We are driving in inland New South Wales. We could be driving across grassy English lowland. Wide green hills roll towards a dove-grey horizon, and wisps of white curl down from wet clouds to touch the higher ground. Here and there a stand of trees dots a meadow, and small woods fringe pasture; but there is no forest, nothing dense or dark. Green here is not so much a colour in the artist’s palette as the canvas on which he paints.

The whole aspect is damp, mild, open; and though wire fence strings the roadside and sometimes a lonely track is lined in wooden post-and-rail, the impression is of parkland: of a vast ducal estate, loosely maintained, from which His Grace is unaccountably absent. Small, reedy streams curve their way through shallow basins, and there are turf-edged ponds on grassy inclines where cattle drink. The modest farmsteads, tree-sheltered, may be few, and the human population small, but this announces itself a tamed landscape. Nature’s tooth is herbivorous, her claw clipped: a ruminant and not a predatory world.

And it is raining. For days it has been raining. Not the fierce downpour of the tropics, but the temperate splash of a leaking sky, sweeping in slow curtains across the hills. Small raindrops sting the puddles. Branches dip, leaves drip. Our tyres hiss across wet tarmac. The effect, so soft, so gentle, so English, is not so much of mist as of blur: a perspective that as you lift your eyes to the horizon yields from pale green to the palest grey. Cloud and hilltop kiss damply. The edges of things swim.

Such a landscape, surely, can be nothing but temperate; nothing but benign.

It is easy to see how the early white settlers were fooled by Australia. What is there in this scene to warn you how savagely the seasons change, and with what fickle disregard for the rhythms of land husbandry? There are seasons here, but not as Vivaldi knew them. Perhaps there is a pattern, but it is mysterious: not neatly compartmentalised within the calendar, but a jagged asymmetry running, when it likes, into decades.

It is, they say, seven years since much of New South Wales has had a soaking like this. Beneath a watercolour of wet grassland lurks, in crueller oils, the memory of drought and of burning skies. Only the tin blades of wind-pumps, spinning now pointlessly on rusty iron towers as tanks overspill, warn you of a different reality.

Here is an ecology that can regenerate — as if to fool us — almost overnight, throwing a sweet green cloak over its vengefulness. There is a desert in this mirage.

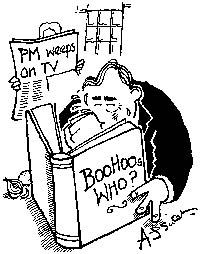

‘Magic Rain Falls Across State’ says the headline in our local paper. If so, we arrived with the magic, landing in a storm at Sydney — and will be departing with it too, for brighter skies are coming, though we must go.

But I don’t mind the rain. Since first seeing Australia (it was raining then too, at night, in Perth) I’ve been fascinated by a sense of the trickery of this immense island. There is something of Prospero’s kingdom here: but a kingdom where the spirits have not quite been brought under control.

Of all the species, humans have the most troubled, the most competitive relationship with the planet that bred them. We are of nature, but we fight it, stand sometimes apart from it, fall in and out of love with it, debate with ourselves whether we really like it at all.

And whether it likes us. There are islands, continents, mountains whose spirit is subversive. I’m no mystic — or not usually — but I cannot ignore persistent intimations of friendliness or hostility from landscapes. To say so is to remark on something different from the danger or difficulty an environment may promise. That’s a practical question. You don’t go into the Sahara without water, but I’ve never found the Sahara unfriendly: it hides nothing, it is what it appears, and lovely in its way. The waterless grey wastes of the central Asian deserts have their own honesty, wearing their stony hearts on their sleeve: ‘Keep out’, they say. The Australian bush says ‘Come in’ — and then it breaks your heart.

America, for all its natural wealth and diverse ecology, feels tabula rasa to me: a slate on which humans could write what they chose. Australia dares you to try. Surpassingly beautiful at so many points and in so many lights, Australia, a continent with which it would be possible to have a deep but never an untormented relationship, is so much more complicated.

Africa, the continent I know best, contains greater dangers than you will find almost anywhere on earth. Africa’s mountains are higher, its deserts as forbidding and its forests more immense than Australia’s. Africa’s wild animals are bigger and scarier, its diseases legion, its fevers prodigious in their menace and variety, and its insects bite. Yet there is something about Africa’s relationship with humans that is comfortable, at ease. Vulnerable as we are, Africa feels like a place where humans nest, and always have, and should.

The hot African night is long, black and velvety: the scream of jackals tingles the spine; and there are places where you know you are not safe. But there is nothing edgy in the darkness. It enfolds you. This is land and landscape that squares with you from the start. Africa isn’t against you, or for you either. Pitiless but not malevolent, Africa doesn’t care if you suffer but nor do the spirits of the place crow. In Australia, as the soft-appearing spinifex grass pierces you, you can almost hear the spirits cackle.

Here, wrote D.H. Lawrence in that strange, shapeless, fitfully tedious but neglected masterpiece of a novel, Kangaroo, there was no animal fear: ‘only sometimes a grey metaphysical dread’.

Dying in Africa, I would sit beneath a thorn tree and feel a sense of return, of oneness with the continent: of being embraced by the earth. But to die in the Australian bush would be to know you had finally been outsmarted: a kind of expulsion from a place where you had trespassed. Your offering of yourself would have been rejected, and strange birds would laugh.

Matthew Parris is a columnist on the Times.

Comments