“In Britain, a free press is non-negotiable,” Ivan Lewis has just said – before suggesting ways that Government might, ahem, oversee

this freedom. The shadow culture secretary has an idea: a register system to license journalists. “As in other professions, the industry should consider whether people guilty of gross

malpractice should be struck off,” he said. He wants “a new system of independent regulation including proper like-for-like redress, which means mistakes and falsehoods on the front

page receive apologies and retraction on the front page”. It’s an odd type of independence: one that would be prescribed by the political elite. And what type of journalists might it

target? I’ve heard ministers complain about the “unethical” and “unprofessional” practices of certain journalists: almost always the ones who cause them the most

problems, like the Andrew Gilligans of this world. Blair’s No. 10 once complained to the BBC about the “John Humphrys problem” – and claimed this was a simple matter of bad

journalism. Certain types of politician have been mulling ways of resolving this “problem” ever since.

“In Britain, a free press is non-negotiable,” Ivan Lewis has just said – before suggesting ways that Government might, ahem, oversee

this freedom. The shadow culture secretary has an idea: a register system to license journalists. “As in other professions, the industry should consider whether people guilty of gross

malpractice should be struck off,” he said. He wants “a new system of independent regulation including proper like-for-like redress, which means mistakes and falsehoods on the front

page receive apologies and retraction on the front page”. It’s an odd type of independence: one that would be prescribed by the political elite. And what type of journalists might it

target? I’ve heard ministers complain about the “unethical” and “unprofessional” practices of certain journalists: almost always the ones who cause them the most

problems, like the Andrew Gilligans of this world. Blair’s No. 10 once complained to the BBC about the “John Humphrys problem” – and claimed this was a simple matter of bad

journalism. Certain types of politician have been mulling ways of resolving this “problem” ever since.

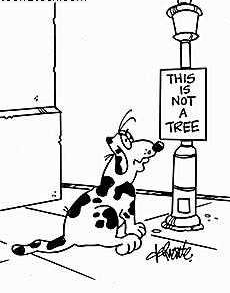

There is a wider, more important issue here: why is this even being raised? Many MPs still have their knives out for the press, after the Daily Telegraph’s comprehensive treatment of the expenses scandal. They are looking at stories of one of their own – Margaret Moran last week, weeping in the dock of a Magistrate’s Court because this pesky free press got hold of her fraudulent expense claims. You’d be surprised how many MPs hold the press collectively responsible for all this, and moan about disrespect. As Jeremy Paxman famously put it, the British press treats politicians with the respect that a dog reserves for a lamppost. This well-drenched lamppost has had enough.

The difference, now, is that the press has become massively vulnerable due to the News of the World hacking scandal and the criminal career of Glenn Mulcaire, a private investigator. The unspeakable measures he took when fishing for stories were so egregious that it closed a newspaper; as my former colleague Ian Kirby wrote in The Spectator, a man who never set foot in the newsroom killed off the title. And it won’t be the last casualty: the inquiries and court cases will last five years or more. Given that voicemail intercept was a standard tool for investigators working for many British newspapers (as Peter Oborne detailed in his definitive Spectator cover piece on the subject) there is every chance that the scandal could spread far wider.

This is the backdrop against which media regulation policy is being made. The Leveson inquiry is expected to be brutal for the newspaper industry. There is a feeling, across Fleet Street, that the industry is being made to suffer because David Cameron grew too close to Rebekah Brooks and that his means of atonement is to hold an inquiry into “the culture, the practices and the ethics” of the media. Some form of government regulation (and, ergo, the end of press freedom) looks grimly inevitable. We can laugh at Lewis, and his madcap ideas – but other, only slightly less sinister plans will not be far behind it.

Comments