In January 1559 an Italian envoy wrote of Elizabeth I’s coronation that ‘they are preparing for [the ceremony] and work both day and night’. More than four and a half centuries later much the same could be said of the imminent investiture of Charles III – an event overshadowed, at the time of writing, by the uncertainty as to whether his publicity-shy younger son and wilting violet of a wife will be attending. But, as Ian Lloyd describes in The Throne, there have been many more dramatic build-ups to coronations, some culminating in injury or even death.

James I hired 500 soldiers as a personal bodyguard to shield him against ‘any tumults and disorder’

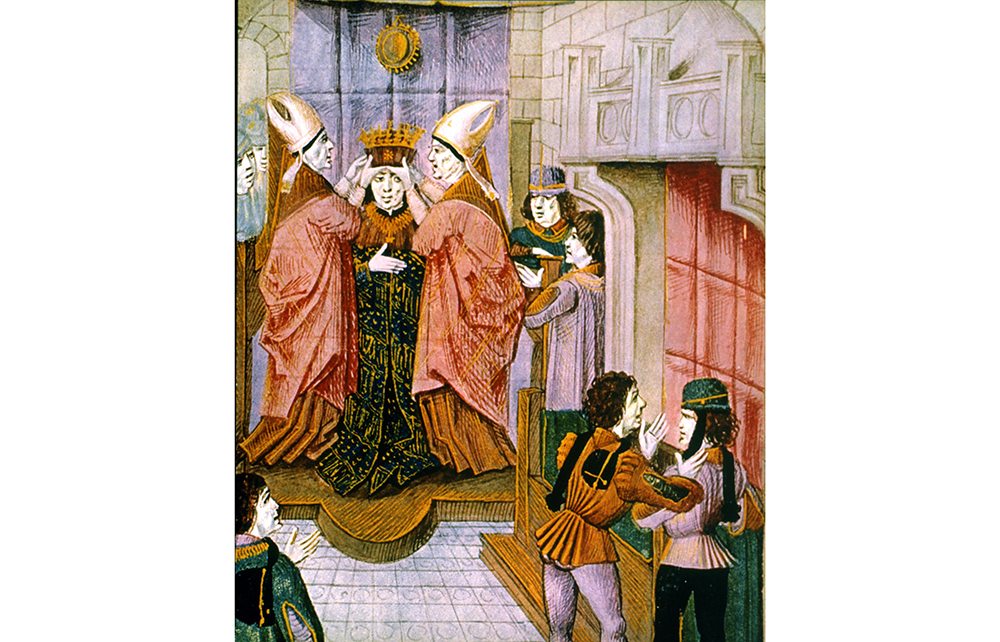

The scene is set in this brisk, gossipy history by William the Conqueror’s crowning, which took place at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day, just two months after the Battle of Hastings – William’s hurry stemming from fear that his claim would be challenged. So tense was the atmosphere, the ceremony was interrupted by a guard torching nearby buildings after hearing noises of celebration, which he assumed to be a riot – meaning that the king’s consecration had to be completed amid looting and mass panic.

The first coronation for which any detailed records exist, Richard I’s on 3 September 1189, suffered from the bad omen of a bat fluttering around the throne – which was apparently borne out by the arrival of group of Jews bearing gifts for the new king. They were barred, and anti-Semitic riots erupted throughout the country. Centuries later, the same uneasiness prevailed at Mary Tudor’s coronation, her surly mood caused by fear of anti-Catholic rioting. In 1603, the paranoid James I hired 500 soldiers as a personal bodyguard to shield him against ‘any tumults and disorder’.

But not all monarchs regarded their investitures so grimly. King John displayed ‘unseemly levity’ at his, and left before receiving the sacrament. William IV requested a ‘short and cheap’ ceremony – soon dubbed the ‘penny coronation’ and ‘half crown-ation’. Despite costing £43,159, it was a fraction of the sum his extravagant brother George IV lavished on his own affair, which amounted to £238,000.

In 40 short chapters, depicting 38 coronations, and two (for Edward V and Edward VIII) which were planned but never took place, Lloyd offers many amusing anecdotes. We learn that Edward II’s was masterminded by Piers Gaveston, the king’s lover, who arrived, according to one chronicler, ‘so decked out that he more resembled the god Mars than an ordinary mortal’. But his powers of organisation failed to match his sartorial flair: part of a wall collapsed during the event, killing a knight, and the banquet was delayed so long that the food was all but inedible when it arrived.

Lloyd relishes the human details. A joust to celebrate Elizabeth I’s coronation was postponed, as the queen was ‘feeling rather tired’ – and much the same problem was apparent when Charles II was crowned in 1661. Samuel Pepys, after too many toasts to the monarch’s health, ‘waked in the morning with my head in a sad taking through the last night’s drink’. The chaos at Victoria’s unrehearsed coronation was increased by an incompetent Archbishop of Canterbury, champagne-drinking peers with their coronets askew and guests rolling down staircases owing to infirmity. But Lord Melbourne had assured her that ‘you’ll like it when you’re there’ – and she would describe the day as ‘the proudest of my life’.

Though Lloyd’s colloquial tone can grate (one king is described as looking ‘like death warmed up’, and an altar piece as ‘humongous’), The Throne is good fun. But amid the accounts of which animals were eaten at which banquets, and which vehicle conveyed which monarch to the ceremony (with a running joke on the miseries of travelling in the notoriously uncomfortable gold state coach), there’s not much reflection about the wider symbolic purpose of it all. One of the credited sources is Roy Strong’s magisterial Coronation (2005), which gave the subject real weight and depth. Lloyd’s clearly hastily written book will divert for a few hours, but is unlikely to linger in the memory.

Comments