The fashion for museum-quality exhibitions in commercial galleries continues apace with two notable shows in Mayfair: Cy Twombly at Eykyn Maclean, and Julio González at Ordovas. Both galleries specialise in this kind of display, which must be more to do with impressing potential clients than with generating income, given that both are loan shows. I hope there’s also an altruistic motive here, however slight: to provide another forum for the public to view high-quality art they might not see elsewhere. Certainly these venues offer a new and welcome resource to the London gallery-goer, and should be better known.

Chistopher Eykyn and Nicholas Maclean, who both have many years of experience at Christie’s, deal in key Impressionist and 20th-century European and American artists. They already have a New York gallery, which is the destination of their Twombly show when it closes here after launching their new London gallery. Pilar Ordovas is another Christie’s-trained specialist dealer, who opened a gallery last year with an impressive exhibition of Bacon and Rembrandt.

Eykyn Maclean’s excellent Twombly show (30 St George Street, W1, until 17 March) is loaned from the Sonnabend Collection, which accounts for its focus and quality. Ileana Sonnabend (1914–2007) was an influential dealer and collector, the woman who requested a Matisse instead of an engagement ring when she consented to be Leo Castelli’s wife. She met Twombly through Rauschenberg and began to acquire his pictures with unerring skill. All 11 works in this show are both interesting and domestic-sized. (Most of the Twomblys one sees are huge.) All employ the characteristic swirling or angular scribble for which he was celebrated, some to better effect than others. ‘Triumph of Galatea’ of 1961, for instance, is rather florid, whereas ‘Untitled (New York City)’ of 1956 is altogether more painterly and mesmerising.

My favourite is a small oil, crayon and graphite on paper, laid down on canvas, from 1962 called simply ‘Roma’. Why is it so pleasing? Looked at in one way, it’s only a bit of scribble, differently angled, a rough chimney-shape in blue crayon with five dabs of pink oil paint, and three further tiny touches of pink. Yet it is magical and poignant, partly because of the bit of edge-work on the right, which might almost be an afterthought, but is actually essential to the success of the whole. It is this gift for perfect placing — perfect phrasing — that sets Twombly above so many ordinary abstract painters. ‘I’m not an abstractionist completely,’ he said in 2007. ‘There has to be a history behind the thought.’ That doubtless helps, but perfect pitch does as well.

Julio González: First Master of the Torch at Ordovas (25 Savile Row, W1, until 2 April) basically consists of only four metal sculptures: one each by González, Eduardo Chillida, David Smith and Anthony Caro. For me, the show is stolen by the two upright forms of Chillida and Smith, of which ‘The Woman Bandit’, in cast iron, bronze and steel, by Smith, is the finest. The woman, with green bronze belly over a skirt like a partly furled parasol, stands proud and declarative as a Hemingway sentence. Chillida’s welded iron ‘Oyarak I’ has a more utilitarian poetry to it, referencing the farrier and the waterworks. Caro’s welded steel sculpture is like a frog on a dissecting table. Only González’s piece, ‘Tête aux grands yeux’, in welded iron, which is good but doesn’t have the dramatic punch of the others, lets the side down.

González, the first sculptor to use welded metal in a modern way, imparted his skills to Picasso, after which they fell out. This exhibition is intended to show González in dialogue with Picasso, Smith, Chillida and Caro, but Picasso is only represented by a photograph of his studio, and there’s not enough of González’s own work to reintroduce him to a public which might be unfamiliar with him. (Some of his works have been held up by the Spanish temporary export committee.) Three drawings in the back room supplement the single sculpture, but don’t add a great deal. After the impressive début of Bacon and Rembrandt, this new show at Ordovas is something of a disappointment, though the Smith and Chillida sculptures are worth making a detour for.

Wladyslaw Mirecki (born 1956) is a painter of the East Anglian landscape where he was born. He works exclusively in watercolour, with a painstakingly detailed technique which manages never to look stilted or dead. Self-taught, he makes his own rules, which is perhaps why there is so much vitality to his work. He is particularly good at capturing the uneasy alliance between the natural and the man-made: a telegraph pole and its web of wires, behind the tangled thicket of an untrimmed winter hedge set against snow; or the stately arched length of a viaduct against river or fields. Mirecki can paint an old tree on a bank surrounded by falling leaves, without descending into Pre-Raphaelite sentiment or neurosis, and even make large expanses of grass look interesting. An exhibition of his new work, entitled Closely Observed Landscape – East Anglia and Beyond, is currently showing at Piers Feetham Gallery (475 Fulham Road, SW6, until 24 March), and deserves your attention. He is varying his usual subjects of Colne Valley and environs with figure paintings and sea studies. Among the many beautiful images, look out for ‘Bluebells in Chalkney Wood’.

A very different stretch of England is celebrated in Alex Lowery’s new show, Light Industrial, at Art Space (21 Eastcastle Street, W1, until 23 March). Lowery (born 1957) paints West Bay, near Bridport on the Dorset Coast, and the Isle of Portland, some 20 miles away. He has made more than 200 paintings of West Bay, distilling a language of abstracted form from the observed elements of vernacular seaside architecture and coastal defences. West Bay is clearly an image bank for him, but he’s been painting it long enough for changes to occur in its compositional limits — for instance, as the shape of the harbour has altered through redevelopment.

Portland is a more recent site of Lowery’s scrutiny, but produces some of the most enjoyable paintings in his new exhibition. For me the essence of his work resides in the slightly mysterious building-block geometries of the coastal hangars, and their fields of flat, abstracted colour. Lowery is currently using more colour, and particularly a subtly modulated pinky-mauve, which I find most seductive. There seems no end to the possibilities.

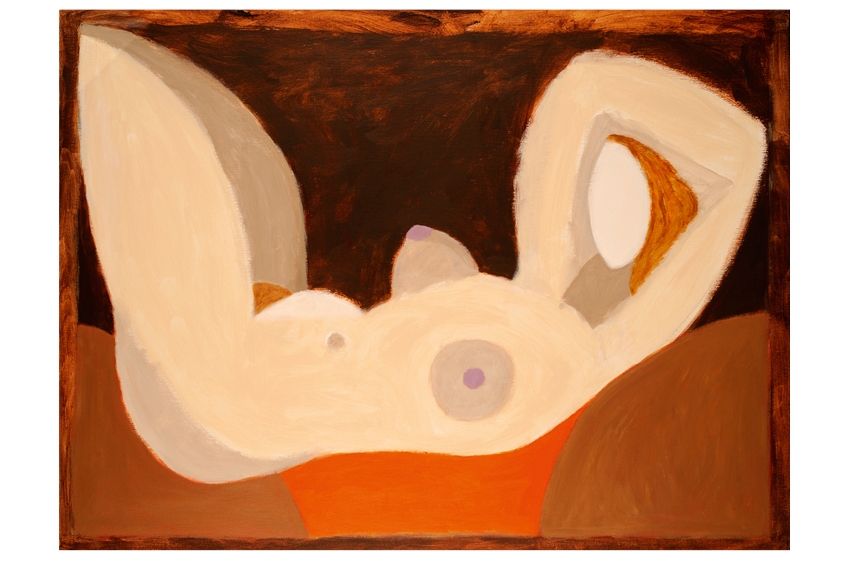

Down in Cornwall, at the Newlyn Art Gallery (until 28 April), is a retrospective exhibition of the varied works of Breon O’Casey (1928–2011). Son of the playwright Sean O’Casey, Breon gravitated to St Ives in 1959 when it was one of the centres of modern art in Britain, moving to nearby Paul in 1975. He worked for the sculptors Denis Mitchell and Barbara Hepworth, painted for himself and made jewellery to support his family through difficult times. In essence a still-life painter with rather too great a debt to Braque, he worked on a repertoire of circles, triangles, birds, fish and nudes, with extended excursions into weaving, printmaking and sculpture. That he was aware of the pitfalls of a superficial lyricism is evident from his remark: ‘To make a picture sing is difficult. To make it talk is far and away harder.’ Quite.

Comments