Paula Rego had a retrospective at Tate Liverpool a decade ago and a big show in her native Portugal, where she is properly regarded as the country’s greatest living artist, but both exhibitions seem niggardly in comparison with the more than 200 works shown in some 14 rooms at the Reina Sofia in Madrid. Even to someone who has made a close study of her work, this is a revelatory, even overpowering, display of both her versatility and her passion. The exhibition has been curated by Marco Livingstone who, in his elaborate catalogue, includes as well as his own lucid introduction, refreshingly free of artspeak, a fascinating interview with the artist. Rego says of the ever-present threads in her oeuvre: ‘I think bullying and revenge run all the way through. Bullying people taking advantage of other people. The overdog and the underdog …[My] childhood in Portugal is also very important …power games, or whatever you’d call it. I think there has always been a sort of exuberance …that has something to do with sexuality.’

Given these views it is both remarkable, and entirely understandable, that she has risen to her well-deserved success as an exclusively narrative artist. Rarely has that awful cliché that every picture tells a story been so apt. The majority of her stories are deeply subversive, as befits someone whose childhood was dominated by parents and aunts who vied with each other to tell her the creepiest and scariest stories. But, Rego being Rego, the most innocent of stories, from nursery rhymes to Peter Pan, emerge laden not with sinister undertones but with frequently shocking overtones.

One of the bonuses of the Madrid show is the selection of early paintings and drawings dating from the 1950s when she was barely in her twenties. Some artists, such as Picasso, constantly change their styles, while other sail serenely through life endlessly repeating themselves. Rego manages, with extreme sophistication, to change her style — and her media — while being entirely consistent in her narrative power. ‘Celebration’ (1953) is a wonderful, satirical account of a drunken birthday party where the celebrants, in various states of somnolence and incoherence, with their mask-like faces reminiscent of James Ensor, are clearly the ancestors of the lithographs she published this year to illustrate a short story by the Portuguese writer João de Melo entitled O Vinho (Wine). An even earlier work, a quite savage, heavy black pencil drawing of 1952, ‘Dog Woman’, re-emerges in the ‘Dog Women’ series of paintings in the mid-1990s, an unforgettable example of reverse anthropomorphism.

Rego’s idol is Goya and you can see his fiercely political approach in the 1960, satisfyingly shocking ‘Salazar Vomiting the Homeland’, a singularly brave work, now owned by the Gulbenkian Foundation, but painted while the dictator of Portugal, who made Franco look like a true democrat, still had another eight years in power. Even Gillray attacking George III seems positively mild in comparison.

Sometimes Rego’s gallows humour gives way to pure rage, as in her paintings and etchings devoted to abortion, partly inspired by Portugal’s repressive abortion laws and, worse still, the possibly clerically induced apathy of the Portuguese population. They failed to turn out in the referendum on the topic thus effectively producing a negative vote.

Technically Rego is also interesting in that she switched from oil to acrylic and many of her best later paintings are in pastel. This is in part because she reveres drawing and constantly practises it, and partly because, as in drawing with pencil or pen, the pastel instrument she uses is itself the medium, making a more direct human contact with the surface than a brush loaded with paint. Thus her huge pastel paintings, often as big as 180 x 120 cms, are as subtly executed as a Degas while having the initial, visceral impact of the Black Paintings of Goya.

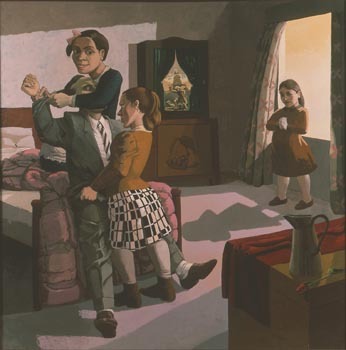

Above all the avid consumer of stories is herself a great storyteller and nowhere is this truer than in the magnificent paintings based on Martin McDonagh’s play The Pillowman, itself a compelling, dramatically overpowering inquiry into the nature of truth and fiction, the identity of the storyteller and the verification of the tale. McDonagh’s stories in the play take root but, like the words of any play, they can evaporate from mind and memory. Rego’s visual reworking of McDonagh’s stories cannot, once seen, easily be erased and, executed in 2004–5, hold their own with her classics of the late-Eighties such as ‘The Family’, ‘The Maids’, ‘The Policeman’s Daughter’, etc.

Great exhibitions like this are usually only put on soon after an artist’s death. Happily, Rego is not only alive but also still furiously creating at the top of her game. It’s high time that Tate Britain started planning an even better and larger show. In the meantime, you can fly cheaply to Madrid on easyJet and the Reina Sofia’s sumptuous catalogue is available in English.

Tom Rosenthal is the author of Paula Rego: The Complete Graphic Works.

Comments