This is an account of the multiplicity of ways in which men ‘stole back time from their captors through creativity’ in the prisoner-of-war camps of Europe and the Far East.

This is an account of the multiplicity of ways in which men ‘stole back time from their captors through creativity’ in the prisoner-of-war camps of Europe and the Far East. It is not about the escapers, but about the men who ‘turned the contents of a Red Cross parcel into a cooking stove, a barometer or a stage set; men who discovered a talent for painting or foreign languages, or who took exams that might help their careers when they got home’; about elaborate sporting fixtures and concerts and theatrical productions and the near-miraculous saving of lives on makeshift jungle operating tables; about ‘mental escape’ through study, gardening or birdwatching (‘captivity was in many ways the ideal setting for the keen ornithologist’), and the ‘uplifting power of genuine art and artistry’ when the chips are down.

However, Midge Gillies is a woman who cannot resist a good story; she includes prisoners’ accounts of their own capture, and stories of heroic and all too frequently tragic adventures which take their place as a counterpoint to the POWs’ efforts to create some sort of imitation of normal life — touchingly reminiscent at times of children playing house.

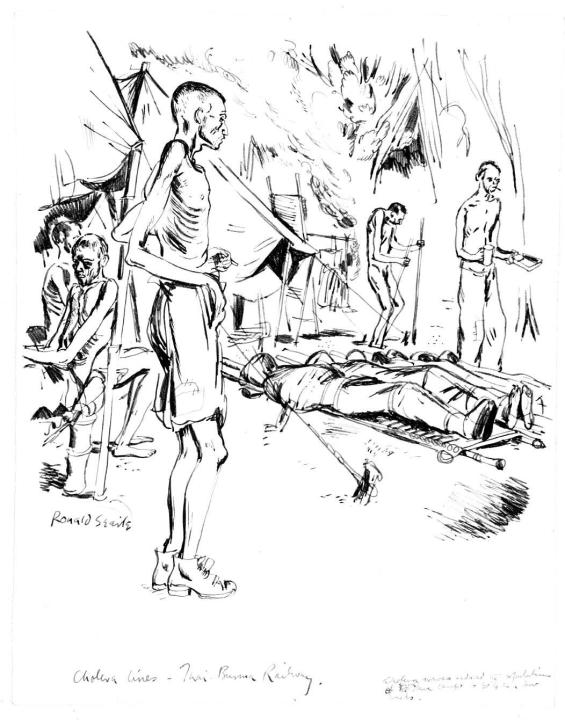

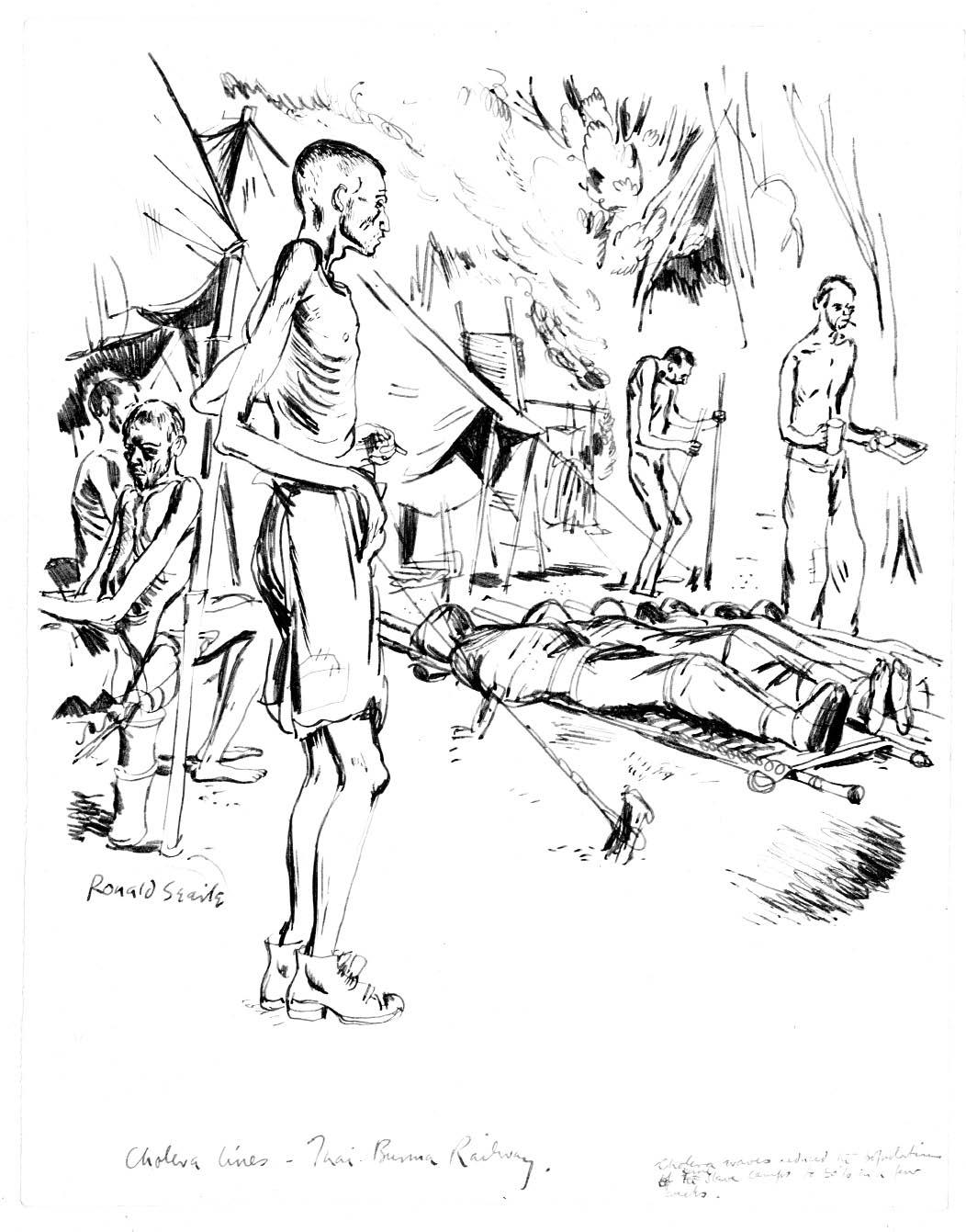

It is a necessary counterpoint, too, because these astonishing tales of improvisation, ingenuity and courage are so enthralling, and also so comforting in their suggestions of camaraderie and the essential goodness of human nature in a tight spot, that it is all too easy to forget the accompanying brutality and indignity. We have the testament of the survivors, the toughest, not the many who for reasons of luck or a lack of physical or spiritual stamina succumbed to starvation, disease or despair or emerged with their spirits permanently broken.

The book is a memorial to the author’s father, who was a POW in Germany, and her affectionate observations of the effect the experience had on him are woven unobtrusively into the narrative. She identifies ‘indefatigable optimism’ as the vital element of his survival strategy. The Barbed-Wire University is compiled from personal narratives put into context with an appropriate amount of military history, several maps, and a judicious use of statistics which provide a constant corrective to complacency

Gillies refers to the ‘hierarchy of POW suffering’. Because of distance from home, climate, diet, tropical diseases and slave-labour, incarceration was immeasurably worse in the Far East. The Germans felt ‘a cultural connection’ with their British prisoners which they did not feel for the Russians; the Japanese had no respect for soldiers who allowed themselves to be captured, and treated their prisoners accordingly.

Every facet of this epic story is covered with sensitivity, restraint, notable fairness (in dealing with such delicate matters as the disparity of conditions between officers and men, for example), and a leavening of humour; Gillies wonders gently what sort of reception Frank Bell got when, at death’s door from diptheria, beriberi and ulcers, he finds the strength somehow to lecture his fellow patients on Pascal from his hospital bed.

The book is full of unforgettable stories: of the imaginative thoughtfulness of the packers of Red Cross parcels, and of Miss Ethel Hardman, Director of the Educational Books Section, who was regarded by POWs as ‘a sort of distant but kindly aunt’; of the young Dutchman on his way to the East Indies who loses his virginity at sea to a French archeologist called Madeleine, and is taught to read hieroglyphics and set the task of finding her another ‘Tartar stone’ — inspiring heroic feats of archeological excavation along the Burma Railway.

There is the writer H.M. Belgion who corresponds with T.S. Eliot, Jonathan Cape and C.S. Lewis, receives hampers from Harrods and antiquarian books from Paris and writes a bestseller called Reading for Profit; the anatomy lecturer who uses the emaciated bodies of fellow- prisoners as diagrams (‘you could see everything’); the man who discovers a complete set of the works of George Bernard Shaw when ordered to mend the beds in a Japanese brothel; and the old Chinese lady who appears with ‘a cardboard box packed with delicate porcelain cups, each containing a small sponge cake’ for a POW work-party, and despite a terrible beating from the guards returns with her cakes the next day, undaunted. Such stories illuminate a great subject in engrossing detail.

Comments