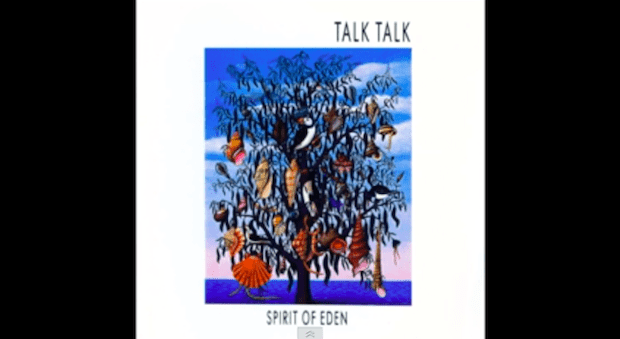

First impressions always count, and they are almost always wrong. This is particularly pertinent if you review albums for a living, as I used to years ago. You would listen once, maybe twice, possibly three times if you were really being good, and then form an opinion, which was as much based on your preconceptions — and indeed taste — as on anything you had heard in the grooves. And then you would write your review. You would then forget about the record in question because there were so many others to listen to. It was essentially an industrial process, and it quickly ground my enthusiasm for music into dust. Music, though, is one of the few art forms, if not the only one, in which appreciation is inexorably tied to repetition. We only need to read a book or see a film once to have an opinion about it and, in most cases, to have exhausted all it has to offer. But a good record is something we have to live with, and we may not even realise it’s any good until we have lived with it for a while. It works the other way, too. If you are a fan of a particular band or artist, you will have listened to their worst album over and over and over again, desperately waiting to hear something that simply isn’t there. And when you finally admit to yourself that it is a vast steaming mound of the purest excrement, it feels like an epiphany of sorts, a liberation even. Our relationships with particular records can be long and complicated, even tortured. Around a quarter of a century ago, then, I heard and immediately loved The Colour of Spring, the third album by Talk Talk, a sort of post-new-romantic pop band from the wilds of Essex who were then developing in more arcane, acoustic directions. ‘Life’s What You Make It’ (reasonable advice) was the relatively upbeat hit, but the general mood was dark and slow and pessimistic, while songwriter Mark Hollis was becoming more interested in the space between the notes than in the notes themselves. This development was more marked still on their next album Spirit of Eden (1988), which I found incomprehensible. Its six longish songs had slow build-ups, long shuffles of nothing very much going on and occasional bursts of discordance to keep you awake, while Hollis’s melancholic lyrics now seemed to veer close to mental illness. I listened to it from time to time over the years, but still couldn’t work it out. Was it a work of genius, or self-indulgent tripe? Whatever it was, it always felt like hard work, and I always returned with relief to the relative straightforwardness of The Colour of Spring. Not everything is for everyone, I figured. Just because every time you hear James Blunt sing you want to rip your ears off and stuff them in his mouth doesn’t mean that someone somewhere might not love everything he does. As the years rolled by, though, Spirit of Eden acquired a reputation, first as a lost classic, and then as a true, widely acknowledged, diamond-encrusted classic. Other bands cited it as inspiration. It was a record played on more than averagely miserable tour buses. So the other day I put it on again, for probably the first time in seven years, and maybe for the 20th time overall. And PING! I got it, completely and instantly. The tunes are there. The dynamics are fascinating. The quietness is illusory. How could I have missed all this? How can I have been so deaf? And now I hear it, I can also hear how this band and this album have seeped into so much we listen to today. Here’s Guy Garvey of Elbow, talking to Mojo last year: ‘Mark Hollis started from punk and by his own admission he had no musical ability. To go from only having the urge, to writing some of the most timeless, intricate and original music ever is as impressive as the moon landings for me.’ Timeless is the crucial word here: by steering away from the synthetics and drum sounds of the 1980s, Hollis made music that sounded out of its time then, and out of all time now. It is, above all, deeply introverted music. Hollis and his bandmates couldn’t possibly play it live, wouldn’t make a video, probably didn’t go on Multi-Coloured Swapshop to promote it. Later on, he made two even more self-absorbed and difficult albums and then retired from the music business. Maybe it was other people’s first impressions that finally got to him, the ones that counted, even if they were almost always wrong.

Marcus Berkmann

Talk Talk bears repetition

Which album would you gladly hear again and again? Marcus Berkmann picks Spirit of Eden

issue 12 October 2013

Comments