Since no one has bothered to ask what my must-read book of last year was I’m going to tell you here: it’s Matt Ridley’s Evolution of Everything.

I don’t think it has appeared on nearly so many recommended lists as his previous bestsellers Genome and The Rational Optimist, nor has it been so widely reviewed. And I have a strong inkling as to why: its message is so revolutionary as to alienate pretty much everyone across the spectrum, from Christians and Muslims to corporate bosses, historians, feminists, educationalists and conspiracy theorists, from Greens and socialists all the way across (if there’s a difference) to Conservatives like George Osborne and David Cameron.

It also happens to be, in my view, as near as damn it to 100 per cent right about every subject it broaches, from the internet to bankers, from crop circles to education, from the nurture vs nature debate to religion. And no one likes a smart arse — especially not when he’s an Eton-educated smart arse with a title, an estate (built on coal-mining) and an unfortunate reputation as the man who was chairman of Northern Rock when it had to be bailed out by the taxpayer — do they?

What I find almost more interesting than the book, though, is the way it has been reviewed by those of a bien-pensant persuasion — most notably John Gray in the Guardian. He hated it. So much so, it’s pretty clear to me, that he couldn’t even bring himself to read it. Or if he did read it, he was so consumed by righteous rage that he couldn’t bring himself to address any of the utterly disgusting points made in the book.

There’s lots of invective and lofty contempt: ‘bumptious and tediously repetitive tract’; ‘if he was a more serious and reflective writer, Ridley might…’ [‘if he were’, surely?]; ‘a dated and mechanical version of right-wing libertarianism’. Plus, there’s a whole paragraph of ad homs, majoring on Eton, titles and Northern Rock. Precious little on what the book actually says.

Basically, what it says is that evolution is a phenomenon which extends far beyond Darwin to embrace absolutely every-thing. The internet, for example. No one planned it. No one — pace Al Gore and Tim Berners Lee — strictly invented it. It just sprang up, driven by consumer need and made possible by available technology. As Ridley says: ‘It is a living example, before our eyes, of the phenomenon of evolutionary emergence — of complexity and order spontaneously created in a decentralised fashion without a designer.’

Which is what, of course, is such anathema to control freaks everywhere, from the Chinese, Iranian and Russian regimes to Barack Obama, who famously declared in 2012: ‘The internet didn’t get invented on its own. Government research created the internet.’

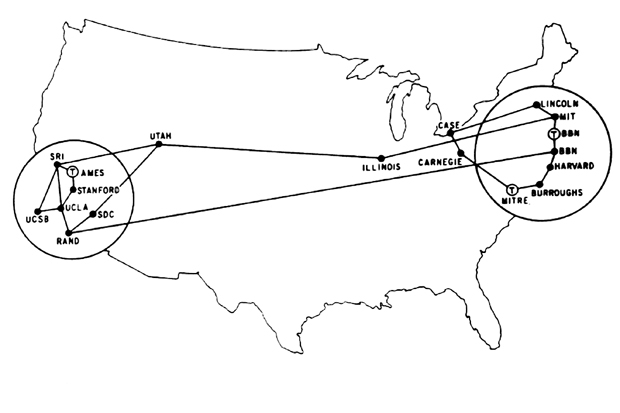

This claim, as Ridley demonstrates, is at best moot, at worst flat-out untrue. In fact, government was actually responsible for postponing the internet. One of its early forms was the Pentagon-funded Arpanet, which until 1989 was prohibited for private or commercial purposes. An MIT handbook in the 1980s reminded users: ‘sending electronic messages over the ARPAnet for commercial profit or political purposes is both antisocial and illegal’. Only after it was effectively privatised in the 1990s did the internet take off.

Similar rules apply to hydraulic fracturing (aka ‘fracking’), another technology often ascribed to government-sponsored R&D. According to a meme disseminated by California’s Breakthrough Institute, it was based on microseismic imaging technology developed at the federal Sandia National Laboratory. Hmm. Up to a point. Ridley has done some digging and found that the actual funding for this research came from the entirely privately funded Gas Research Institute, which hired a technician from Sandia. ‘So the only federal involvement was to provide a space in which to work.’

You can be sure, though, that the false meme will persist, because it suits the narrative which so many of us prefer to believe — that without direction from on high, nothing would ever get done. In its rawest form, this is the impulse that has, throughout history, led mankind to ascribe events to deities — whether it’s Aztecs cutting out the beating hearts of prisoners to boost their harvests, or modern governments ordering that hilltops be transformed into industrial wind Golgothas to appease Gaia. But you also find it everywhere from the Great Men theory championed by many historians to the way companies’ share prices rise or fall when they get a new CEO.

It all stems, I fear, from an innate mistrust so many of us have of the unutterable amazingness of our own species. Personally, I’ve long believed that left largely to our own devices, we will tend to do far more good than harm — if only out of mutual self-interest. But up till now I’ve found it hard to come up with the perfect rebuttal to the line I often hear from those of a less classical liberal persuasion: ‘You don’t like government. So what would you prefer — Somalia?’

Well now, thanks to Ridley, I do have my answer. We’d both of us concede, I’m sure, that there is a place for very limited government. But what the weight of historical evidence shows us overwhelmingly is that almost everything good in the world has sprung up by accident, and almost everything bad is the (largely) unintended consequence of utopians with too much power trying to plan the world into a better state.

From the latter, Ridley notes, we got the: first world war, the Russian Revolution, the Versailles Treaty, the Great Depression, the Nazi regime, the second world war, the Chinese Revolution, the 2008 financial crisis.

From the former, we got the growth of global income, the disappearance of infectious diseases; the clean-up of rivers and air… the use of genetic fingerprinting to convict criminals and acquit the innocent.

Yet still our entire global system is geared towards top-down directives that invariably make things worse. We never learn, do we?

Comments