My boy and I have fallen out. It happened like this. He decided to drive his newborn son, his partner and his partner’s three kids up to the Outer Hebrides, where his partner’s mother lives. The mother wanted to see the baby, and my boy and his partner were keen for her to see him. They wouldn’t all legally fit into my boy’s saloon car, so he tried to hire a seven-seater for the journey. But the car-hire companies won’t hire to the under-21s (even the under-25s have to fork out a whacking great premium) and my boy is 20.

Why not buy an old seven-seater for the trip? I said. If you aren’t worried about the state of the bodywork, I said, you might pick one up for less than it would cost to hire one for a week. The next day he rang to say he’d seen one advertised. He was stuck at work, he said. Would I go and look at it, and if £350 seemed reasonable, buy it and he’d pay me back.

To cut a long story short, the bloke selling the car was not a truthful man. He was a dealer for a start, not a private seller, as he’d stated in the advert. The history of his untruthfulness, I should have realised, was easily read in the breed of dog he had chosen to defend himself and his property — a Neapolitan mastiff and a pair of the biggest Dobermans I have ever seen. He swore on his baby’s life that the car was mechanically sound. But if I’d troubled to look at the colour of the oil on the end of the dipstick, I would have seen straight away that the head gasket was blown, or blowing, and I would have walked away and we’d all have lived happily ever after. Why I didn’t, I don’t know. It wasn’t until my boy had got the car home and seen the caramel colour of the oil that we realised we’d been shafted.

By a miracle, however, this clapped-out, failing vehicle not only got them all the way up to the Outer Hebrides, it also got them back again a week later: a round trip of nearly 2,000 miles. But it was the last kick of a dying horse. The very next day the engine overheated dramatically on the school run, and it was obvious that the car’s next outing would be to the scrapyard. But my boy had second thoughts. Rather than scrap the car, he said, he was going to put it in the local car auction — where cars are sold as seen, and mug punters abound — and try to recoup his losses. And his readiness to put this worthless old trap in the auction became a bone of contention between us.

I’ve been a very broadminded, easy-going father to my boy. I can’t remember once clashing with him about anything as purely abstract as right and wrong. He was born with a healthy conscience and I haven’t felt like meddling. (Come to think of it, if anyone has played the moral arbiter in our relationship, it’s been him.) But for once I felt strongly enough about something to speak up.

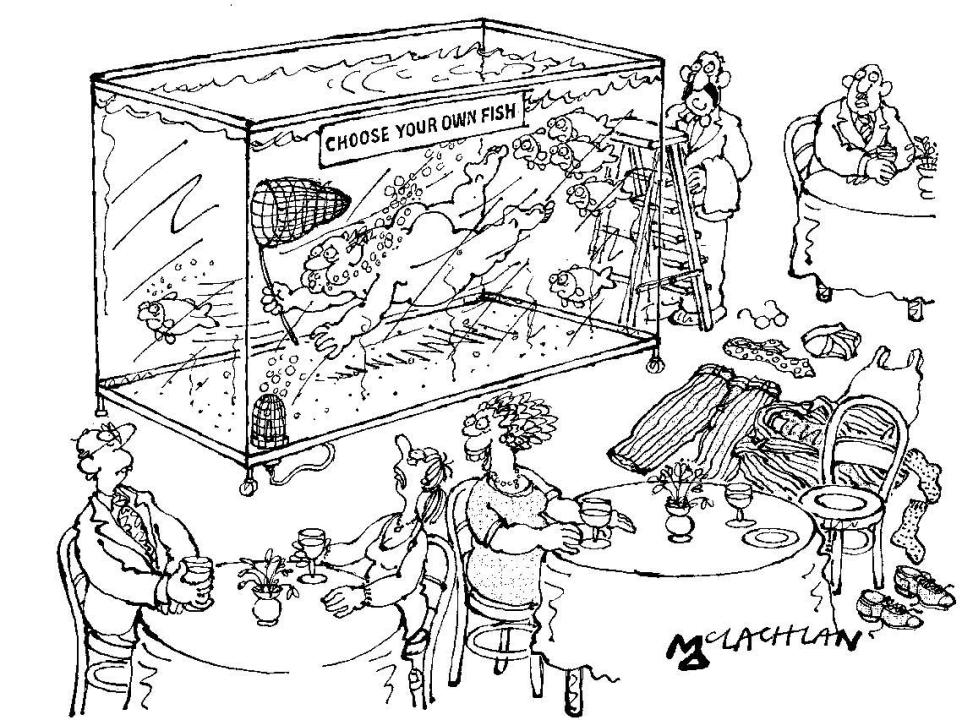

I knew, I said, and he knew exactly who would bid and end up buying rubbish like that. It wouldn’t be one of the savvy, cold-hearted dealers. It wouldn’t be one of the bums, loungers, dreamers or idlers. It would be one of the poor families hunting among the rows of jalopies, hoping to find the bargain that will transform their lives. We’ve seen them, I reminded him. Father, mother and the two kids. They are malnourished, cheaply dressed, united. Their faces are torn between hope and anxiety, especially father’s, for he doesn’t know much about cars, and they’ve been scrimping for months.

And we’ve watched them, my boy and I, after the auction, approaching the mechanical failure on which they’ve gambled their cash. The dad solemn with anxiety; the eldest boy solemn because his father, whom he reveres, is solemn. The family hangs back, spectating, while father bravely fiddles the key into the lock. We’ve seen it, I reminded him, and we’ve been there. I’ve been that wretched dad, and he has been that attentive, anxious son.

For the first time in his life, I told my boy he was in the wrong. I might even have mentioned the phrase ‘common decency’. ‘You know what your trouble is?’ he said. ‘You’re too nice.’ And that was that. He put the car in the auction. Neither of us went, so we didn’t see who bought it. It made £250. My boy was slightly disappointed, he told me (with an unmistakable note of triumph in his voice), that it hadn’t made more.

Comments