I am a priest in the high church tradition of the Church of England. The technical term is Anglo-Catholicism, but I come from a very different Christian background. My heritage is non-conformist evangelical – I was baptised in a swimming pool in the summer of my first year of university.

St James’s in Piccadilly hosts events featuring ‘icons’ from RuPaul’s Drag Race UK

It’s a long story as to how I’ve ended up wearing a chasuble and celebrating ‘Mass’, but a big part of it has been to do with church architecture. After several years in the charismatic evangelical scene, I became fascinated with the beauty of medieval churches, particularly cathedrals. I began to think of the large white-cuboid former bingo hall owned by our church as soulless and empty. I thought it was a shame that it was rented out for conferences of police or social workers during the week. Wouldn’t it be rather nice if it were reserved exclusively for worship? I didn’t use the phrase ‘sacred space’ but, looking back, I can see that that is exactly what I was yearning for.

When I was transitioning to a high-church Anglo-Catholic, I got a job working as a verger in a cathedral that had excited my imagination some years before. The aesthetic was, of course, very different but I found that some of the issues that had exercised me in my low-church days were still present. It seemed that the building’s beauty and tranquillity were disturbed by the uses to which it was put. Part of my job was to erect and disassemble the huge staging apparatus for the hosting of classical concerts that took place on at least a weekly basis. I vividly remember an event called ‘Space for Peace’: a multi-faith gathering in which various groups were invited to set up in particular areas of the cathedral and conduct chants, songs and prayers in the idiom of their different religions. The cross-pollination of musical and spiritual registers created, to my untrained ear, not so much harmony as an abrasive cacophony.

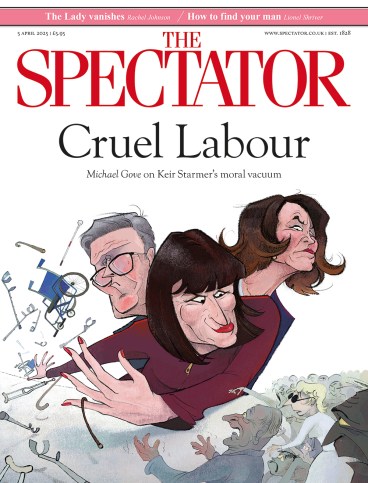

But my experiences were nothing compared with some of the spiritually hollow events held in cathedrals in recent years: a 55ft helter-skelter in the nave at Norwich; miniature golf in the nave at Rochester; lunar installations and planetary displays in Ely, Derby and Liverpool; gin promotion in Blackburn; fashion shows at St Paul’s; silent discos in Canterbury, St Albans, Hereford and others; yoga classes in York Minster. Several historic parish churches have suffered similar embarrassments. Some, like St James, West Hampstead, have been turned into commercial soft-play areas. The notoriously progressive St James’s in Piccadilly has staged ‘eco-contemplative’ services and ‘Preach!’ nights featuring ‘RuPaul’s Drag Race UK icons River Medway and Veronica Green’.

Why has the Church of England suffered such a loss of confidence in identity when it comes to these buildings? I’ve become convinced that the C of E has, to a great degree, transformed into an expression of a secularised form of Christianity – and that the examples I’ve given are indicative of the fact.

The great phenomenologist of religion Mircea Eliade argued that human beings are naturally religious. It is only in the past few centuries in the West that non-religious man has come to the fore, but he is a historical outlier. One of the things that I’ve learned from Eliade is that we non-religious modern people (and we all fit into this category to some extent because of our social conditioning) have a very different way of experiencing space and time from our religious forebears. For them, there were sacred and profane times and spaces, with sacred space in particular providing a special point of connection between the human and the divine. These spaces – churches, temples, sacred groves and so on – have existed for all people until relatively recently. They are, symbolically speaking, axis mundi, or centres of the world. They allow human beings to orientate themselves.

These days, man has no understanding of either hierarchical space or time. It’s all just one damn thing, or place, after another. Without distinction, everything is crushed under an oppressive homogeneity.

But the thing about non-religious man is that he’s really still religious at heart. We can see this in all sorts of ways. Some are mundane, such as the marking of birthdays or the visiting of places of particular personal significance. The philosopher Charles Taylor calls these things ‘subtler languages’ because they are attempts to access the transcendent dimension of religion without committing to traditional doctrines, dogmas or practices.

And this is where the C of E gets it badly wrong when it comes to buildings. I was speaking to a friend recently who’s come back to England from America. He’d been working with young people in an evangelical Christian setting and two things he said struck me. Firstly, young people are increasingly uninterested in questions of truth or falsity – they care more about notions of meaning and value. Secondly (with no offence intended to US readers), America is, well, much uglier than Britain. Everywhere, he said, is a car park with a concrete building next to it.

People today, then, are caring less and less about whether or not Christianity is true, and more about how to find meaning and live a good life. In other words, the Church will struggle to engage people on a purely cognitive level. It needs to aim at the heart. And the way to the heart is beauty.

The C of E should have a unique advantage in the form of our historic churches and cathedrals. These are places that have marked rites of passage for generations, where sacraments have been celebrated and where, as T.S. Eliot put it in ‘Little Gidding’, ‘prayer has been valid’.

The C of E should remember that the world needs the sacred. It needs actual churches and cathedrals, places of holiness, peace, prayer, signs of God and of the transcendent realm. It does not need another rave in the nave.

Jamie Franklin discusses how to improve the Church of England with Quentin Letts on the latest Edition podcast from The Spectator:

Comments