In a tour de force of 500 pages of text Simon Sebag Montefiore, historian of Stalin and Potemkin, turns to a totally different subject: the city of Jerusalem. Founded around 1000 BC by Jews on Canaanite foundations, it has been, in turn, capital of the Kingdom of Judah; scene of the crucifixion of Jesus and of Mohammed’s night ride to heaven; a provincial city in the Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, Arab, Ottoman and British empires; and finally the capital of Israel.

Using the latest archaeological evidence, Montefiore recounts with verve the manias and massacres of the different dynasties which ruled the city. The line of David, the blood of the Prophet, the Crusader dynasties of Flanders and Lusignan dominated the city as well as competing religions. Kings were as important as high priests; family trees, as much as articles of belief, determined events.

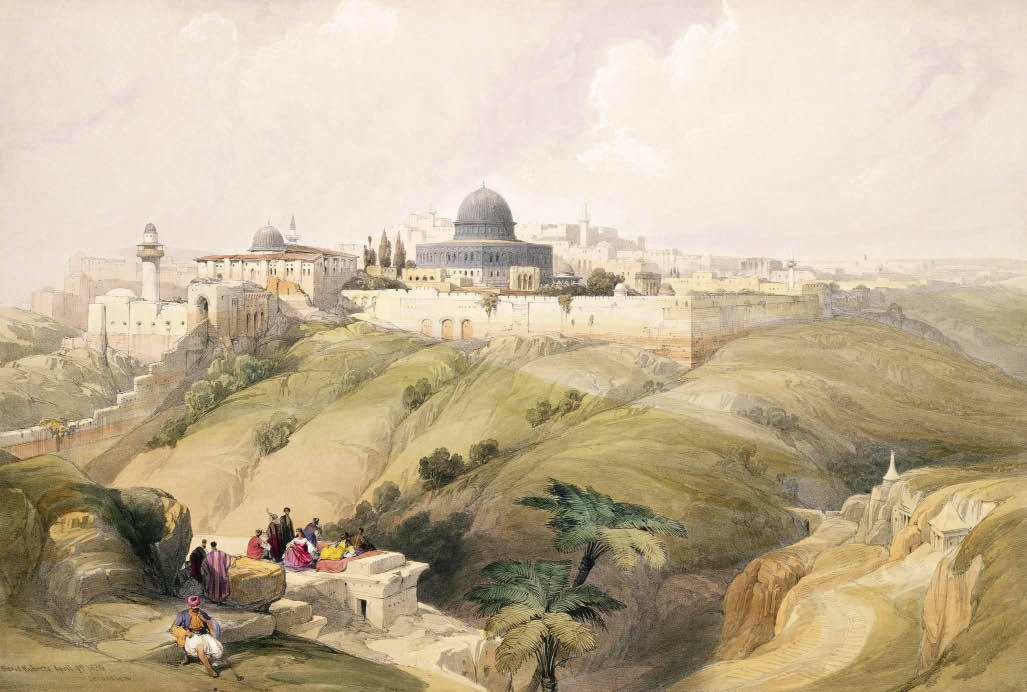

In some of his most original passages Montefiore shows the flexibility of sanctity. In the city sacred to three faiths, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, shrines were shared, traditions invented, when needed. The Dome of the Rock, so different in style and design to other mosques, may have been in part an attempt by early Muslims, strongly influenced by Judaism, to rebuild the Jewish temple and present themselves as the true people of Israel. Montefiore calls it Jerusalem’s defining shrine, the divine esplanade where heaven and earth meet, where God meets man.

His narrative quickens after 1900. Jerusalem again became a battlefield between faiths and empires — and the power-base of Palestinian dynasties like Husseini and Nashashibi. For a time it became a Levantine city. Its mix of races and languages, Arabs, Jews, Armenians and Europeans, was recorded with delight by, among others, the lute-playing party-planner Wassif Jawhariyyeh: extracts from his diary are here published for the first time in England. There were frequent proposals by foreign governments to internationalise the city. As in other Levantine cities, however, in Jerusalem few put loyalty to their city before loyalty to their religion. In 1946 Irgun terrorists blew up the King David Hotel, killing Jews as well Palestinians and the British.

Occasionally Montefiore over-sacralises Jerusalem; it could be a metaphor for piety rather than indispensable to it. Before 1967 few Muslims visited the shrines in the third holiest city of Islam. It is not true, as the former mayor Teddy Kollek is quoted as saying, that everyone has two cities, their own and Jerusalem. Many people prefer the cities of the plain — Alexandria, say, or Paris —to the shining city on the hill. As Montefiore shows, rather than returning to Jerusalem, many Jews preferred to live by the waters of Babylon where some stayed until forced to leave after the creation of Israel in 1948, as related in Iraqi Jewish memoirs like Naïm Kattan’s brilliant Farewell, Babylon. After 300 BC there were growing communities of Jews around the Mediterranean. The kingdom of Israel was only a few centuries older than the diaspora.

Jewish expressions of regret and longing for Jerusalem are eloquent: ‘If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth! . . . One day in Jerusalem is like a thousand days.’ They were literature as well as expressions of reality. Heart-rending laments were also written for another lost paradise, Spain, before the Catholic reconquest.

But many Jews, Montefiore shows, hated, or were indifferent to, their holy city. For Theodor Herzl, one of the founders of Zionism, it represented 2,000 years of inhumanity, intolerance and foulness. The first president of Israel, the brilliant scientist Chaim Weizmann, rarely felt at ease there, and wrote that it was impossible to imagine so much falsehood and blasphemy. Like many Israelis, he preferred Tel Aviv.

Montefiore thinks that the United States and Israel are built on an ideal of freedom touched by the divine: some of their neighbours, and inhabitants, might disagree. The history of Jerusalem, like Israel itself, was determined by power and economics as well as, and perhaps more than, faith and ideology. It was not only a meeting of heaven and earth but also a place to live and work. Israel was created not only by Judaism and Zionism but also, as the author recounts, by the strategic needs and fears of the British empire, as interpreted by Lloyd George and Churchill. The British army helped train part of the future Israel defence forces. Bomber Harris started his career in Palestine, and British bombs helped defeat the Palestinian national movement (apart from their own appalling leaders).

Jerusalem ends on a sad note: one more example of the unhappiness of answered prayers. Far more than the Lebanese of different religious groups in Beirut during their civil war, since the intifada of 1988, Palestinians and Israelis have lived in parallel universes in Jerusalem. They do not work or socialise together and dare not venture into each other’s neighbourhoods; they do not even exchange looks in the street. In parts of the city a state of schizophrenic anxiety prevails. On both sides nationalism appears to be increasingly religious. The city’s fate frequently disrupts Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. The powder keg awaits the match.

Comments