Beep-bop. The sound of the supermarket checkout – a noise Morrisons felt the need to mute after the Queen’s death – is made possible by an invention which turns 70 this week: the barcode.

On 7 October 1952, a patent was granted to American inventors Bernard Silver and Norman Woodland. Four years earlier, a shopkeeper in Pennsylvania went to the local university begging for help. He needed a way to get customers through his store quickly because logistics were stopping him meeting demand since typing in product numbers and prices into tills was cumbersome. An electronic system wasn’t possible, said the university. Silver overheard the conversation, set up shop in his parents’ apartment and enlisted Woodland.

Woodland’s eureka moment came when he was on a Miami beach, drawing morse code in the sand. Looking at his dots and dashes, he realised that differing lines or shapes could be used to encode different numbers. His initial design for the barcode, which consisted of concentric circles of varying width, was inspired by his swirls in the sand.

The first attempts at implementation used an ultraviolet ink, but it rubbed off too easily – it would have to be a printed design. It took another two decades before barcodes gained commercial success in supermarkets. In the intervening period barcodes did find use on the railways, plastered across freight trains to be scanned by lights and sensors – but huge operating costs soon put a stop to that.

Once laser technology made scanning possible, the codes finally made it into supermarkets when they were unveiled in 1974 in Troy, Ohio. As the store opened, a pack of Wrigley’s chewing gum was the first barcoded item to be scanned – chosen to prove how barcodes worked even on much smaller packaging. Britain’s turn came five years later on a box of Melrose teabags. In 1979 at the Keymarkets supermarket in Lincolnshire, the box was swiped across the scanner and the price popped up on screen.

A reporter interviewed serious-looking shoppers and staff about the invention. The store manager was pleased that it would enable electronic and automatic management of stock levels and ordering – but most importantly it would help ‘control pilferage’.

It wasn’t just store managers who got excited. There is an episode of Tomorrow’s World from 1993 in which it was explained that entomologists were sticking barcodes on the backs of bees to identify individual animals. A musician in Japan attached a signal generator to a barcode scanner so he could make music while doing his shopping. They’ve become crucial in medicine, too.

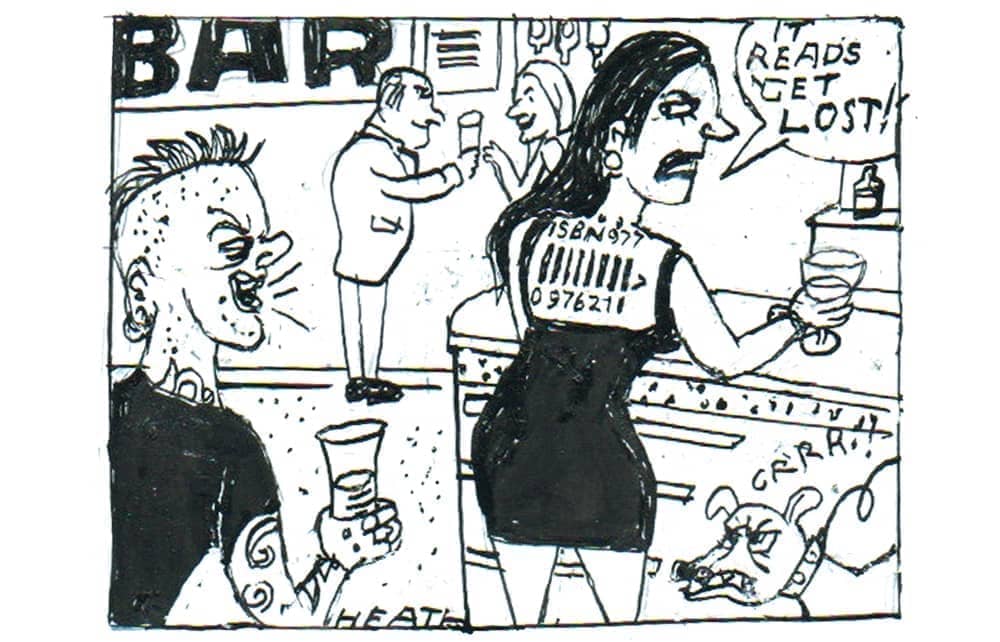

There are billions of possible combinations of codes: the supply is limitless. A 13-digit barcode can be presented ten trillion different ways. That’s enough for everyone on Earth to invent more than 1,200 different products – each with a unique barcode.

It’s easy to forget just how revolutionary barcodes were. Boris Yeltsin wrote that a visit to a Texan supermarket turned him off communism because he was so awed by the ready supply and choice of goods – the shelves packed from front to back. Perhaps that wasn’t just a result of capitalism, but the efficiency of barcodes and the logistical problems they managed to solve.

Comments