Michael Gove has narrated this article for you to listen to.

It will probably only damn me further in the eyes of many, but when I was a government minister I often used to ask Labour predecessors for advice. Tony Blair especially. He may have felt it was a forlorn exercise ever offering me his wisdom, especially when I went on to back Brexit, support parliament’s prorogation under Boris and defend Dominic Cummings against all comers, but I always appreciated his insights, even when we disagreed. No position is so strong, no policy so perfect, that it cannot benefit from being tested by critics. If those critics have experience of office, know its powers and limitations, so much the better. And few know office better than Blair.

The anger the country feels about the rape gang scandal is real and won’t be assuaged unless action is taken

Once, when we were discussing the destabilising effect of roiling, raucous social media assaults on a government struggling in the polls, Blair offered a simple prescription, in his trademark aphoristic style. ‘The politics of anger,’ he stated, ‘needs to be met with the politics of answers.’ In other words – don’t ignore what unhappy voters are telling you, don’t get distracted by who you think might be exploiting their discontent, don’t try to police tone, shoot messengers or hope popular disquiet will simply fade as the news cycle moves on. Make sure that you address the real causes of anger properly and promptly, or you will forfeit the right to govern.

It’s advice this government should take now. The anger the country feels about the rape gang scandal is real and deep and won’t be assuaged unless action is taken and answers are forthcoming. That means establishing a new national inquiry and ensuring its work results in demonstrable change in a swath of policy areas before the next general election.

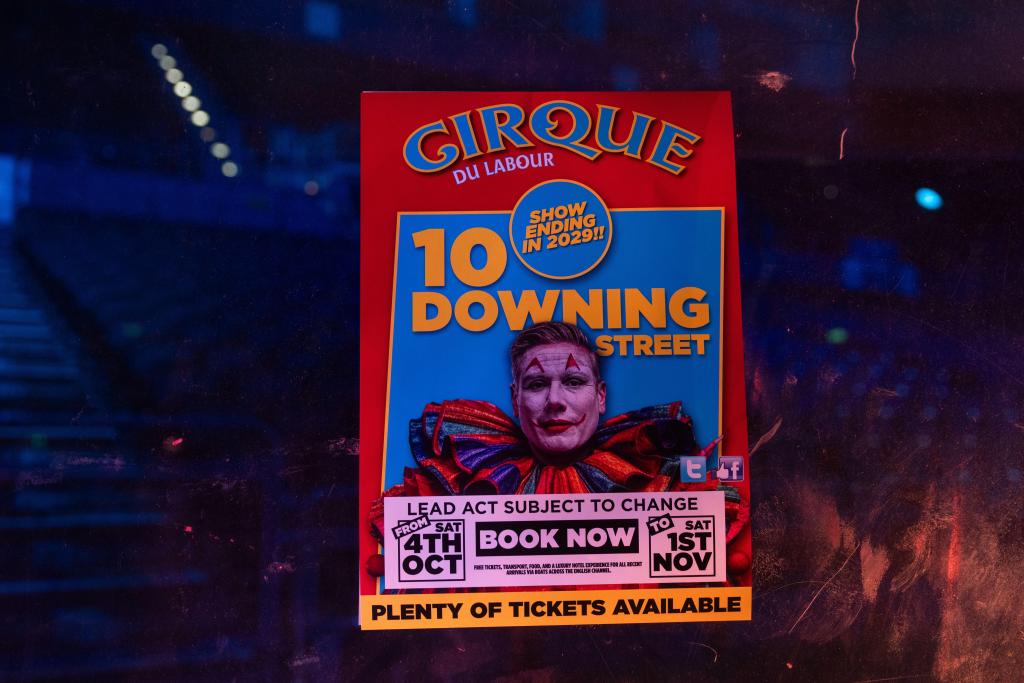

I can understand why Keir Starmer doesn’t want to go there. He will feel that, as the then director of public prosecutions, he did good work in improving how these cases were prosecuted. He is clearly uncomfortable with the way in which pressure to act has been amplified by Elon Musk’s campaign on X, and he also seems to believe that some of those most ardent in making the case for an inquiry have a ‘far-right’ agenda which it’s his Fabian duty to resist. But honestly, he must get over himself. He’s no longer the head of the CPS defending its practices, and he’s not a centrist dad podcaster paid to deprecate populism. He’s the Prime Minister, who has a direct responsibility for resolving questions that threaten faith in our institutions – from the police to social work to local government – and call into question the success of our model of migrant integration.

The reasons he has publicly given for resisting an inquiry are flimsier than a paper aeroplane in a hurricane. He argues that we’ve already had an investigation – Alexis Jay’s Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse. But that inquiry scarcely touched on the rape gangs. Instead, it was disproportionately occupied with pursuing bogus and mischievous allegations about ‘establishment’ figures supposedly involved in child abuse rings, from the former cabinet minister Leon Brittan to the retired Field Marshal

Edwin Bramall.

Starmer argues that because the Jay inquiry took seven years, another would be similarly time-consuming. But that’s only true if it’s similarly unfocused. The right terms of reference and the right team could report much more rapidly. In 2012 when I ordered an inquiry into the safety of children’s homes in the wake of the Rochdale scandal, it reported within two months.

Starmer also maintains that it’s better to devote energy to implementing the Jay recommendations than to set out to look at the scandal anew. But while some of the Jay recommendations have merit, others are either spurious exercises in empty symbolism (such as the tokenistic call for a cabinet-level minister for children) or are potentially counterproductive (such as the legislation on mandatory reporting of child abuse allegations, which is an invitation to swamp the police with poorly evidenced complaints). None of the recommendations begins to address the difficult questions raised by the rape gang scandal.

There are questions about our policing. To what extent has the Macpherson report’s finding of ‘institutional racism’ in the Met decades ago had a detrimental effect on investigations? It’s not just with respect to rape gangs that authorities failed to investigate crimes for fear of being called racist – the Manchester Arena bomber was not stopped because of similar fears. Have the police who were responsible for past failures been properly held to account? Even when there has been action, as in Rotherham with Operation Linden, senior officers were not the principal focus of inquiry. And what evidence is there that police practice has changed? Given that the West Mercia superintendent who played down child abuse in Telford is now Director of Operational Standards at the College of Policing, it seems reasonable to ask whether police standards are operating in quite the right way.

An inquiry could also ask if our social workers are being trained and managed properly, if the taxi firms and private rental homes that were the scenes of horrific abuse have been investigated thoroughly, and if the court transcripts from the 50 or so communities where this abuse occurred have been analysed so comprehensive lessons can be learned. It could ask why these crimes appear to have been disproportionately perpetrated by men not just from the Pakistani heritage community but from Kashmir. What cultural factors, from cousin marriage to political clannishness, went alongside these crimes? How can they be identified and remedied?

Starmer could have all these questions rigorously, sensitively and speedily investigated by a tough-minded former minister from the no-nonsense Labour right – a John Hutton or John Spellar – and demonstrate that his party can provide answers. Otherwise, the anger will not disappear. But his majority will.

With the news that Labour will allow limited inquiries into the grooming gangs, Oscar Edmondson speaks to Katy Balls and Isabel Hardman on the latest Coffee House Shots podcast:

Comments