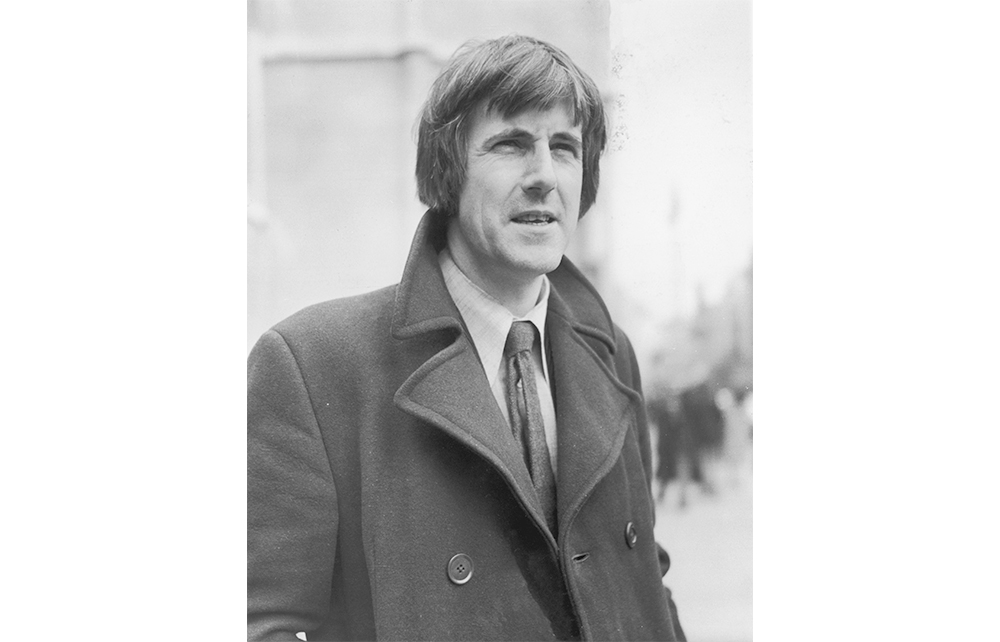

‘The politics of Paul Foot are an extraordinary mixture of first-class reporting, primitive Marxism, family wit and fantasy.’ This judgment is taken from a review of Foot’s first book, The Politics of Harold Wilson (1968). The reviewer was well placed to assess it, and, according to this biography, he ‘tore the book apart’. As well as being an MP, he was Paul’s uncle, Michael Foot.

Born in 1937, Paul Foot came from a political family. His grandfather, Isaac, and his eldest uncle, Dingle, were both Liberal MPs; his father, Hugh, was a distinguished diplomat who, as Lord Caradon, would become a foreign office minister; and his uncle Michael became a cabinet minister and Labour’s next leader but one after Wilson. Perhaps just as significant, they were all bookish, especially Isaac, who was said to possess 2,000 volumes on the French Revolution alone. Michael would describe his father as ‘a bibliophilial drunkard’ – and he should know, as he drank at the same fountain. Paul, too, became addicted to books; his journeys around the country were made longer by detours to remote secondhand bookshops. He developed a special passion for Shelley, whom he saw as a political poet. He wrote his biography, Red Shelley (1981), and lectured about Shelley to coal miners. He bribed his sons to learn ‘The Masque of Anarchy’ by heart.

As a person, Foot was energetic, passionate and fiercely competitive, and exhilarating, life-enhancing company. As a journalist, he was dogged, persistent, good at detail and a friend to the friendless. ‘Footy’ was much admired by his fellow scribes, who twice voted him Journalist of the Year. You might describe him as the conscience of Fleet Street. One of his editors reflected that Foot ‘had the rare ability to make our trade feel noble’. Foot was also fearless. In 1965 he wrote a hostile obituary of Winston Churchill, describing the dead hero as ‘this monstrous, battle-hungry thug’. It was perhaps just as well that he wrote this for an obscure publication called Labour Worker, rather than in his ‘Mandrake’ column for the Sunday Telegraph.

He was a witty writer and a very funny speaker. One of his techniques was to feign lack of understanding. When told that his invitation to talk to schoolboys on ‘the urgent need for socialism in our time’ had to be withdrawn because of an unfortunate clash with another visitor, he affected incomprehension. ‘My enquiries reveal that this other visitor is Her Majesty the Queen. Since I gather she is not speaking on the urgent need for socialism in our time, I cannot understand what all the fuss is about.’

Foot read law at Oxford, where he formed a lifelong friendship with Richard Ingrams. After Ingrams became editor of Private Eye, he invited Foot to write a regular column of investigative journalism for the magazine, ‘Footnotes’, which he would do on and off for the rest of his life, despite being lampooned as the naive radical Dave Spart. After Foot’s death Ingrams would write a memoir of him, My Friend Footy.

One of his editors reflected

that Foot ‘had the rare ability to make our trade seem noble’

Soon after leaving Oxford, Foot fell under the lasting influence of Tony Cliff, who had come to Britain in 1947 from a Jewish family in Palestine. Cliff offered a Trotskyist alternative to Marxists disillusioned with the Soviet Union. He formed a political party, known as the International Socialists and later as the Socialist Workers’ Party. Foot would remain faithful all his life to the doctrine preached by Cliff, though the party never attracted more than a few thousand members, or gained more than a few hundred votes at elections. There was no question that Foot was a zealot. He hated Tories on principle, yet he liked Conservative mavericks such as Alan Clark and indeed Margaret Thatcher. He even got on with Enoch Powell.

In 1972 he joined the tiny staff of the Socialist Worker. The features editor was Christopher Hitchens, who would write many years later:

Working to improve those dour pages brought me into proper contact with Paul Foot. He was somewhat older than me, but his reaction to any injustice was as outraged and appalled as that of any young person who had just discovered that life is unfair.

According to his sister, Foot’s sense of injustice dated from his days as a schoolboy at Shrewsbury, where his housemaster, Anthony Chenevix-Trench, took a perverse pleasure in beating boys, giving them the choice between the more painful cane with trousers on, or the less painful strap with trousers off. Some 40 years later Foot exposed his housemaster’s abuse in an angry piece for the London Review of Books.

For whatever reason, Foot would spend his career as a journalist trying to right wrongs, just as he tried to bring about revolutionary change as an agitator. For him there was no difference: society was unjust, and he would always side with the underdog. But there was a tension in Foot’s life between his politics and his journalism. When approached by the editor of the Daily Mirror to write a column, his first instinct was to refuse: ‘After all, Mike, I am a Trot.’ Mike Molloy persuaded Foot that he would be given the independence he required. Then he named the salary. ‘Oh no, God, no, that’s too much,’ replied Foot. He succumbed when told that this was what the union had fought for, and that if he did not accept it he would be letting down his fellow workers.

This is a well-written, balanced biography. Margaret Renn worked alongside Foot for more than a decade; she is someone Foot would have called a ‘comrade’. If her book is affectionate, that is fitting, because Foot was a man who inspired affection in those who knew him, even in those who thought his politics ‘potty’.

His death at the early age of 66 inspired a joke in Private Eye. ‘RIP Paul Foot 1937-2004. A Great Journalist. Died in time for press day.’

Comments