Q: ‘How would you define transcendence?’

A: ‘Well, how would you define it?’

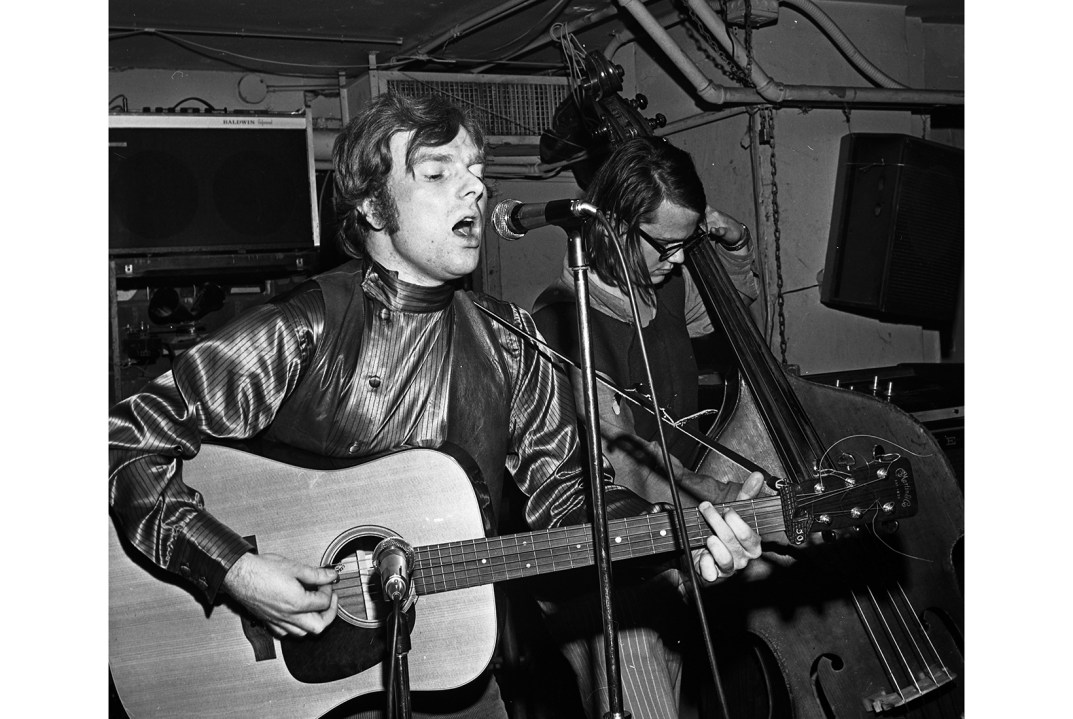

I interviewed Van Morrison last year. (I’m fine now, thanks.) While the exercise wasn’t quite the near-death experience of industry legend — he was polite and accommodating, if not always exactly forthcoming — it got sticky at times, as the above exchange illustrates. Let’s call it a solid 6.5 on the Lou Reed Scale.

Morrison, who turns 75 on the last day of this month, was formed in an age when a people-pleasing public persona wasn’t essential for musical success. In rare interviews, he engages with informed questions about music but refuses to indulge in the game most journalists insist on playing, which is to map the lyrical concerns to the lived life. Sniff around his personal motivations and he balls up like a hedgehog being poked with a garden rake.

Sniff around his personal motivations and he balls up like a hedgehog being poked with a garden rake

In song, Morrison has interrogated Rosicrucianism, spiritual rebirth, the ache of place, the struggle to write, loss of innocence, as well as the joys of potted herring, window cleaning, Max Wall and Lester Piggott. He has adapted the work of Yeats, Blake, Paul Durcan and Peter Handke, been inspired by writers as diverse as Alice Bailey, Lord Byron and Alan Watts, and thanked L. Ron Hubbard on an album sleeve. In 1983, he wrote a song called ‘Rave On, John Donne’. There is ample evidence of a hefty and esoteric hinterland. Yet in interviews he repeatedly insists that these subjects are merely randomly selected aids, impersonal writing prompts.

It’s a disingenuous tactic designed to discourage private inquisition. And fair enough. Arguably no other artist has better expressed through music what Morrison once called the inarticulate speech of the heart. It seems a tad unjust to expect him to talk fluently about it.

I like this spikiness, because it keeps Morrison near the margins, where I always feel he belongs. It irks me that these days he presents as a rather orthodox entertainer, though it’s partly his own fault. He’s long been operating on cruise control, taking on the role of the stoic soul man, squeezed inside a suit, features obscured beneath a pork pie hat and bus driver’s shades, barking out an overly polite blend of blues and jazz. His more recent albums and live performances, while never exactly perfunctory, lack the high-wire sense of jeopardy and questing spirit of Morrison in his pomp.

And while I’m as happy to hear ‘Brown Eyed Girl’, ‘Moondance’ and ‘Have I Told You Lately’ as the next Radio 2 listener, these mainstream mainstays barely hint at his wild vision. To me, Morrison will always be thrillingly sui generis, an eternal outsider, eccentric, confrontational, almost avant-garde in his vaulting determination to give unfiltered vent to whatever’s bubbling away inside. His greatest records — Astral Weeks, Veedon Fleece, Into the Music, Common One — are transcendent, extemporary, uncompromising, unique, poetic and truly experimental. Both beautiful and brilliantly odd.

Like Kate Bush, Morrison has never been afraid to appear deeply silly in the service of the muse. Most short, spherical Belfast boys would baulk at declaring their intention to ‘put on my hot pants/ And promenade down funky Broadway/ ’Til the cows come home’. Not Van. If he’s feeling it, he’s singing it, usually with outrageously idiosyncratic vocal phrasing. He blows bubbles for two minutes at the end of ‘Tupelo Honey’, wheezes like a consumptive monk for the bulk of ‘When Heart Is Open’.

He told me last year that he ‘acted his way’ through his songs on stage. Having seen him perform on countless occasions, from Glastonbury to Glasgow, I don’t believe it for a second. I’ve watched him hold an audience in pin-drop stillness with nothing more than a series of whispers, grunts and exhalations. I’ve seen him rise from silence to lion’s roar, the vocal equivalent of a Porsche going from nought to 60 in three seconds. When Morrison is tuned in, he loses all sense of himself. Witness his magnificent exit from the stage in The Band’s 1978 concert film, The Last Waltz, wearing a sparkly purple jumpsuit and high kicking like a drunken chorus girl. No wonder he can’t talk about it.

Sightings of this version of Van have become increasingly scarce. His most recent album, Three Chords & the Truth, is strong but unspectacular. His last masterpiece — No Guru, No Method, No Teacher — landed in 1986. Yet the late-period resurgence of David Bowie, Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen gives hope that Morrison might also conjure a final burst of brilliance. The voice is still there. The flesh appears willing. At 75, there’s time yet for him to shuck off the hat and shades — the armour — for one more dive into the mystic.

Van Morrison is touring Britain this autumn with live shows at Newcastle Racecourse, Electric Ballroom and the London Palladium.

Comments