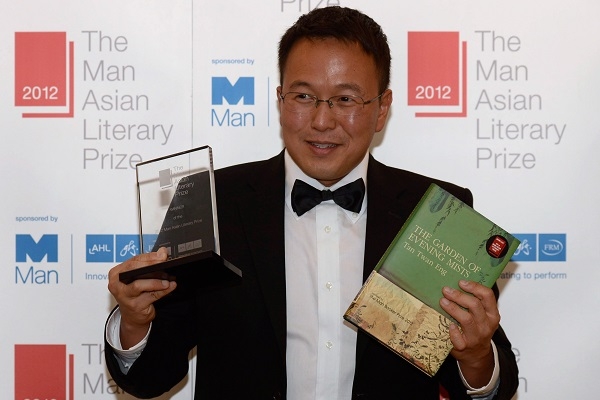

Tan Twan Eng’s first novel was long-listed for the Man Booker Prize, his second was shortlisted and then won the Man Asian Literary Prize. To say that his work over the past five years has received praise and attention would be something of an understatement. Likened to Ishiguro and Ondaatje, his work explores the point at which untold personal history collides with the bellicose history of mid-twentieth century East Asia.

In The Gift of Rain the elderly Philip Hutton is living out his days as a postcolonial remnant in his childhood home of Penang, with little but his memories to keep him company. These are revisited with arrival of Michiko, the former lover of Japanese diplomat Hayato Endo, with whom Philip had developed a strong relationship in the 1930s. Their relationship is jeopardised when loyalties of family, nation and martial arts clash as the Japanese come to occupy Malaya in 1941.

His second novel, The Garden of Evening Mists similarly looks at the Japanese occupation of Malaysia. Judge Teoh Yun Ling, who survived internment in a brutal Japanese camp, has spent years working to prosecute Japanese war criminals. Now she is faced with aphasia, she decides to address her difficult memories, as the guerrilla war of The Malayan Emergency rages in the distant hills and jungles. Through her conversations with Professor Tatsuji, she recounts her relationship with former Japanese imperial gardener Aritomo, whose guidance she sought in creating a memorial garden for her sister who died in the camp. Yet in looking back with Tatsuji, Aritomo’s role in the war and her life become as morally strenuous as the divided loyalties which Hutton and Endo suffer in the first novel.

You are soon closing the Asia House Festival of Asian Literature and you have won the Man Asian Literary Prize. How useful do you find the term ‘Asian’ with regards to categorising your writing?

Literature should open minds, widen a reader’s awareness of the world. Any form of labelling is limiting and places writers and their works into self-contained worlds. Such categorization is also subjective and confusing. My first two novels are set in Malaya, but if I were to set my next novel in London or Amsterdam or South Africa, would it be categorized as ‘Asian’ writing? If Hilary Mantel were to write a trilogy about India or China or Japan, how would one go about categorizing her books?

Nearly all previous winners of the prize have been translations into English. Why do you choose to write in English?

My parents studied in English-medium schools, so from an early age I was familiar and comfortable with English. I’m multilingual, but my reading is confined completely to English. I think and dream in English, and I have no alternative but to write in English.

You once said that Philip Hutton in The Gift of Rain, who is of Sino-British heritage, ‘wants – like all of us – a place to belong to.’ You are from Penang, studied in London, worked in Kuala Lumpur and live in Cape Town. Where would you say you felt you belong to?

I divide my time between Kuala Lumpur and Cape Town, and when I’m in one place I miss the other. It’s a common condition for today’s people – we move from city to city, country to country. The one place I can say I truly belong, where I feel anchored, is at my desk when I’m deep in my writing.

How does the idea of belonging fit into a multicultural nation like Malaysia?

The overlapping of cultures and communities makes it easy for anyone to fit in. We’re very welcoming to outsiders, but your sense of belonging to a place will depend on how open you are to different ways of doing things.

And how has your work been received in Malaysia?

The majority of Malaysians are not great readers of fiction. The Man Booker Prize shortlisting and winning the Man Asian Literary Prize has made more Malaysians aware of my novels. They’re more eager to read them, and they’re very supportive of my work now.

Both your novels revolve around the period of the Japanese occupation of Malaysia. What particularly draws you to this time?

Up to that point in time, the Japanese Occupation was the most catastrophic thing to have happened in Malaysian history. It’s a thick demarcation, severing the past from the future; it marked the end of the British colonial empire and the beginning of self-rule. It showed the people that the Western powers were not invincible. After the war, the colonies demanded, and in some cases, fought for independence. It was a period of great change and upheaval, but I was more interested in exploring how ordinary men and women go through their day-to-day lives, how they cope with remembering and forgetting.

Do you think that there is an ongoing effect of the occupation in Malaysia?

Some of the older generation feels rancorous, and I can’t speak for those who experienced the Occupation, but for those of us born after the war, it’s not something we think much about. For many of the younger people, the Japanese Occupation is a fading myth, not relevant to them. In the early 1980s the Malaysian government implemented a ‘Look East’ policy – we were encouraged to emulate the Japanese in their work habits, their industriousness and discipline. Students were sent to Japan to study. We bought cars and electronic products made in Japan. And in the last few years Malaysia – in particular the island of Penang – has become a popular second home for a large number of Japanese retirees.

Often your characters are placed in situations which require a certain amount of moral ambiguity or complexity and the difference between right and wrong becomes blurred. Does your training as a lawyer influence your writing in this sense?

It trained me to evaluate every word I use, to appreciate the nuances of language. A lawyer has to see all sides of the issues, and so must a writer. My characters are morally ambiguous and complex because life isn’t clear-cut black and white. It’s more interesting – and challenging – to write about such characters.

In both the works there is a central relationship of apprenticeship or of a student and a mentor, the first involving the martial art of aikido and the second gardening. What attracts you to exploring such a relationship?

At the start of his training, the apprentice is completely obedient to the mentor; but as he learns more and time passes, the relationship between the two changes. The apprentice grows stronger, more skilful, perhaps even surpassing his mentor eventually. I wanted to explore the shifting balance of power between a mentor and the apprentice, and what would happen if such a relationship went beyond the boundaries of the lessons and affected their lives

Having practiced aikido obsessively for ten years, I saw how some students could be completely in awe of their mentors, following them blindly. I find such total obedience to authority difficult to understand. I had a lot of respect for my teachers, but I was always questioning what they taught.

Your first novel is narrated from a male viewpoint and your second from a female. Is there a reason behind moving from one gender to another?

Female Japanese POWs have not been extensively explored in fiction, and I wanted to write about them, to see things from their point of view. It was difficult to write the character of Yun Ling in The Garden of Evening Mists, not because she was a woman, but because of what she had experienced in the war. When I began writing the novel Yun Ling was difficult for me to understand – she held her emotions and her memories tightly to herself and refused to let me in. It wasn’t until almost at the end of the book, when I set down what happened to her, that she opened up her thoughts and emotions to me. I had to return to the first page and rewrite the book.

How did you find the transition more generally from writing your first novel to your second?

Other writers had warned me that the second book is the hardest to write, and it was true. I was more confident, but there was also more pressure – largely self-imposed – on me. Each book I write has to be better written than the previous one. One has to grow, to evolve. Each book is different – it has different situations, different requirements and different ways of looking at the world. I’m starting to realise that it doesn’t get easier to write.

Finally, it could be said that your writing is similar to Kazuo Ishiguro’s in its preoccupation with twentieth century history and memory. Would you consider him as one of your influences?

I admire a lot of writers: Julian Barnes, David Mitchell, Martin Booth, Salman Rushdie, Colm Toibin, Vladimir Nabokov, Hilary Mantel … Kazuo Ishiguro is one of my influences, but I’m always learning something from every writer I read as well.

The Garden of Evening Mists by Tan Twan Eng is published in paperback on 2nd May (Canongate Books, £8.99). He will be appearing at Asia House Festival of Asian Literature on 22nd May at 18.45pm.

Comments