‘Does history repeat itself, the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce?’ asked Julian Barnes in A History of the World in 10½ Chapters. ‘No, that’s too grand, too considered a process. History just burps, and we taste again that raw-onion sandwich it swallowed centuries ago.’ Reading David Kynaston’s densely detailed new book — in a ‘projected sequence of books about Britain between 1945 and 1979’ with the slightly magniloquent general title of Tales of a New Jerusalem — there isn’t half a whiff of onions.

We have an Old Etonian prime minister with a chancellor ideologically hellbent on belt-tightening; we have a poisonous and sometimes violent debate about immigration; we have fears about the consequences for the national moral character if homosexuals are accorded equal rights; we have a national epidemic of hand-wringing about selective education; we have a political class dismayed that young people don’t seem to give a toss about politics (‘Western Germany, steel nationalisation, the constitutional future of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, the Singapore Elections’, reported an unbelieving advisory committee, ‘nearly all of them seem incapable of the slightest interest in, let alone enthusiasm for, any of these topics’).

We also have mail-order shopping starting to eat into high-street sales; and we have a new entertainment medium that appears to spell doom for established formats (variety theatres closing down; cinema attendances in the doldrums; fears for electoral turnout: ‘What will the one-eyed monster devour next?’). Plus, these at least appearing to be immutable laws of nature, we have Bruce Forsyth on the telly of an evening and the bien-pensants of Hampstead getting their balls in an uproar about a burger joint opening.

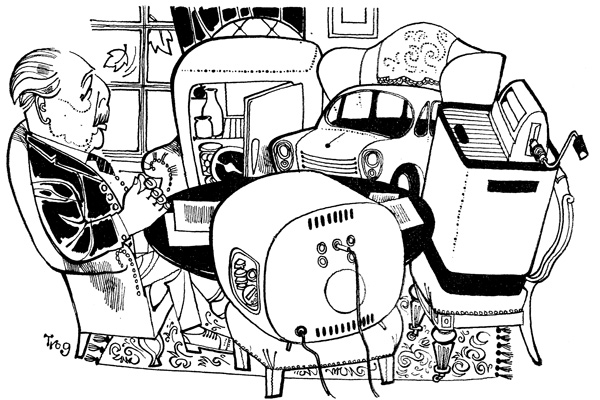

The short period to which Kynaston addresses himself here, however, is more than just a foreshadowing. It is where the social order we recognise now — the consumer society, if you like — begins to get going. As he’s careful to note, the penetration of consumer durables into the average UK household was at this stage a steady trickle rather than a flood, the postwar make-do-and-mend culture continued to dominate, and supermarkets as yet were very far from ubiquitous. But after the Conservative victory in the 1959 general election, The Spectator was able to carry a Trog cartoon (opposite) ‘showing Macmillan sitting in best Edwardian manner, facing an array of consumer durables’.

Sterling became fully convertible, hire-purchase controls were removed, rent controls were relaxed; transatlantic passenger jets began and the subscriber trunk dialling system — allowing you to make a telephone call without operator assistance — was established. Amazing the number of other debuts in national life this short period saw: Little Chef, eye-level grills, biros, the Mini, the Today programme, Women’s Realm, Bunty, Which?, Blue Peter, Noggin the Nog and Judi Dench — whom the critics judged ‘goes mad quite nicely’ as Ophelia.

It was TTFN, on the other hand, to Queen Charlotte’s Ball. Was meritocracy on its way? Kind of. Certainly, a startling checklist of the working-class and grammar-school boys (most were boys, of course) entering public life emerges: Dennis Potter, Robert Robinson, Harold Evans, Brian Redhead, Malcolm Bradbury, Melvyn Bragg, Jean Rook, B.S. Johnson, Keith Waterhouse, John Carey, Ian Hamilton, Tony Richardson, Don McCullin, Peter Hall, Terence Donovan, David Bailey, Zandra Rhodes and Lionel Bart.

Even high Tories felt the warm wind of egalitarianism blow. A former Tory MP, Christopher Hollis, wrote in the Spectator:

I think the time has come when it would be to the advantage of the nation that the Conservative party should be somewhat less ‘U’ in its higher personnel and when a party which pays lip-service to equality of opportunity should in practice treat at least (shall we say?) a Rugbeian as the equal of an Etonian.

The two big themes of this volume, in terms of public policy, feed directly into these questions of class mobility and consumer society: education and housing. This is a period of massive slum clearances and the building of giant new modernist schemes — very often without bothering to ask the opinions of those who would be rehoused, many of whom rather preferred their slums. One young architect, touring brand-new Corbusier-style highrise flats in Roehampton, was horrified by what the first tenants had done by way of decoration:

The windows were covered with dainty net curtains, the walls were covered with pink cut-glass mirrors and ‘kitsch’, and the furniture comprised ugly three-piece suites, not even the clean forms of wartime Utility furniture.

How very dare they!

We have here some really good and chewy stuff, too, on the debate over grammar schools and comprehensives, both within the Left and across the political spectrum. The debate, it turns out, has barely changed. Kynaston is a historian who likes to get out of the way. You seldom read a decisive judgment or a grand-sweep generalisation. Rather, he rummages in the attic and pulls a whole clattering cavalcade of interesting junk down on himself: details in more or less chronological order, retailed in a telegraphic style that reminded me of this magazine’s Portrait of the Week. Sometimes — as you zing from Doris Bonkers’s seaside holiday to a Sunday League football result and thence to a discussion of economic policy via an itemisation of what was on telly that weekend — you find yourself wanting him to pull focus a bit. But here — which is the point — is the texture of life as it was lived.

The jacket quotes a passage from late in the book that is an extreme but far from unique instance of the clattering cavalcade style. I wasn’t even alive then but I still feel nostalgic:

Galaxy, Picnic, Caramac (‘Smooth as chocolate … tasty as toffee … yet it’s new all through!’), Knorr Instant Cubes, Bettaloaf, Nimble, New Zealand Cheddar (‘Now I’m sure they’ll grow up firm and strong’), Jacob’s Rose Cream Marshmallow Biscuits, Sifta Table Salt (‘Six Gay Colours’), Player’s Bachelor Tipped, Rothmans King Size, wipe-clean surfaces, Sqezy (‘In the easy squeezy pack’), coloured Lux (‘four heavenly pastel shades of blue, pink, green and yellow, as well as your favourite white’), Fairy Snow, new Tide with double-action Bluinite, Persil (‘washes whiter — more safely’), Nylon, Terylene, Orlon, Acrilan, Tricel, Daks skirts, Jaeger girls, ‘U’ bra by Silhouette (‘Gives You the Look that He Admires’), Body Mist, Mum Rollette, Odo-ro-no, Twink (‘The Home Perm that Really Lasts’), Pakamac, Hotpoint Pacemaker, Pye Portable, Philips Philishave, ‘Get Up To Date — Go Electric!’

Threaded through the facts and figures are the voices of diarists, letter-writers, Mass Observation interviewees and so forth, and Kynaston makes great use of these sources. Lorna Sage, Richard Crossman, John Fowles, Kenneth Williams and many others pop up repeatedly and enliveningly. Among his many virtues are his thoroughness (when he’s quoting Larkin, for instance, he’s gone through the unpublished material as well as the Letters to Monica) and attention to detail. He notices, for instance, when the FT’s front-page graphic of the globe acquires a whimsical Sputnik for a few days; and he keeps a close eye, through his text, on the fortunes of Bronco toilet paper. You rejoice with him to see Bronco’s coloured range ‘successfully going national, with pink the most popular, followed by blue and green’.

We really never had had it so good. Except for Philip Larkin, of course, who never had it good at all. Here he is, early on, with all this zinging modernity to look forward to:

An utterly lonely Sunday, spent indoors except for the usual excursion to the pillar box. I have sat doing nothing since about 4 o’clock, & am now slightly drunk on rum and honey & hot water. The usual revolting insufficient meals – an awful tinned steak pudding, like eating a hot poultice, & sausages. I can’t ever remember being so dead since about 1947.

Comments