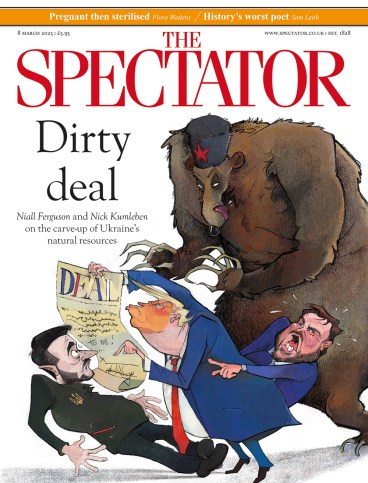

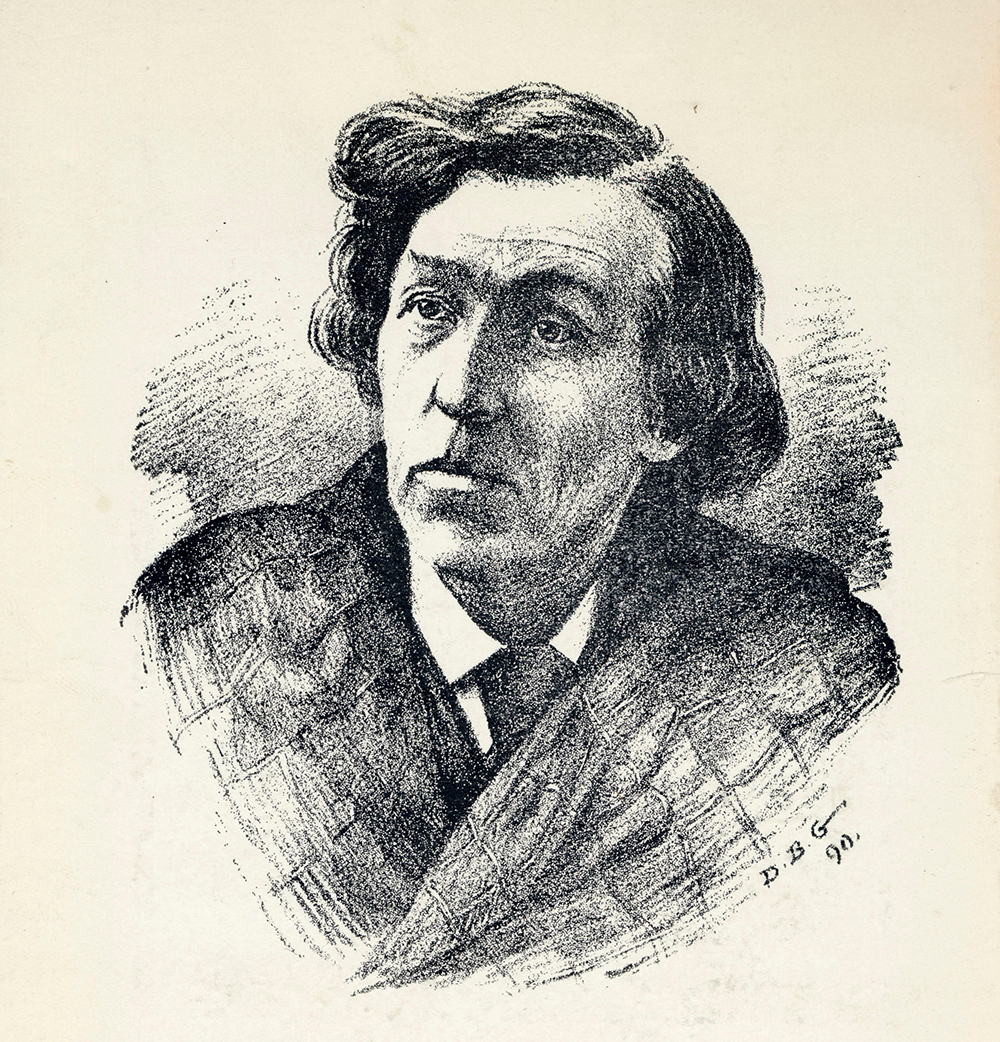

‘Not marble nor the gilded monuments of princes,’ wrote Shakespeare, ‘shall outlive this powerful rhyme.’ To be a great poet, as the Stratford man knew, is to be immortal. But there’s another way to achieve immortality through verse – and that is the route taken by William McGonagall, the ‘worst poet in history’, who was born 200 years ago this month. His star, I’m pleased to say, shows no sign of fading.

He has, as is only proper, an adjective. You can be Keatsian, Eliotian, Homeric. Or, like most of us when we sit down to write a poem, you can be McGonagallesque. His name is so much a byword for doggerel that a version of him – William Rees-McGonagall – is a Private Eye running joke to this day.

It’s not nothing to be the worst poet in history. God knows, the world has never been undersupplied with bad poets. ‘Tear him for his bad verses!’ yelps the mob in Julius Caesar, cheerfully, on discovering they’ve laid hold of Cinna the poet rather than Cinna the conspirator. To be bad at poetry is to compete in a crowded field. So why of all the millions of bad poets does McGonagall come out on top? Why is it that McGonagall survives and, say, Joseph Gwyer (the potato poet of Penge) languishes in relative obscurity? What is it that makes McGonagall’s badness rather than, say, Stephen Spender’s badness, so captivating?

Bad poetry can tell you something about the good sort. So McGonagall’s work bears serious investigation. There are, I think, two factors to his immortal unsuccess. One is his unfailing tin ear. He can’t count syllables. By the law of averages, most bad poets will produce a regular line or two by accident. Not McGonagall. Take the famous opening stanza of his worst and therefore most celebrated poem, ‘The Great Tay Bridge Disaster’:

Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay!

Alas! I am very sorry to say

That ninety lives have been taken away

On the last Sabbath day of 1879,

Which will be remember’d for a very long time.

Here is the echt McGonagall. The way the lines clatter towards those thumping masculine rhymes; the way the stresses yank the rhythm off; and a complete collapse into prose in the overlong final line. It’s a sort of anti-genius. You read it with utter delight.

Or look, perhaps, at his excursion into Wordsworthian landscape lyric, describing how:

The chain of mountains there is most frightful to see,

Along each side of the Spittal o’ Glenshee;

but the Castleton o’ Braemar is most beautiful to see,

With its handsome whitewashed homes, and romantic scenery,

And bleak-looking mountains, capped with snow,

Where the deer and the roe do ramble to and fro

Near by the dark river Dee,

Which is most beautiful to see.

To be bad at poetry is to compete in a crowded field. So why does McGonagall come out on top?

Marvel, if you will, at the way the bald repetition of ‘…to see’ manages to be dwindlingly rather than risingly emphatic. Note the clunking internal rhyme of ‘roe’ and ‘fro’; the requirement for the stress on ‘scenery’ to fall on the last syllable; the exquisitely awful variation in line length; the weakness of ‘bleak-looking’ rather than just ‘bleak’; the tell-don’t-show reference to ‘romantic scenery’. You may not like it, but this is what peak performance looks like.

His other great distinction, which is both endearing and hilarious, is tonal: bathos. He is extremely earnest about his calling. He really does think he’s a good poet. Good poets, by the way, can use bathos and broken scansion too: Stevie Smith was one. But Stevie Smith was self-aware in a way McGonagall was not.

Nevertheless, he thrives. The edition of his Poetic Gems I have on my shelves is a mass-market paperback from 1971. Its copy-right page reports that the text was first published in two parts in 1890 and first published as one volume in 1934, before listing only the most recent impressions – 1954, 1955, 1958, 1960, 1961, 1963, 1964 and 1966. He remains in print – Amazon has an edition of his work published in 2023.

McGonagall was what might now be called an ‘outsider artist’. An autodidact, his formal education was over by the time he was seven and he was apprenticed in Dundee as a handloom weaver. He read Shakespeare in his spare time and persuaded his colleagues to subscribe to pay a theatre owner to allow him to star in a production of Macbeth. He passes over without comment, in his memoir, the oddity that the actor paid the theatre to appear, rather than vice versa. He also believed the actor playing Macduff was trying to upstage him and refused to die in his final scene. Macduff was forced, finally, to cast his sword aside and – closing the tragedy in what one critic called ‘a rather undignified way’ – wrestle Macbeth to the ground.

McGonagall discovered his true calling in the summer of 1877, ‘during the Dundee holiday week’, in a rapturous epiphany: ‘A flame, as Lord Byron has said, seemed to kindle up my entire frame, along with a strong desire to write poetry… It was so strong, I imagined that a pen was in my right hand, and a voice crying “Write! Write!”’

Write he did. Not only did he memorialise epochal local events – the sighting of a whale; the Battle of Bannockburn – but he turned his pen, too, to romantic balladry:

I’m a rattling boy from Dublin town,

I courted a girl called Biddy Brown,

Her eyes they were as black as sloes,

She had black hair and an aquiline nose.

Whack fal de da, fal de darelido,

Whack fal de da, fal de darelay,

Whack fal de da, fal de darelido,

Whack fal de da, fal de darelay.

In 1891, three students from Glasgow wrote to the great man enclosing an ode they had written in his honour. It concluded:

They will one day yet rear him monuments of brass, and weep upon his grave,

Though when he was living they would hardly have given him the price of a shave;

But his peerless, priceless “Poetic Gems” will settle once for all

The claim to immortality of William McGonagall.

Comments