When I know I’m going to see a film, I like to prepare. I’ll watch the trailer. Then maybe the second trailer. Sometimes a featurette.

When I know I’m going to see a film, I like to prepare. I’ll watch the trailer. Then maybe the second trailer. Sometimes a featurette. I’ll read reviews, the director’s statement of intent, interviews with the cast. It’s a terrible habit, really, arming myself with this glut of information; it is difficult to avoid spoilers in among the noise and it makes me want to talk about it, often while it’s on. ‘Oh, this is the bit where that actress messed up her lines but they left it in because it was more “real”,’ is the kind of thing I try to stop myself saying. It irritates me. I can only feel sorry for the people I’m seeing the film with.

Happily, I didn’t get chance to do any of this before I saw The Skin I Live In, and if you can make an exception for this piece (I promise I won’t spoil it), I’d recommend you do the same. The latest work from Pedro Almodóvar, the Spanish director so revered by cinema-goers that his new films are almost never called his new films but his ‘latest work’, it’s the sort of thrillingly bonkers gothic fairy tale that Black Swan could have been, had it accepted its own hysterical campness rather than taking itself so seriously.

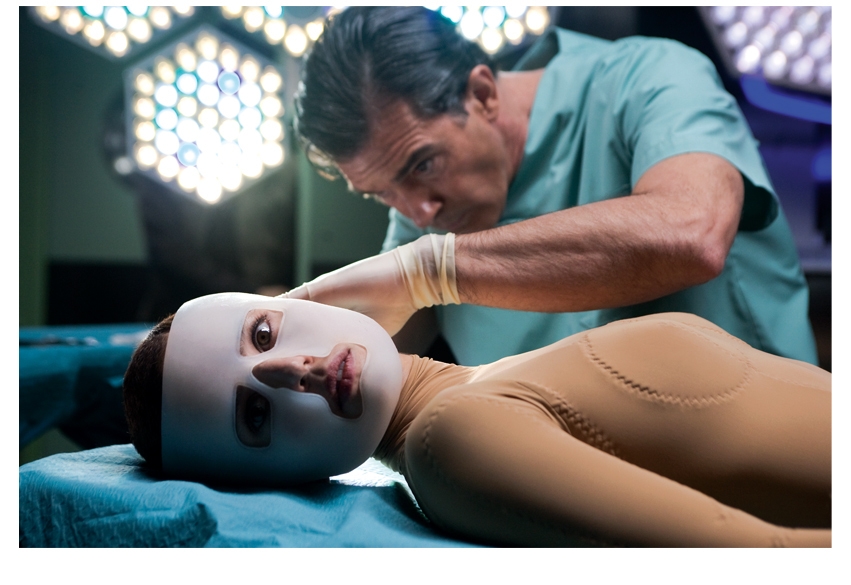

Which is not to say that The Skin I Live In is camp, though it has its moments, as the plot gets progressively more preposterous with delighted, demented precision. Where Broken Embraces, his last film (or work, if you insist), was a beautifully shot if meandering tale of love that once again used Penelope Cruz as the object of his affections, there is no such gentle touch here. Old favourite Antonio Banderas is back on board for the first time since 1990’s Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down, playing Robert Ledgard, a reclusive, brilliant doctor with, of course, a mysterious past, who has invented an artificial skin resistant to burns and injury. His colleagues are wary of the ethics of his research techniques, and this, along with the operating theatre he keeps secluded in a dark corner of his isolated mansion, suggests he is not simply driven by dedication to his craft.

Ledgard keeps the equally intriguing Vera, played with an expert balance of quiet resolve and blank resignation by Elena Anaya, locked away in a spacious room that resembles an art installation, occasionally letting himself in to smoke opium with her, though preferring to watch on a screen outside as she stretches herself, in a nude body-stocking, into graceful yoga positions. We don’t know who she is, or why he is in possession of her, but an early suicide attempt suggests this is not a happy or willing arrangement.

And then a grown man in a tiger outfit turns up uninvited to this sinister, serene house, and everything starts to unravel. An early rape scene involving this animal-costumed criminal left me uncomfortable, in that moment, because I felt it had been played for farce. This was disappointing, given that what we Almodóvar fans love most about him is his well-known love for women and the brilliant parts he creates for them. Later it becomes clear that the scene happens that way for a reason. Of course it does. I realised how pleased I was that I had turned up at the cinema with a blank slate because it meant I was completely under the film’s command. Having my reactions so thoroughly upended was an invigorating experience and I’d almost forgotten the pleasure of it.

The sheer glee of The Skin I Live In supersedes any consideration of Almodóvar’s themes, which are always tempting to indulge in, given that his films are subtitled and arty. And he certainly invites that sort of analysis here, dotting books on gender around Vera’s room, referencing Louise Bourgeois throughout, making the audience contemplate that they are watching the watcher watching. Though it’s fun to wonder what he’s trying to get at, what wider points he’s trying to make — and they are not entirely clear — there’s no need to be deathly earnest about it. It’s the playfulness that really pulls this together, the thrilling sense of having no idea what will happen next, because nothing, truly nothing, is off-limits. But I shouldn’t have told you that, because now you’ll be expecting it, and the key to enjoying this is not to expect a thing. Then again, this could be a double-bluff. You won’t know, and as a convert to not knowing, I can recommend it.

Comments