In a Victorian art dealer’s shop a woman waits with her young son while the supercilious owner examines her work; behind her two top-hatted gents interrupt their inspection of a drawing of a dancer in a tutu to give her the once-over. The woman’s shabby umbrella, propped against the counter, awaits reopening in the rain outside. She knows what the dealer will say, and so do we.

Every picture tells a story, and Emily Mary Osborn’s ‘Nameless and Friendless’ (1857) summarises the plot of Tate Britain’s latest exhibition, Now You See Us. Unlike her picture’s protagonist, Osborn was herself a successful artist in a field dominated by men – not the fate of many of the artists in the Tate’s new survey of four centuries of British art by women.

Suppress your groans; this isn’t a gender-balance tick-box exercise

Suppress your groans at the prospect of another women-only show: the curators of this encyclopaedic exhibition haven’t flung together any old female artists in a gender-balance tick-box exercise. Instead they have sought out every female artist known to have practised and exhibited in Britain between 1520 and 1920 and compiled a fascinating blow-by-blow account of their struggles to achieve parity with men.

The exceptions – Artemisia Gentileschi, Angelica Kauffman and Laura Knight – only prove the rule. To succeed, women had to play men at their own game, dispelling the perception that they could only copy – that they were good at painting flowers and portraits but couldn’t work from imagination. Kauffman challenged that myth in her allegory of a female artist practising ‘Invention’ (1778-80) – commissioned for the Council Chamber of the Royal Academy from whose deliberations, as a female member, she was excluded – but copycat works by less talented successors such as Mary Beale, whose portraits borrowed compositions from Lely and Van Dyck, tend to confirm it.

If the point is to prove that women are creative equals of men, then a smaller show focused on fewer, more original women could have landed more punches. As it is, there are too many artists here who paint like clones of more famous men. It didn’t help their cause. Ethel Sands’s reward for the flatteringly Sickertian style of her ‘Tea with Sickert’ (c.1911-12) was exclusion from the all-male Camden Town Group. The show’s stand-out works avoid stylistic tics: Lucy Kemp-Welch’s dramatic ‘Colt Hunting in the New Forest’ (1897), acquired for the Tate when she was just 28; Louise Jopling’s confident self-portrait, ‘Through the Looking Glass’ (1875), newly added to the Tate’s collection; Ethel Wright’s ‘The Music Room: Portrait of Una Dugdale’ (1912), an image as decisive as its feminist subject. Like Knight, who in 1936 became the first female artist after Kauffman to be elected a full Academician, these women didn’t faff about with masculine fashion. They had the independence to keep things simple, as did the show’s poster girl, Gwen John.

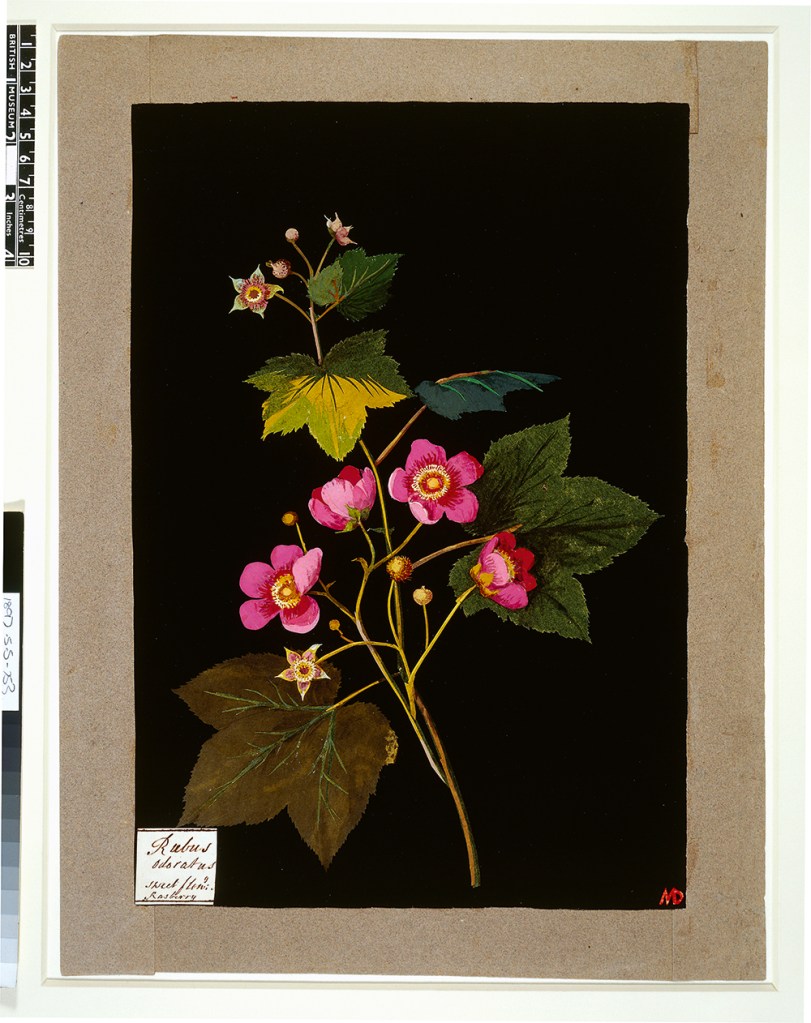

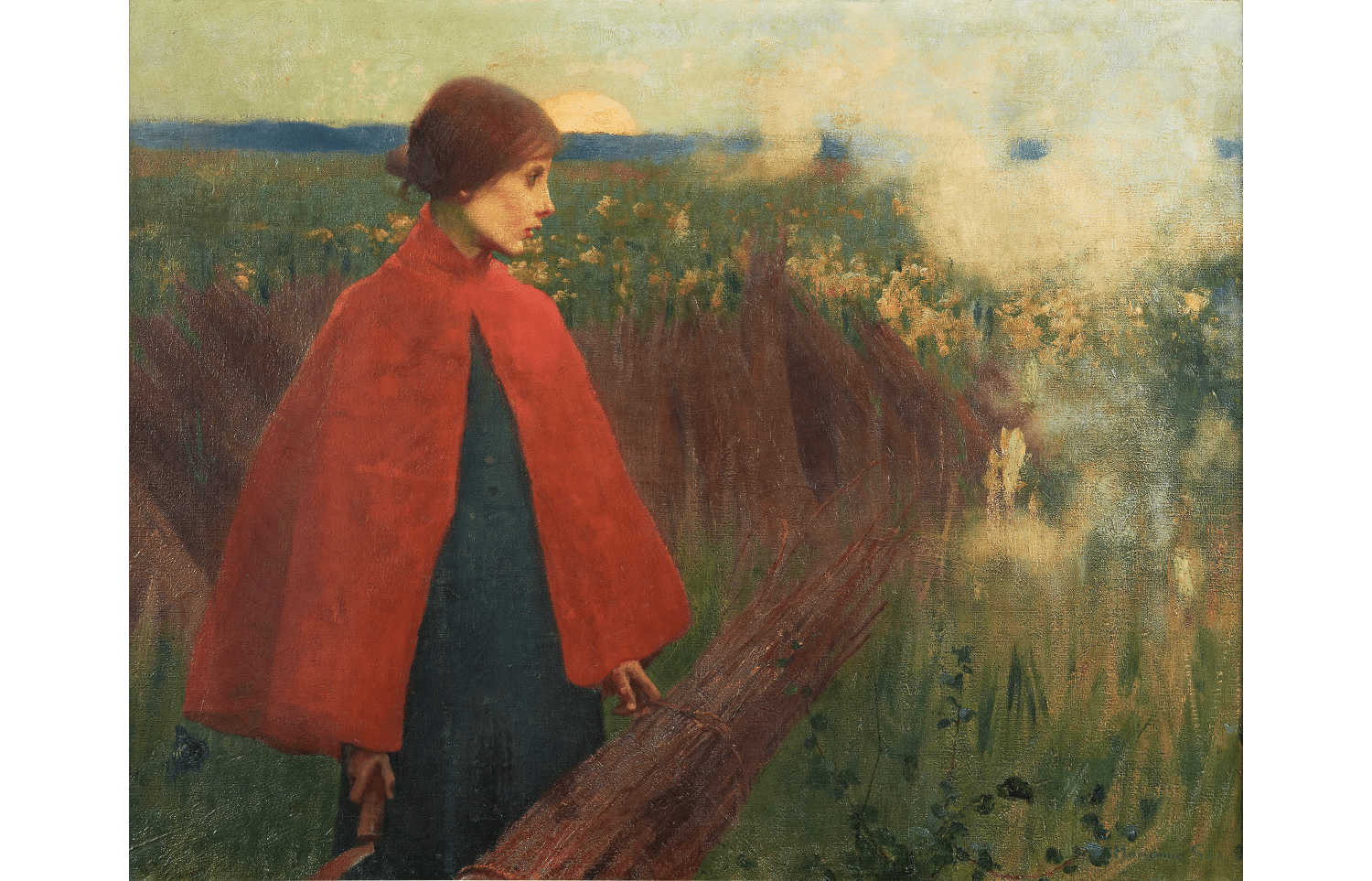

There’s another thing, non-gender-related, about the best female painters in this show: from the 18th-century Scottish portraitist Catherine Read, who studied in Paris, to the 19th-century Austrian-born Marianne Stokes, who spent time in the artists’ colony at Pont-Aven, most of them trained abroad. Stokes’s dreamlike ‘The Passing Train’ (1890), with its cloud of steam about to envelop a red-caped mystery woman in a field at sundown, is a magical invention. But imagination isn’t everything; copying has its place. The discovery of the show, for me, was the 18th-century amateur Mary Delany and the botanical collages she began making in her seventies – around the same age as Matisse began his cut-outs. Her ‘Crinum Asiaticum’ (1772-82) is as exquisite as a Karl Blossfeldt photograph and as botanically accurate: Joseph Banks swore by her reproductions. Now in the British Museum, Delany’s ‘paper mosaicks’ would have been banned from Royal Academy exhibitions as ‘baubles’, along with needlework and shell-work. (She did those, too.)

Too many artists here paint like clones of more famous men – the best avoid this

If professional status means working for money, amateur status gives an artist total freedom. An amateur woman needn’t paint like a man: she can be a complete original. Beryl Cook was a boarding house landlady when she was given the one-woman show at Plymouth Art Centre in 1975 that made her a national treasure overnight. She can hardly be described as invisible, but Cook’s jovial art, long dismissed by art world snobs as ‘popular’, is currently accruing critical bona fides in a joint exhibition at Studio Voltaire with homoerotic icon Tom of Finland. There is no doubting this woman’s powers of invention: her vision was entirely her own.

In the background of ‘Nameless and Friendless’ a clerk is making entries in a ledger, reminding us that art dealing is not just about aesthetics, it’s about what sells. Even now collectors rarely pay top dollar for art by women; Britain’s first official female war artist Anna Airy put her finger on it when she observed that galleries and buyers felt ‘safer with a man’. But if art by men still commands higher prices, art exhibitions attract more female visitors – and that’s shifting the dial.

Comments