Numerous civil servants have recalled their first encounter with Labour ministers following their election victory last year. After the new rulers of Britain first walked into their departments, and following pleasantries with their officials, ministers asked them for their ideas about how to run the country, to which the confused officials responded: ‘That’s your job, minister’.

The new government was woefully underprepared, and in opposition did little in the way of thrashing out policy

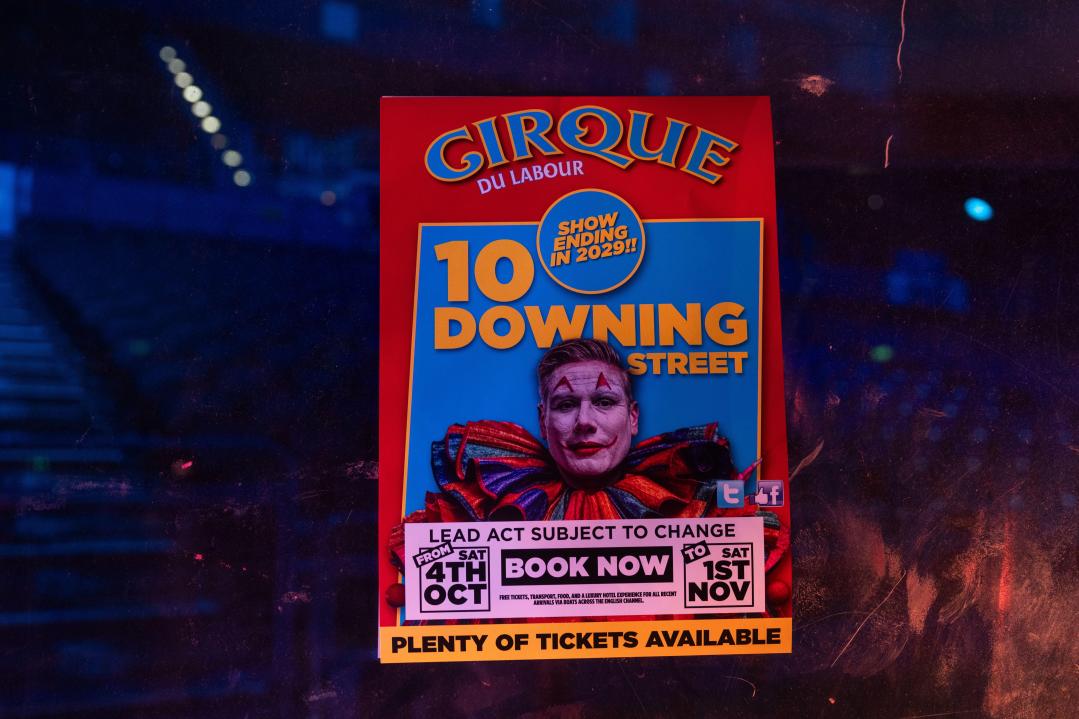

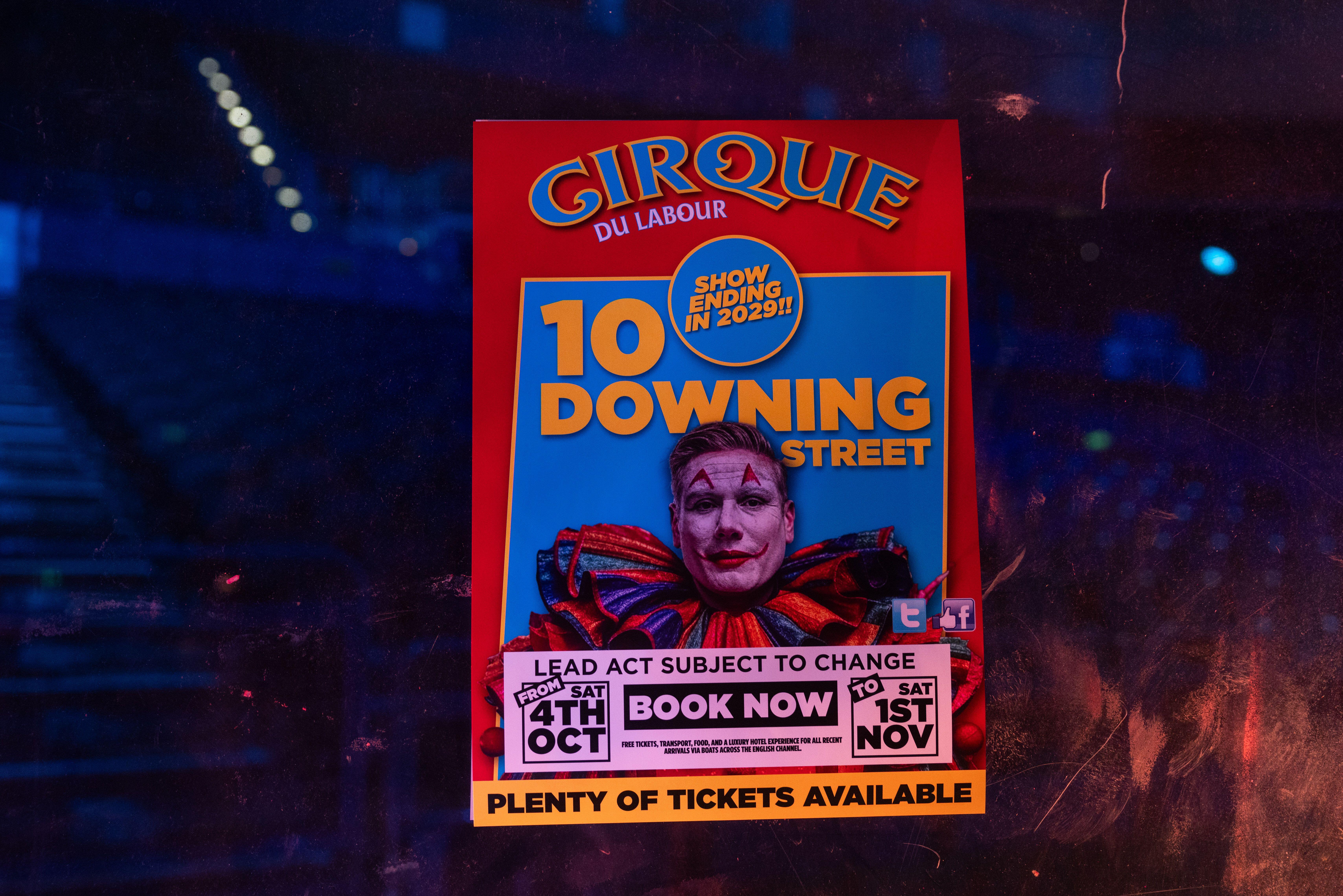

It’s a tale repeated by various people in SW1, and might help to explain the surprising implosion of the Labour government so soon after their landslide victory. Eighteen months on, Labour are now polling in the teens, and Keir Starmer is the least popular prime minister in history, while Rachel Reeves has the lowest satisfaction rating of any Chancellor of the Exchequer since records began in 1976. Things are so bad that the bookies strongly favour Starmer resigning by the end of next year.

In a sense this is just part of modern politics, since all governments are unpopular now, but the present British regime has proven a standout failure nonetheless. They have some way to go before equalling Peruvian president Dina Boluarte’s approval rating of 2 per cent, but don’t count them out just yet.

There are different types of failure; a government might immiserate a country, and build problems that can last a generation, yet still be politically successful, ensuring that enough voters are rewarded to win elections. This is successful politics – it’s what braying Right-wingers like me expected from Labour, fearing that they would do enough to bribe and flatter the coalition of the ascendent to ensure electoral success. Luckily, I was too pessimistic, and things are even worse than I expected.

Much of this failure must be down to the character of the Prime Minister himself, a man who notably fails to inspire. Starmer’s life story should be interesting, heroic even: he actually had a career before politics, as a celebrated human rights lawyer, to the extent that it was rumoured that Bridget Jones’s love interest Mark Darcy was based on him (which, sadly, was not true). He plays the flute, which is quite interesting – as does the Chancellor, in fact – but there doesn’t seem to be much more to him, and he famously has no favourite novel or poem, no phobias or dreams.

People complain about career politicians but we now have a non-career politician at the helm and he has proven inadequate at many of the most basic tasks of running a government. He’s notably bad at managing MPs, many of whom feel that they are taken for granted, hasn’t even met some of them, and apparently doesn’t remember their names – something which Tony Blair was famously skilled at. (If you suffer the same problem, and I do, Blair would apparently use someone’s name three or four times early on in a conversation, and it always stuck.)

If Starmer does feel contempt for his MPs, there is indeed a serious problem with getting talented people into politics, which has seen a notable decline in the quality of elected representatives. While government ministers have been found taking all sorts of freebies, the obvious solution – that fewer politicians should be paid more – is totally at odds with the public mood.

This lack of talent was probably aggravated by the Corbyn years, as a result of which more competent Labour activists stayed in private sector jobs rather than becoming MPs. This left them with a parliamentary party dominated by people from trade unions, local government and charities, the latter comprising one-third of all new Members of Parliament.

The charitable sector has many qualities, but charities are also incentivised to ignore the problem of second-order effects, or at least be ideologically blind to them. A government of charity administrators will inevitably create a system filled with moral hazard and perverse incentives, because their continued existence depends on downplaying them.

There is a deeper problem that the centre-left is out of ideas

British politics has also become more chaotic, and Labour faces the same problem as David Cameron’s government, of being squeezed on both the Left and Right. They are losing young graduates to the Greens but, more disastrous in raw electoral terms, Britain’s fast-growing Muslim population has become demographically assertive enough to form their own political movement, unfortunately on Starmer’s watch. Labour MPs are literally scared of their own former supporters, and to make matters worse, they cannot admit to this fear because it would prove their opponents correct; the psychological impact must be huge.

Many of these new MPs would have spent their lives expressing popular opinions, and now find themselves in a position where they have to do some very unpopular but necessary things. This fear of unpopularity drove Labour’s failure to cut £5 billion from the welfare budget in June, due to backbench unrest, with Janan Ganesh calling this ‘retreat’ the ‘central event of the government so far…It established the precedent that backbenchers and grassroots can morally blackmail him.’

The previous Labour government came into office with the blessing of a strong economy, which enabled them to raise welfare spending while allowing the free market to get on with producing wealth. Starmer has not had that luxury, and it is for this reason that Ganesh predicted their unpopularity back in April 2024, forecasting correctly that the new government would be hated in no time.

‘Labour exists to spend money,’ he wrote: ‘No disgrace there: it is the quickest route to some of its social objectives. But with taxes and public debt so much higher than when Labour last governed, the pain this time will be sharper. Here is a prediction. After some initial fiscal restraint, Labour, in frustration, will borrow more – on past evidence, much more – than markets currently expect. If taxes rise, too, the public’s reaction won’t be the kind of grudging assent granted to Gordon Brown’s penny on national insurance in 2002.’

The idea that the rich can be squeezed further is always attractive, but contradicted by the fact that we already heavily reliant on high earners, and at some point welfare cuts will have to come if we want to continue borrowing money – but even modest inroads have so far proven too much for Labour backbenchers.

Aside from Ganesh, there was otherwise a notable absence of media scrutiny about the incoming government. Many journalists assumed that they couldn’t be worse than the current lot, and were just pleased that Corbyn had gone. But there was also a widespread belief that much of the chaos of the last government stemmed from conflict between the Tories and the civil service, and that under the new regime they would work in tandem. Some technocratic, and ideologically agreeable, solutions would be found to the multiple crises now facing the country. In line with this thinking, they appointed former civil servant Sue Gray, a decision which soon imploded, eroding Starmer’s authority from the start.

To add to this, all these problems have probably been aggravated by the arrival of smartphones, which make it much harder to run the country because everyone, MPs and journalists included, is easily distracted and searching for more news and drama.

The media may not have scrutinised them enough, but as Will Dunn observed in the New Statesman, hedge funds did, commissioning research on the next government. The results were not promising.

‘The fund wanted to know who Labour’s MPs and ministers would be, what policies they would have, and how effectively they would deploy them. The polls said Labour was heading for a landslide victory and a huge majority. The research, according to a person familiar with the report, said, “There is no plan, there is no vision, and they’re not going to succeed because they don’t have the talent.” The fund decided to take a short position on UK gilts, effectively betting that Britain’s borrowing costs would rise. They made a lot of money on that bet.

Many journalists assumed that they couldn’t be worse than the current lot, and were just pleased that Corbyn had gone

‘The Labour MPs’ rebellion over the government’s welfare bill in July was further evidence for the market. “When you’ve got a 168 majority and you can’t get through some welfare spending cuts,” one City strategist told me, “the markets have concluded… there’s not a cat in hell’s chance of bringing the fiscal side back.” They pointed to the UK’s £1.4 trillion in public-sector pensions liabilities and the “explosion in disability benefits for the under thirties” as factors that would prevent investors from buying Britain’s debt. “The bond vigilantes aren’t stupid,” they told me. “They’re looking at this and saying, ‘If your 405 MPs aren’t willing to tackle this… then there’s no hope for you.’”

The new government was indeed woefully underprepared, and in opposition did little in the way of thrashing out policy. This may have been by design, because having these conversations would leave them vulnerable to attacks by the Left, causing division and negative headlines, and many were scarred by the rancour of the Corbyn years.

But perhaps there is a deeper problem that the centre-left is out of ideas, or at least none that don’t require Blair-era growth. In contrast, the radical left is full of ideas – degrowth, climate activism, citizens assemblies, decolonisation, rent control. Whether they actually work or not is another matter.

While Starmer was viewed by commentators as a technocrat who would rule sensibly after a chaotic succession of Tory governments, then, as Ganesh has also pointed out, you can be boring and bad. In fact his lack of hinterland is surely part of the problem – he doesn’t seem to have any vision of the country or what he wants to change, and his tweets in particular feel like the empty slogans of a dying consensus.

Starmer’s core belief, if there is one, is in a system of human rights enshrined by the post-1997 constitution, and the idea that decision-making should be moved away from democratic bodies towards various units, councils and other unelected institutions, both national and international, which take account of rights, needs and principles of equality and fairness.

None of these core beliefs offer a solution to the multiple problems facing the country, whether it’s poor growth, an inability to build, illegal immigration or badly performing public services – indeed, they are frequently a stumbling block to the proposed solutions, making them either illegal or ruinously expensive. A consensus dies when a vanguard of intellectuals come to see that no improvement will come until comfortable assumptions are discarded, and the previously unthinkable is the only available alternative. The country is on the cusp of such a psychological leap, but it requires a statesman with vision. Someone who can dream.

This article originally appeared on Ed West’s Wrong Side of History

Comments