I have seen the future of food. And some of you won’t like it. On a research trip to the Netherlands last week, along with the fellow partners of my firm, Bramble, I took a speedboat tour of the port of Rotterdam. One of the most awesome sights was the so-called ‘Innocent Blender’ – a vast smoothie-making fortress, box-shaped and silver – glinting over the water. This is where the British-based, Coca-Cola-owned company makes its ‘tasty little drinks’. The factory location makes sense: most of Europe’s imported fruit comes via Rotterdam. Massive tankers – 600ft long and filled with 40,000 tons of chilled orange juice from Brazil – move through constantly. The Blender is completely electric, runs on renewable energy and uses robots to purée, bottle and package. There isn’t anything wrong with this, even if it doesn’t quite chime with Innocent’s cutesy image. The global food system is stretched to capacity, struggling to cope with global instability and the extreme weather of climate change. As a species, we need to harness cutting-edge science if we are to feed ten billion people (the projected population of 2060), while also giving some land back to the ecosystems we’ve been chewing through for decades.

On our second day, we visited Wageningen University and Research – the epicentre of food system innovation. There we were shown a pill containing a miniaturised computer which, as it passes through your gut, sends live readings to your phone: temperature, acidity, location and transit time. The next model will take fluid samples at precise locations, providing a full readout of your microbiome. You then pass it in the usual fashion, give it a rinse – and hand it on to the next person.

Vertical farms, growing vegetables under LED lights, without sun or soil, are familiar. We witnessed a technique that goes further still: electro-agriculture grows plants without light, soil or carbon dioxide. The plant’s genes are edited to make it think it’s germinating underground. It is fed acetate at the roots, bypassing photosynthesis entirely. One person in the group looked stricken. ‘I’m an atheist,’ he said. ‘But I’ve just had a religious experience. Deep down, I’d rather grow food with nature than control it with technology.’ Science might prove his instincts right. We already know the gut microbiome is closely linked to our metabolism, immune system and mental health. What we don’t yet understand is how the complexity of soil life and the process of natural photosynthesis affects the micronutrients and microbiome of plants – and how that, in turn, shapes our health. Science has a way of solving one problem while quietly creating another.

Over dinner at my old Oxford college, St John’s, I sat between my old physics tutor, Sir Keith Burnett – now president of the Institute of Physics – and Sir Christopher Llewellyn Smith, the former director-general of Cern. They talked about how, at the highest level, even the sciences are a craft: your knowledge has to go so deep that it becomes almost a muscle memory, freeing up the brain to make new connections. Such craft can only be passed on through long-term, in-person apprenticeship. This, apparently, is why China won’t allow its leading physicists to work outside the country: they know that proximity matters. They want the world’s best apprentices to be Chinese.

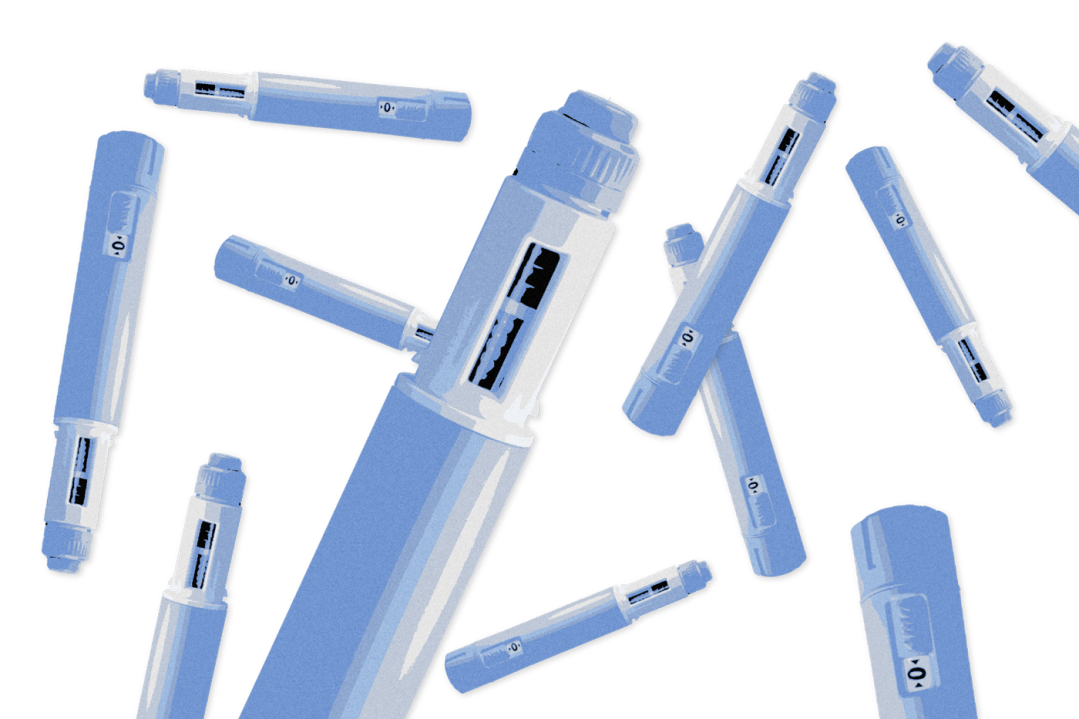

Last week Bramble hosted a breakfast for a group of ministers, scientists, food company CEOs and bosses of NGOs. The talk was about how to stop the NHS collapsing under the weight of diet-related illness. The CEOs know they are stuck. Unhealthy food is easier to sell, with bigger profit margins. If one company tries to shift to a healthier model, their profits just go to their competitors. Government legislation could level the playing field, but the politics of food regulation are hellish. Some policymakers hope the new generation of appetite-suppressing drugs, GLP-1 agonists such as Ozempic, will save us. But where should we draw the line? Obesity and its related diseases are rising in ever-younger age groups. Should we give children drugs with unknown long-term side effects because we have been too pusillanimous to protect them? ‘That,’ said a senior medic at our breakfast, ‘would seem to me to be a moral failing of our society.’

Possible side-effects aside, the surprise benefits of GLP-1 agonists add up. Early trials suggest that as well as helping with weight loss, they may improve blood pressure, cut heart disease, calm your mind, combat alcoholism and problem gambling, and curb sex addiction by reducing your libido. In other words, they can make you more attractive – slimmer and saner – but you won’t want to sleep with any of your new admirers.

Comments