I think it was a Frenchman — it usually is — who observed that the English love their animals more than their children. At first glance, General Jack Seely’s Warrior: The Amazing Story of a Real War Horse — originally published as My Horse Warrior in 1934 — is striking proof of this. In an entire book devoted to the exploits of his horse, the author’s final mention of his son Frank is stunning in its brevity:

We had a last gallop together along the sands, Warrior and [Frank’s charger] Akbar racing each other; then I drove him in a motor-car to rejoin his regiment .… He asked me to take care of Akbar, and I replied that Warrior would take care of that. He was killed not long afterwards while leading his company.

I don’t believe that the General — Lord Mottistone as he became, Minister for War as he had been — was quite as inhumane as this might indicate. In fact, I think there is a vast well of emotion under those words which, when read properly, can bring a choke to the throat. However, what is so very English is his feeling that it is fine to express emotion about animals, but to do so about our fellow men is much more questionable. To say that this is psychologically and ethically limiting is to understate. Witness its reductio ad absurdum: the self-serving, tasteless mawkishness of the ‘Animals in War’ memorial. Who among the living does it move? Certainly not the animals. And who among the dead would it have comforted? Being remembered is no consolation to those with no conception of time.

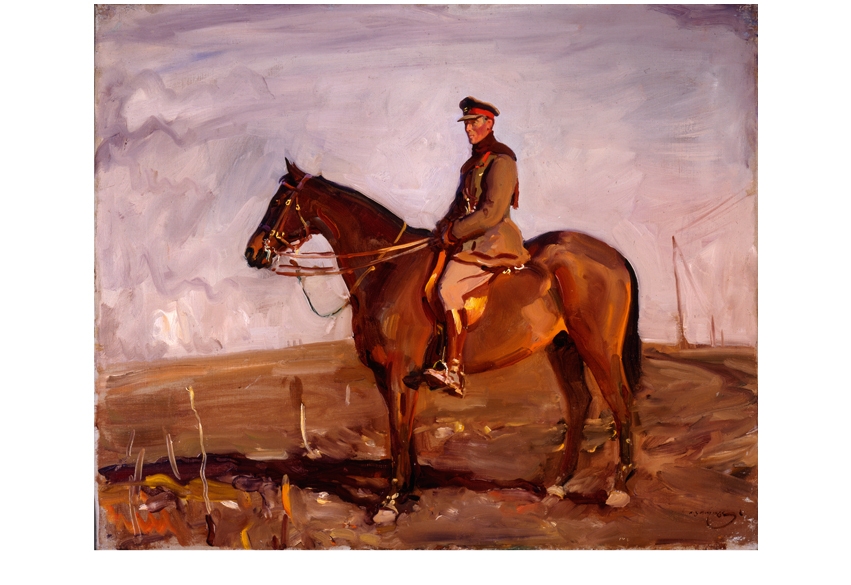

However, as I have already said, Seely’s version of it, the old-fashioned version, has more to it than this. The book is indeed the story of one thoroughbred, from birth in 1908 on the Isle of Wight, through the horrors of cavalry charges at machine guns and the deprivations of the trenches, to winning the Isle of Wight point-to-point in 1919 and a retirement of fox-hunting and rural comfort (Warrior died in 1941, aged almost 33). However, as men and other horses fall like ninepins around Seely and his mount, you get the feeling that through the horse the General is actually telling the reader — and perhaps himself — that something came through the horrors of that terrible conflagration in one piece; that something of worth remained.

On the same day that I read Warrior, for contrast, I went to see the film adaptation of Michael Morpurgo’s children’s novel War Horse. I did not hate it as much as I thought I would, because, despite being overblown, overscored and overlit, Steven Spielberg cannot help but create striking scenes, and some of the actors — Hiddleston, Cumberbatch, Kennedy — are also superb. I would even suggest that the images it supplied me with allowed me to make more of Seely’s rather spare prose. However, I was also aware that War Horse is very much the child of Warrior, and there can be no denying the superior charm, and gallantry, of the sire over his progeny.

Comments