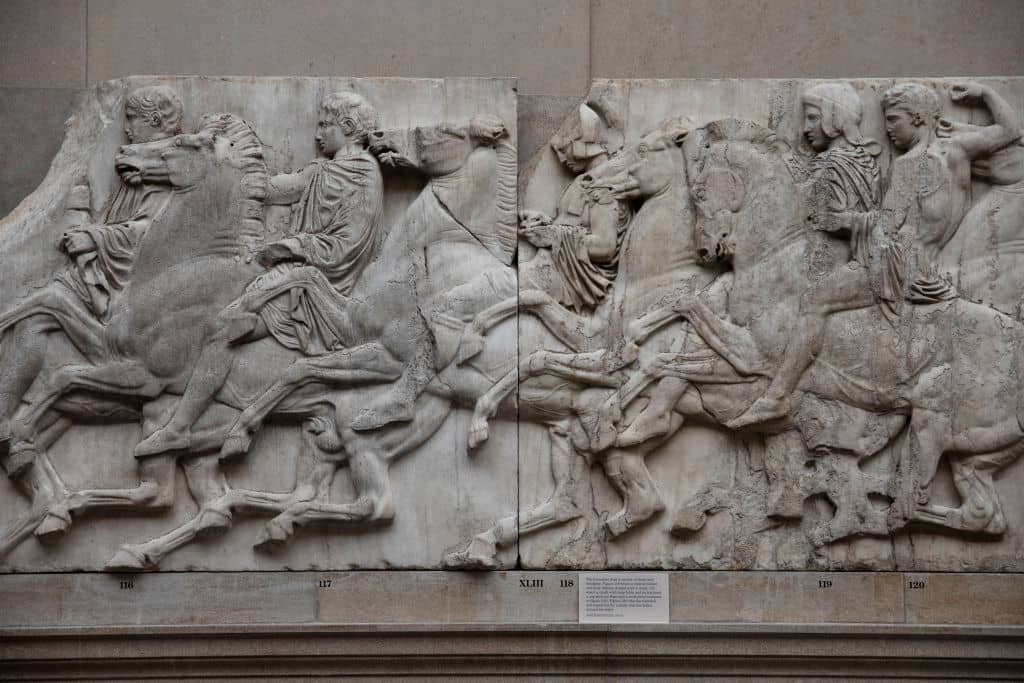

‘For the Greeks, it feels like a gaping wound,’ says Sarah Baxter, a columnist at the Sunday Times, of the Elgin Marbles. For 200 years, the Parthenon sculptures have taken pride of place at the British Museum. The Greeks want them back, but their pleas have fallen on deaf ears.

Greece’s prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis says he thinks Britain is edging closer to finally accepting that the marbles should be returned. ‘It will be a fantastic gesture, and that’s what I’ll tell (Liz Truss),’ he said of the return of the 2,500-year-old sculptures. But will he have any more success than his predecessors?

Lord Vaizey, former culture minister, thinks it is time to listen to Mitsotakis. Speaking at a Spectator fringe event at Tory party conference, he says it’s clear that the ‘moral case’ for their return is ‘absolutely unarguable’.

‘The Parthenon sculptures belong in the Parthenon…The logistical case (for their return) is also unanswerable: the museum in Greece is a world-class museum,’ he says.

But Lord Parkinson, former minister of arts, has sympathy with the British Museum’s position: that any country that wishes to borrow an object must accept that the museum owns the work.

‘Successive Greek governments have refused to consider borrowing or to acknowledge the Trustees’ ownership of the Parthenon sculptures in their care,’ the British Museum has said in a statement. ‘This has made any meaningful discussion on the issue virtually impossible.’

Parkinson says he fears this position – that the ‘stumbling block’ remains the position of the Greek government – is in danger of getting lost in this thorny debate. But for Sarah Baxter, the issue is rather simpler: ‘It would be extraordinary to see these marbles reunited,’ she says, pointing out that the separation of heads and arms from the same sculpture, thousands of miles apart, is in no one’s interest.

Vaizey agrees. He says it’s true that the British Museum ‘has, without doubt, cared for them for a long time’. Yet we shouldn’t pretend the museum has always taken the best care of them: ‘I don’t think we can pretend we are the best stewards,’ he says, pointing out an unfortunate incident in the 1930s, when the marbles were damaged by an overzealous cleaner. He also dismisses the claim that the sculptures were acquired legally: ‘In reality I think it was legalised theft by Lord Elgin,’ he says.

The Daily Telegraph’s Madeline Grant, who also spoke at the panel sponsored by the Parthenon Project, agrees that the objects should be returned, but perhaps not yet. ‘It is the moral thing to do,’ she says of their return. ‘It is hard to overstate the importance of the marbles to Greek culture,’ she points out. But we should be careful: the febrile times we live in, where debates such as this one often descend into culture war mud slinging, means there is a risk of a ‘slippery slope’ and the demand for other objects to be returned.

The Spectator’s James Forsyth, who hosted the panel, concludes the meeting by asking whether a compromise might be a solution. He recalls the Greek myth of Persephone and the pomegranate seeds. Having been tricked into eating food from the underworld, Persephone was forced to spend half her time in the underworld and half her time on earth. Could a similar middle ground be a way of out of this difficult debate?

Comments