In late middle age, William Styron was struck by a disabling illness, when everything seemed colourless, futile and empty to him. In fact, as he recalled in Darkness Visisble (1990), he was suicidally depressed. So when he died in 2006, at the age of 81, it was assumed he had taken his life. His father, a Virginia-born engineer, had, moreover, been a depressive himself, and maybe a suicidal tendency had transmitted down the generation, like a dangerous gene? In reality, the author of Sophie’s Choice had died of pneumonia, complicated by alcoholism and addiction to tranquilisers.

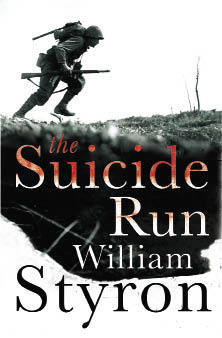

A lifelong malcontent, Styron indeed had few reasons to be cheerful. In The Suicide Run, a posthumous collection of short stories, he chronicles his gruelling experience in the US marines during the second world war. As a platoon leader stationed in Okinawa, Styron grew to detest the enemy (‘I caught the contagion of Jap hatred’), and says he would happily have killed. In pages of pungent prose, he conjures the ‘hot funky stench’ of jungle warfare in the Pacific and the terror of amphibious landings in the face of Japanese fire.

After the nightmare intensity of the marines, however, his release back into civilian life in America was even more traumatic. Like all exiles, he felt he had come home to a different world. Everywhere he went in his native Virginia, people spoke fearfully of Russia’s atom bomb and asked how long it would be before a Red Square appeared in Washington. Styron felt unable to share in the instinctive anti-Communism and, he writes in ‘Marriott, the Marine’, this only added to his feeling of loneliness and alienation. In ‘My Father’s House’, begun as a novel in 1985, he recalls his state of ‘shock’ following his Pacific ordeal and his attempts afterwards to find relief in sex and booze.

However, a burning question stalked Styron’s hoped-for recovery: why me and not the others? His survival when so many fellow marines had died had become his shame. The Suicide Run is saturated with survivor guilt and the anger felt by so many combat veterans. Few in late 1940s America were aware of the disturbance — the neurotic aftermath — that lay ahead so soon after the conflict’s end. Indeed, the effect on the psyche of those who had survived was simply not known. Having been discharged from the marines, all Styron knew for sure, he writes in ‘Blankenship’, was that his present suffering must be followed by more suffering.

Overall, The Suicide Run provides a moving account of the horrors and vainglories of war. Unfortunately, the stories are at times poorly written and brocaded with bijoux adjectives such as ‘matutinal’, ‘lowering’ and ‘sullen’. Throughout, moreover, Styron displays a lewd interest in the shape and size of women’s breasts (their ‘delicious bounce’), as well as women’s ‘adorable lips’, as often as not ‘parted in moist, concupiscent welcome’. (One woman is apostrophised, strikingly, for her ‘peekaboo panties’ and expensive perfume ‘odorous of gardenia’.) This is a shame, as Styron is a far better writer than these infelicities might suggest; I wish he had thought to iron them out.

Comments