Knowing when to accept victory is a key political skill. But it is not a universally held one among leadership cadres.

The Palestinian people, for instance, have in the past been led by men who have turned down hugely advantageous deals offering major concessions. Once rejected on grounds of not amounting to absolutely everything desired, those concessions never appear again.

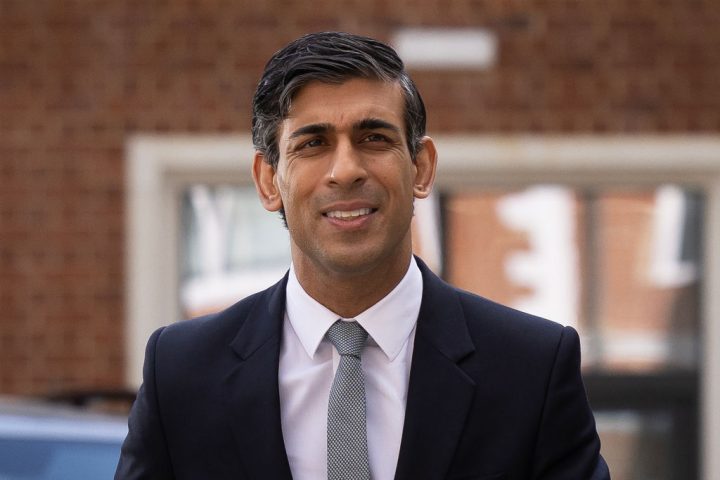

Were the Democratic Unionist Party to accept Rishi Sunak’s ‘Windsor Framework’ agreement with the EU, the party would widely be regarded to have played a blinder once the dust had settled. Having correctly called the bluff of establishment forces who foisted the original Northern Ireland Protocol upon them and led a steadfast Unionist and loyalist resistance to it, they would be seen as having achieved huge improvements and concessions.

The DUP would widely be regarded to have played a blinder once the dust had settled

If the proposed new arrangements are not quite ‘Unionist purist’ then neither is the Belfast Agreement, signed 25 years ago and institutionalising an approach according rights and respect to both political and religious traditions in Northern Ireland.

In fact, there are grounds to think the Windsor arrangement is actually more favourable to the Unionist tradition than is the Belfast Agreement. Unionists have acquired a ‘Stormont brake’ veto on new EU regulations applying to Northern Ireland which can be wielded without the need for Nationalist or non-aligned assembly members supporting it.

The new approach to goods flowing from Great Britain onto the island of Ireland also underlines the constitutional difference between the two parts of that island. Stuff heading for Northern Ireland gets to go through a green lane, while stuff intended to cross the border into the Republic will be subjected to checks.

Of course, it must rankle that there is still some involvement of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) over laws pertaining in Northern Ireland, albeit subject to the Stormont brake and consultative rights on any proposed changes. But then again, many business-minded and middle-class Unionists undoubtedly value continued membership of the European single market. Indeed many of them voted against Brexit primarily for that reason.

ECJ involvement is axiomatic with single market membership. Certainly the vast majority of northern Nationalists did not wish to leave the European Union either, considering such a divergence with the Republic’s status a boost for Unionists that would render the six counties more rather than less British. Yet Sinn Fein and other Nationalist parties have, by and large, taken Brexit in their stride and show no sign of kicking up a fuss against the Windsor Framework.

These arrangements significantly bolster Northern Ireland’s place within the UK internal market. With them in place there is every chance that the economic premium predicted by many as a result of the country having a foot in both economic camps would finally be realised. With trade flowing freely across the Irish Sea and across the Irish border, Northern Ireland would surely become a very attractive destination for inward investment.

If there were to be a referendum of the Northern Ireland public on the new arrangements – of course there won’t be – then how do DUP supporters think it would go? It seems to me that rejectionism would only flourish in the most working class and urban loyalist communities, be successfully depicted by its opponents as a road to nowhere and a counsel of despair, and be heavily defeated overall.

So my advice to Northern Ireland Unionists, as a Unionist myself, would be to take the win. Indeed, from a Brexiteer standpoint the most disturbing aspect of the Windsor Framework is surely something not related specifically to Northern Ireland at all.

During yesterday’s press conference, Ursula von der Leyen said that the UK had agreed, as part of the deal, a right for the EU to be consulted in advance whenever the UK government was proposing UK-wide regulatory changes.

Now of course the right to be consulted is not the same thing as the right to wield a veto. But it might, de facto, amount to something pretty similar at least for the foreseeable future.

Von der Leyen can look ahead at British politics and be fairly confident that the UK will be led for the entirety of her own career running the European Commission either by Keir Starmer – a man who conspired with Brussels to try and block Brexit altogether – or ‘Dear Rishi’. No wonder she was smiling. The chances of someone taking the reins anytime soon who believes in seeking a British competitive advantage over EU member states by means of radical regulatory departure appear remote.

Continued alignment, albeit not of a particularly dynamic variety, looks like the most likely prospect now. It’s turned out better than Theresa May’s lock-in but hardly amounts to the glorious new chapter for Britain that many buccaneering Brexiteers might have hoped for.

Comments