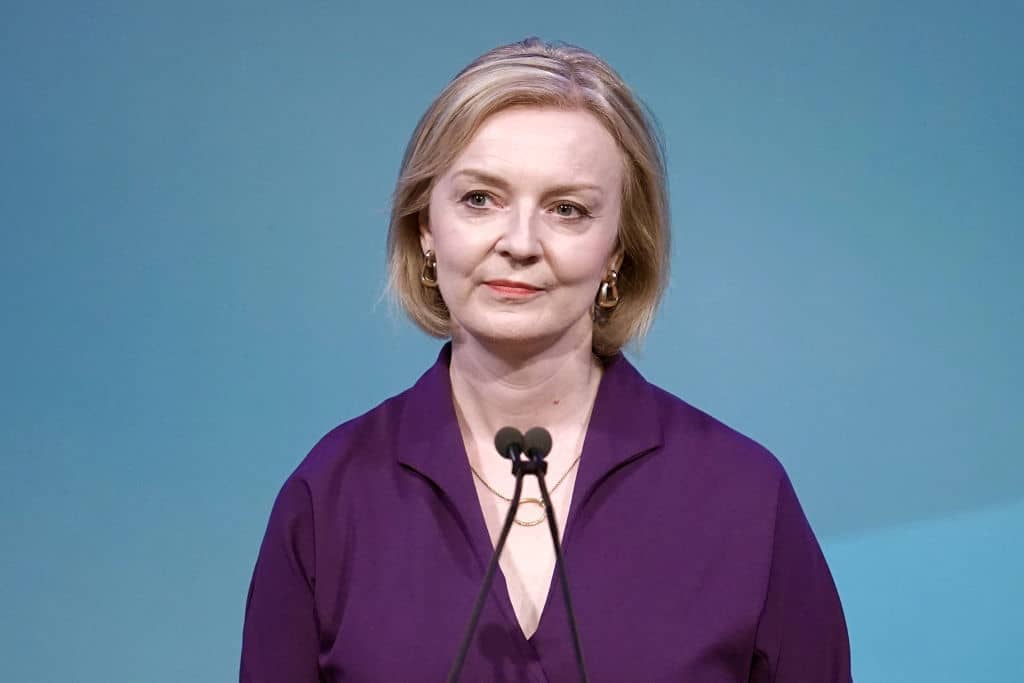

The new Prime Minister’s honeymoon starts and ends today. Once Liz Truss formally enters Downing Street tomorrow she will be under pressure to tackle the enormous economic crises facing the country, with very little time to announce her policy plans. Truss herself has pledged to reveal her plan for rising energy bills within the first week of her premiership, and her plans to slash tax within the first month. While at the forefront of political discussion, these are but a few of the emergencies that the government must grapple with in the weeks and months ahead. Below are ten graphs that the Truss administration can’t ignore if she and her government are to get the country back on track.

The most immediate pressure on Truss is to announce her plans for dealing with skyrocketing energy bills, now that Ofgem has announced that the next price cap lifts to £3,549 per year, a rise of 80 per cent. Having originally downplayed plans for more direct cash top-ups, it’s been acknowledged by the Truss campaign in recent weeks that the £15 billion subsidy package announced by Rishi Sunak in May would need to be extended – and substantially so.

But there are whispers now that Truss might consider another U-turn on energy bills: having ruled out an official price cap freeze (which Labour is calling for) there is now indication that this will at least be discussed as a policy option. The decision to ‘freeze’ energy bills is, in reality, no such thing: domestic politicians can’t control the global price of energy. It is, instead, a transfer of rising energy costs from the consumer to future taxpayers, as the government would likely borrowing the many billions needed to cover the costs (it’s estimated a year of ‘freezing’ the cap for a year at the April 2022 level of £1,971 would cost roughly £60 billion – about the same as the entire furlough scheme).

This might cure political headaches in the very short-term, as it would be a way of keeping customer bills lower this winter. But it heavily jeopardises another promise that Truss has made: that there will be no mandatory energy rationing this winter. Already the UK is at the mercy of countries like France and Belgium for energy imports this winter. And as France is discovering now, having so-called ‘capped’ energy bills, this policy does nothing to incentivise people from cutting back on energy usage where they safely can, and supplies are running low. Just last week France’s Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne warned that if consumption went on in France as in non-crisis times, rationing would become inevitable. If the UK implements similar policies, state-mandated rationing will only become more likely.

The new Prime Minister’s honeymoon starts and ends today

But it isn’t just energy prices that are causing household bills to soar. Looking at the breakdown of where price hikes are most acute, energy is only part of the problem. Household energy costs and petrol, while contributing heavily to growing financial burdens for families, make up less than half of the percentage point increase to CPIH inflation right now, as things like the price of food and domestic services are also skyrocketing. This is a snag in Liz Truss’s agenda to use tax cuts to help with the cost-of-living crisis. While allowing people to keep more of their own cash will undoubtedly help over the next few months and years, plans to temporarily slash VAT by five percentage points will do little to help with the cost of food, which is already VAT-exempt, and rising.

All this puts into focus just how paramount it is for Truss’s government to tackle the headline inflation rate, which is now in double digits and expected to rise further before it peaks. Forecasts are increasingly worrying, with estimates now that inflation could rise to close to 20 per cent on the year.

Truss’s main plan to tackle inflation is to create space for the Bank of England to hike interest rates faster and in bigger intervals, by loosening fiscal policy – which, in turn, should allow for tighter monetary policy. But this plan will still require central bankers to shake up their slow and steady attitudes and play ball with the Treasury – a decision that ultimately rests with the Bank, as Truss has categorically ruled out making changes to its independence.

What Truss is insistent she can control, however, is the extent to which the UK economy grows in future, centring her campaign largely around growth-boosting tax cuts and (vague) plans for supply-side reforms to get the economy moving again. But the new PM has her work cut out for her. Forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility suggest that the UK economy will remain essentially stagnant in the next few years, while the prospect of recession still hangs over Britain, with the economy having contracted by 0.1 per cent in Q2, and could well show another contraction in Q3.

Yet for all the focus on official economic data, the biggest determining factor in making or breaking the Truss premiership could well be what happens to the NHS waiting list, as the Tories currently face going into the next election with one in six residents in England waiting for care.

Truss pledged this weekend that the waiting list would fall under her premiership – but according to internal data leaked to The Spectator back in February, the waiting list is expected to rise by almost another three million before it peaks, and that’s the central scenario (in the downside scenario, it rises to over ten million). How Truss plans to get this wait list down rapidly without any serious overhaul of the current system – something both she and Sunak ruled out on the campaign trail – remains a mystery.

Meanwhile, patients suffer, and the consequences of having even more limited access to healthcare are making themselves known. The number of excess deaths has hovered around 1,000 for 15 weeks of this year, but as Michael Simmons notes, ‘unlike Covid deaths,’ these deaths, ‘are met with near silence.’ He reveals that deaths are notably high for 30 to 59-year-olds, who are clearly struggling to get access to immediate treatment when something goes wrong. This scandal of young and – in many cases – unnecessary deaths is only going to grow in the winter months when the health service is under even more strain.

All these emergencies will take precedence over medium-term economic problems, but those will still need the attention of the Truss government, especially as she considers the party’s next pitch to the electorate in a year or two’s time.

The economy is also not going to grow as Truss imagines without addressing the five million working-age people who have fallen off the grid. Especially with such a tight labour market (still hovering near the record of 1.3 million job vacancies), it is difficult to see how these gaps are closed (and indeed how inflation is brought down in domestic services) without increasing their participation in the workforce.

And then there is the policy area near and dear to the new Prime Minister’s heart. Long before the pandemic hit, prices soared and the NHS waiting list hit record highs, it was universally acknowledged that the housing sector was broken, stopping young adults from even dreaming of the day they could own a home. While Truss scaled back her ambitions for planning overhaul and vast housebuilding during the campaign, she still hinted heavily that this was a priority for her. But doing something about it will take much more than policy overhaul – it will take arm-twisting within her own party and a big dose of political capital to convince Tory protectionists (of which there are many) that creating a new generation of homeowners isn’t just ethically correct, but politically necessary for the party’s long-term survival.

This will be the underlying challenge at the heart of every policy decision Truss makes as prime minister: figuring out how to bring her party along with her. Having won the leadership contest by a closer margin than the polls suggested (57.4 per cent to 42.6 per cent), she will have to convince many of her colleagues, as well as the nation, that her plans for getting the country out of its economic slump are the right ones. And there is no shortage of problems to address.

You can follow the Truss premiership at The Spectator's data hub, updated daily.

Comments