Never judge a country by its airport road. Georgia’s, from international arrivals to the heart of Tbilisi, is impeccable. The George W. Bush highway (yes, really) is smooth asphalt, with chic electric cars humming down avenues, punctuated by spanking new Lukoil petrol stations with fuel at dirt-cheap prices. It is impeccably clean. And when you reach the parliament building downtown, they have almost finished clearing up the detritus from three consecutive nights of protests, rubber bullets, tear gas and riot police.

Tbilisi’s highway was built during the country’s most recent economic sugar rush, when a good-looking young president, Mikheil Saakashvili, was in his brief but glamorous heyday. As a Kennedy-esque reformer, he sacked the police force, scourged corruption and cleaned up the country. But he later fell back into heavy-handed authoritarianism. Last weekend, the sunlit way-stations of progress – EU and even Nato membership – receded with the crowds. Saakashvili is in a jail hospital, his once-generous 120kg almost halved by illness amid rumours of dementia and even, improbably, poisoning.

As ever, it is feast and, more often, famine in Georgia, a country of 3.7 million that has had more invaders than Sicily. Romans, Persians, Syrians, Genghis Khan, and, of course, the Russians have all had their turn raping and pillaging in the temperate vineyards, orchards and vegetable fields that spill out below the great Caucasian massif that should be a defensive wall, but isn’t. Today, as the once good-time-boy president wastes away, thousands of Russian conscript-dodgers and digital nomads mingle with Ukrainian war refugees and pour over the borders to push up the prices of everything. And meanwhile the country totters on a tightrope between appeasing the widely disliked Bear or, some fear, facing its own existential apocalypse.

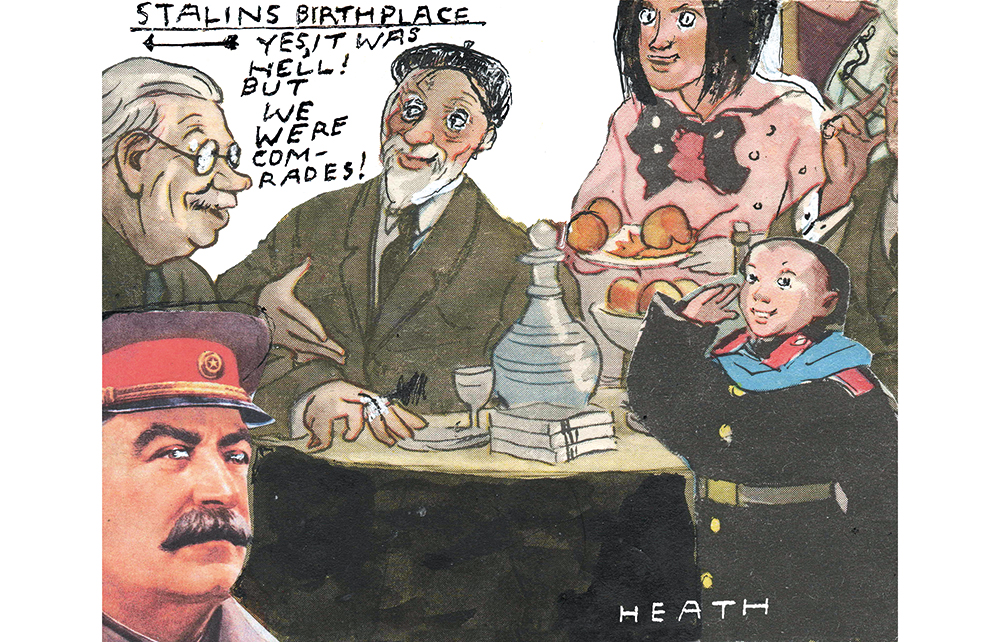

It’s not that Georgia hasn’t seen it all before – in fact, you could argue that it was Moscow’s trial run. As long ago as 1992, soon after the Soviet Union fell, in Abkhazia in the north-west and South Ossetia in the centre of the country there were clashes with little green men. Then again in 2008, after what many argued were Russian provocations, hundreds died and thousands more were displaced in a full-scale war. Today, the two regions are Georgia’s Donbas and Luhansk – closed-frontiered client states of Moscow: 20 per cent of the country, annexed. So what to do? Ask Tamar, a 75-year-old guide in Joseph Stalin’s sepulchral museum in his Georgian birthplace of Gori, or Tariel, a 62-year-old former Red Army veteran, and the answer is: ‘Don’t provoke.’ Both spent more than half their lives as Soviet citizens; both would like to join the EU but feel that Nato membership is a step too far. ‘When the Russians come, they never leave,’ Tariel warns.

But it’s all about age. Saba Buadze, 31, a svelte, western-educated Tbilisi city councillor, claims polls show 85 per cent of Georgians favour full integration into the western family of nations. Yet, he argues, the ruling Georgian Dream party is deliberately engineering roadblocks. The now withdrawn foreign influence legislation – modelled on Moscow’s – would have served the dual purpose of handing draconian powers to control outside companies and media to the state, but also proved a major stumbling block to EU candidate status – already granted to Ukraine and Moldova but denied to Georgia. Sitting in a Tbilisi hipster hotel, Buadze describes himself as ‘centre-right’ and acknowledges that he is part of Georgia’s upper crust. But when he goes on he reveals a revolutionary of sorts. ‘The ruling elite know exactly what they are doing,’ he says. ‘They are trying to manoeuvre their electorate with fear of war with Russia and by saying that these people [the West] are trying to undermine our values and national identity.’ Last week’s protests, though, showed that most are not buying it. ‘I am very hopeful that these past days have shown that we will not fall back into the Russians’ hands,’ he says.

Tbilisi today feels a bit like the 1930s Bucharest of Olivia Manning’s Balkan Trilogy – a tinderbox where something possibly unpleasant is about to happen. The conspiracy theorists – not always wrong – believe that Georgia’s sole billionaire, Bidzina Ivanishvili, a computer salesman turned metals, mining and real-estate mogul, is the puppet-master. In 2012, he founded the Georgian Dream party that now holds power, defeated Saakashvili, briefly served as prime minister, and retreated into hermit-like silence, announcing that he was withdrawing from public life. But his placemen are still there.

Buadze, who served briefly as legal aide to the current Prime Minister, Irakli Garibashvili, believes Ivanishvili is also walking a tightrope. Back Russia and he may lose his western assets; back the West and he may lose something much harder to recover. Two years ago, the reclusive billionaire all but disappeared. Yet there above the capital, high over the higgledy-piggledy Old Town and the classical grandeur of the boulevards, glowers a mountain eyrie – a vast, illuminated airport terminal of a palace. This is the townhouse of Ivanishvili, to his enemies a Svengali Dr No who allegedly owns everything and everyone, and talks to no one – except, perhaps, the Kremlin.

Comments