access to pornography, internet chatrooms and easy contact with their parents.

What horrors might a group of 13-year-olds get up to in a dorm if left unattended with internet access?

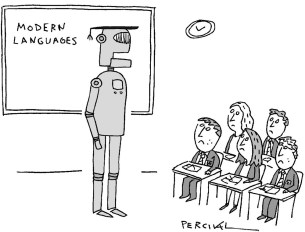

Should boarding school children be permitted to phone home each night? What horrors might a group of 13-year-olds get up to in a dorm if left unattended with internet access? Can parental controls be trusted, or are our teenagers savvy enough to outwit them? What about Educational Technology – ‘Ed Tech’ for short? Is handing out Chrome Books and iPads to pupils the mark of a school at the cutting edge of learning, or naivete destined to disrupt lessons, not to mention sleep?

The approach an independent school takes to these questions will shape the type of education a child receives. There is no consensus between schools on phones, and head teachers vary dramatically on how they’re approaching digital encroachment. For some it’s an opportunity to grant pupils independence; for others, it’s the biggest challenge facing modern education.

Eton has just implemented a new policy in which F Block boys (the youngest group, aged 13 to 14) are given a ‘brick’ Nokia phone, which is only capable of making and receiving calls. It has absolutely no internet access. All boys who joined the school this year were asked not to bring a smartphone with them. Every boy is, however, given an iPad for use only in lessons and for homework. The school says that the policy is an attempt ‘to balance the benefits and challenges that technology brings to schools’.

Jennifer Power, co-founder of the website Smartphone Free Schools Rating, tells me that she’s inundated with requests from parents for information about how different schools navigate the online world. The site awards a gold, silver or bronze badge to schools based on their phone policy (gold is for smartphones banned on site, silver is for locking them up and bronze is for a simple ban on use). The website has, she says, exploded in popularity in the past year.

As more research papers are published about the harms of smartphones on developing minds, Power tells me that ‘we’ll see a big uptick in phone bans at the start of September’. Independent schools, she argues, are ‘able to implement policy much more quickly and thoroughly’ than state schools, giving them the upper hand in this area. Further, despite the fact the Department for Education published guidance on mobile phones in schools last year, encouraging schools to, at the minimum, ban use of phones on the premises, Power has noticed that many head teachers are looking to Britain’s leading public schools as examples of how they should manage phones, rather than the government.

Some schools have come up with creative solutions. St Paul’s Boys’ School, for instance, gives all fourth-form pupils a magnetic Yondr pouch for their phones. The pouches can only be unlocked when tapped against a special station at the end of the school day – using tech not unlike the tagging system on clothes in department stores. This solution allows the boys to phone home in the event of an emergency, with the help of a teacher to unlock their pouch, but it saves a poor member of staff from the responsibility of collecting hundreds of iPhones every morning.

New technology, however, comes with new challenges. Some teachers report that children are coming up with increasingly innovative ways round the pouches: from handing over a ‘dummy’ phone for lock up to hacking the magnetic closure system. Despite this, Yondr has had huge commercial success selling its wares to schools and has expended significant lobbying efforts trying to convince legislators in the United States to make schools go phone-free. In May, the former schools minister, Nick Gibb, Tory MP for Bognor Regis and Littlehampton, was appointed as a consultant at the company. Queenswood, Surbiton High, John Lyons and City of London School for Girls all use Yondr pouches throughout the day, while St Swithun’s in Winchester only permits boarders to remove their phones from their Yondr pouches for an allocated period in the evening.

Pupils have turned to board games such as Scrabble to fill their lunchtimes, rather than Snapchat

Of course, there remain schools that take a more libertarian approach. Westminster School allows pupils to carry smartphones on their person and permits full use in boarding houses at the end the school day. Harrow shares a similarly relaxed policy but does take phones away from boys in the lower school overnight, with more flexibility for sixth formers providing they prove they can be trusted. The headmistress of Benenden in Kent believes that ‘as a boarding school, it wouldn’t be appropriate for us to ban phones outright, because they’re a vital communication tool’, but the school restricts phone time to just 30 minutes in the evening for Year Sevens, with access gradually increasing as the girls get older. One anti-smartphone campaigner told me that boarding schools with a higher proportion of international students tend to take a more relaxed approach to phone policy, prompted by the desire from overseas parents to stay in touch with their children.

Richard Cairns, headteacher of Brighton College, has taken one of the most hardline stances against mobile phones. The school went phone-free as early as 2017, and since then pupils have turned to board games such as Scrabble and Cluedo to fill their lunchtimes, rather than Snapchat and selfies. The numbers of books taken out of the library increased and classroom disruption fell.

The research bears out the benefits of a hard ban. The Times recently found that schools with smartphone-free policies have seen a drop in suspensions, detentions and bullying, while the thinktank Policy Exchange has demonstrated that children attending schools with an effective ban achieved GCSE results that were graded higher when compared with children at schools with laxer policies. In his book Anxious Generations, the American social psychologist Jonathan Haidt blamed smartphones for a decline in the mental health of teenagers, particularly girls.

As for day schools, the case for smartphone bans is clear cut. More than eight in ten parents wish that their child’s school would ban smartphones. Sir Martyn Oliver, Ofsted’s chief inspector, is with them, recently joining the call for the government to act. Two parents, Will Orr-Ewing and Pete Montgomery, feel so strongly about the issue that they are threatening the government with a judicial review if a statutory ban on smartphone use in schools is not brought in.

There is no doubt that smartphones are creating a new set of problems for housemasters and matrons. But once the Pandora’s box has been opened, can it ever be truly closed? Many parents now expect regular WhatsApp updates from their children during term time. Would it ever be possible to return to the weekly letter home? Even the headteachers with the most radical policies on phone usage all permit pupils to use a phone in some form, even if it’s just through limited screen time or a Nokia brick.

Comments