It may come as a surprise to some that, in itself, being homosexual has never been illegal in Britain. But, for hundreds of years, homosexual acts between consenting males were regarded as criminal offences. Thousands of men of all ages were prosecuted, sent to prison – or worse. One of these was Alan Turing, whose brilliant work on artificial intelligence was pivotal to the success of the Bletchley Park code breakers in World War Two. In 1952, Turing was convicted of gross indecency and, in order to escape imprisonment, agreed to undergo chemical castration. But while Turing’s ordeal is difficult to imagine now, does pardoning him – and others convicted under such laws – do any good?

When Turing received his Royal Pardon, there was much celebration. Finally a man who had done such vital work for his country had been vindicated. Yet was this rare use of the Royal Prerogative merely an inane gesture? After all, a Royal Pardon wasn’t much use for Turing, who died in 1954. And why should Turing be pardoned but not, say, Oscar Wilde? My own objection was more fundamental. The Turing pardon was an attempt to rewrite history. Whatever we now think of the law as it stood in 1952, it was the law. And Turing had broken it. That in no way detracts from the brilliance of the man and the impact and value of his work. It is merely a statement of historical fact.

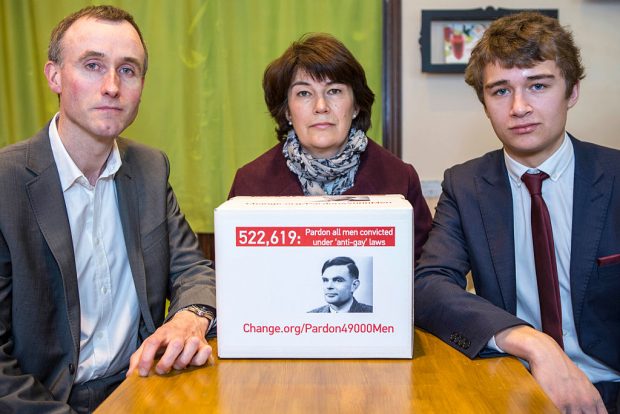

What I feared would happen has now come to pass. Last week, Theresa May’s Government announced its intention to posthumously pardon thousands of gay and bisexual men convicted of offences that have since been decriminalised. Apparently, such convictions will now be quashed automatically. And for those offenders who are still alive, there will also be a statutory procedure whereby convictions can be ‘disregarded’. Justice Minister Sam Gyimah hailed the policy, saying that:

‘It is hugely important that we pardon people convicted of historical sexual offences who would be innocent of any crime today.’

But is it? And if it is, why stop with sexual offences? In ages past there were many acts that were deemed criminal offences, but aren’t any more. Why not issue pardons for all the suffragettes (including my great aunt) who were fined or imprisoned? What about all those unfortunates who were transported to Australia for offences as trivial as stealing a hunk of bread? What about the Puritan lawyer William Prynne, who had his cheeks branded, his ears cut off and his nose slit for having written a pamphlet that displeased Charles I?

A decade ago, Parliament approved legislation that granted posthumous pardons to all British soldiers executed for cowardice during the First World War. Some of these men were undoubtedly suffering from psychiatric conditions. But others were not. The blanket pardons that Parliament authorised applied equally to deliberate deserters – genuine cowards among them.

We cannot rewrite the past and it smacks of Stalinism if we invoke the law in an attempt to do so, no matter how upset we may be with the deeds of our forebears. Nor have we any right to judge the past by the standards of the present. In any case, a pardon – be it royal or statutory – is not an exoneration. Whether we like it or not, the men who were shot for desertion in the Great War remain guilty as charged. So does Alan Turing. And so will all those homosexual men who fell foul of laws that have now been repealed.

Comments