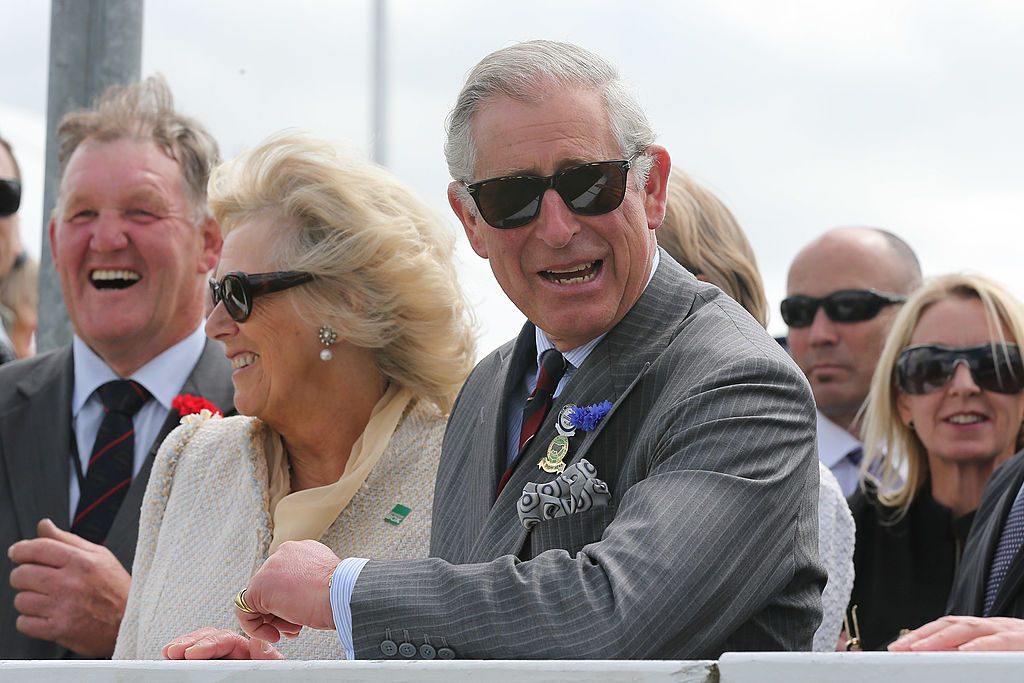

When imagining a monarch’s wardrobe, what comes to mind? With the late Queen, it was bold-coloured dresses (as she famously said, ‘I have to be seen to be believed’), elaborate hats, silk headscarves and those black Launer handbags. Our new King is no less a style icon. For him it’s well-tailored double-breasted suits from Anderson & Sheppard (probably well-worn, for His Majesty is a great advocate of make do and mend – the suit he wore to Harry and Meghan’s wedding was 34 years old), Turnbull & Asser shirts, hats from Lock & Co. and probably the odd tartan kilt.

But it is his collection of pocket squares that I would be most interested to see if ever allowed a peek into the King’s cupboard. He is the world’s most high-profile flagbearer for this quintessential piece of men’s tailoring. And he can in fact lay claim to continuing a tradition established by one of his direct predecessors – for the pocket handkerchief is widely believed to have been invented by Richard II.

How to wear it? First things first, a clarification. Handkerchiefs are not the same as pocket squares. As some say: one for blow, one for show. Yes, you can technically use a regular white (preferably clean) cotton handkerchief as a basic pocket square, but you must remember not to mop your runny nose with it while on show (though I admit to sometimes plucking even my most elaborate pocket squares from my breast to clean my spectacles when the need arises).

Handkerchiefs are not the same as pocket squares. As some say: one for blow, one for show

For material, silk is generally best, although cotton, wool and even linen pocket squares have their place. Silk is perfect for puff folds, but ill-suited to structured folds for which cotton and wool are better. Closely related to the question of material is the type of edge, as this is frequently the most visible part of the whole accessory. The very finest pocket squares often have hand-rolled and hand-stitched edges. Mostly you’ll find machine-rolled edges but, even here, ‘parallel’, ‘Z-shaped’ or ‘embroidery’ edging all carry subtle distinctions.

As for pattern and colour, the possibilities are endless. Single block colours are I think best avoided unless it’s plain white with a dinner jacket. Whatever the style, as the legendary tailor Edward Sexton – co-founder of Nutters and now proprietor of his eponymous business at 35 Savile Row – told me, a pocket square ‘adds a bit of colour and flow to something quite structured’.

There are numerous types of fold. James Bond usually goes for the classic fold, which carries all the restraint required by so cool a cucumber. I asked Matt Spaiser, co-author of From Tailors with Love: An Evolution of Menswear Through the Bond Films, for his view: ‘Some men think a suit is incomplete without a pocket square, while others find them unnecessarily fussy. Bond has been a member of both camps throughout the film series, though Fleming’s literary character belonged to the latter,’ he says. Then there is the understated elegance of the shell or scallop folds, the foppish flamboyance of the upside-down puff or the ostentation of the angel’s peak. As another pocket square aficionado, Thomas Felix Creighton, told me: ‘When puffed, it can add a je ne sais quoi joviality to a lounge suit. Going tie-less in the heat of the Med or the Tropics, it can make a lightweight linen suit look less bare.’

But unlike the necktie, which has rules around knots that would delight a Scout master, the pocket square is a more laissez-faire accessory. You don’t really need to follow any of the formal folds: just pop it into your pocket with theatrical flourish, remembering it’s an iceberg – only about 10 to 20 per cent ever shows – and see how it looks. Your watch word should be sprezzatura: do as Regency-era fashionista Beau Brummell did and jig it around for as much time as you have to waste in front of a mirror to get it just so. But remember to emerge looking like it has taken no effort at all. Sexton recommends it should look ‘rich and flowing, not too stiff or contrived. You take the centre and push it deep into the breast pocket and allow the corners to flow freely, with minimal arranging’. Just sometimes, it is perfect right away and those are the days when you walk to dinner with an extra spring in your step.

Talking of dinner, a word on occasion. If you are monarch of 15 realms you can get away with wearing the pocket square at almost any event. But for the rest of us, pocket squares sadly can feel a bit over the top in the modern workplace. It pains me to surrender to the lowest common denominator logic which looks likely to lead to us all wearing tracksuits to the office in the not too distant future. So I applaud anyone who will hold on to standards and wear one to daily work. But certainly, come evening, there is no easier way to dress up your office-wear for a cocktail party than to embrace this accessory.

The most hazardous vestiary terrain is around matching. You should never identically match your pocket square and your tie (whether a necktie or bowtie). It is a sartorial sin as dire as neckties that stop above one’s bellybutton (unless it’s 1930s-themed fancy dress), brown shoes with a black suit and wearing sandals with socks. (It will not have been lost on the reader that Americans have a habit of doing all of these things.) Rather than matching, the aim should be coordination and complementarity. That is, never match both colour and pattern but a little bit of either in common is fine, indeed often good. Just remember, too much and you’ll be exiled to tailoring Tartarus.

Comments