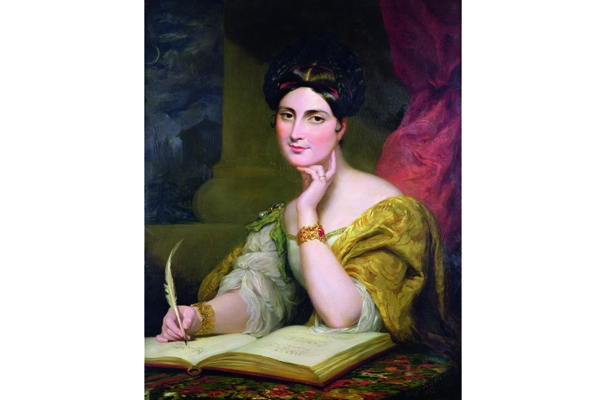

Caroline Norton seems an unlikely pioneer of women’s rights. Born in 1808, the granddaughter of the playwright Sheridan, she was a black-eyed beauty, a sharp-tongued socialite with a gift for writing. She matters today because she quarrelled with her husband and refused to put up and shut up. That quarrel is the subject of Diane Atkinson’s book.

Caroline and her two beautiful sisters were brought up in genteel poverty by their widowed mother in a grace-and-favour apartment at Hampton Court. Lack of money meant that when Caroline was 19 she was married off to the first eligible man who came along.

George Norton, her husband, was the younger brother and heir to a childless peer named Lord Grantley. George was neither so pretty nor so witty as Caroline. He was a Tory, she was a Whig. Caroline mimicked George, snubbed him in front of her smart friends and showed off. An outrageous flirt, she became a favourite of the handsome fifty-something Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne. George was angry and resentful. When they argued, he hit her, usually after he had been drinking.

In 1836 after a violent quarrel, George shut Caroline out of the house and refused to allow her to see their three sons. Atkinson makes plain that George was manipulated by Lord Grantley, a mean-minded curmudgeon with a litigation habit. It was Grantley who whispered in George’s ear that Caroline was having an affair with Lord Melbourne.

Whether Caroline was in fact Melbourne’s mistress remains unproven. Both strenuously denied it. But Atkinson argues convincingly, on the basis of the shared intimacy of their letters, that the relationship was physical, and Caroline certainly claimed that Melbourne was the love of her life.

Egged on by the nasty Grantley, George sued Melbourne for criminal conversation or ‘crim con’ — as adultery was then called — with his wife. For the Tory Nortons, bringing a case against the Prime Minister was a political coup, but it didn’t succeed. Ably defended by the Whig lawyer John Campbell (a man ‘as thickset as a navvy and as hard as nails’), Melbourne was acquitted.

Caroline was declared innocent of adultery. But her life was ruined. She was socially disgraced. As the law then stood, she was unable to divorce her husband, nor could he divorce her, and he refused to allow her access to their three sons.

Undaunted, Caroline set about changing the law. This is the heroic part of her story. Largely thanks to her pamphlets and lobbying, the Infant Custody Bill was passed in 1839, giving estranged wives custody of children under seven. But the act was no help to Caroline, as George had arranged for the children to stay with his family in Scotland, where the new law did not apply. For years, George bullied and tormented her, tempting her with offers of money and access, and endlessly going back on his word.

Not until one of her sons died, aged nine, from tetanus following a fall from his pony was Caroline allowed to see her children. But her victory was a hollow one. Her eldest boy, the sweet-natured Fletcher Norton, died of TB aged 29. The remaining son, Brindley, married an illiterate peasant woman from Capri and seems — from the behaviour detailed here — to have suffered from psychosis, becoming paranoid, depressive and violent.

Diane Atkinson has used the ‘new research’ provided by the internet and digital imaging to locate letters from Caroline Norton in libraries on both sides of the Atlantic, and this has enabled her to construct her story in astonishingly detail. The squabbling between Mr and Mrs Norton doesn’t always make for an entertaining read as, like most marital conflicts, it goes over and over the same old ground. But Atkinson does a brilliant job in showing exactly what her subject’s life was like.

Caroline Norton was not a feminist. She did not believe that women were equal to men. She fought, as this book makes clear, for justice for women, not equality. But Atkinson is surely right to see the tigress Norton as ‘a heroine to every woman who has made a mistake in judging a man’.

Comments