In 1951, the American author Peter Matthiessen moved to Paris. The scion of a wealthy Wasp family, he had studied at Yale and served in the navy, narrowly missing the second world war. He was then recruited to the CIA by James Jesus Angleton and sent to Paris, where he kept tabs on left-wing French intellectuals and expat Americans. As he later explained in a letter to a friend:

When you’re 23, it seems pretty romantic to go to Paris with your beautiful young wife to serve as an intelligence agent and write the Great American Novel into the bargain. Weren’t you ever as young and dumb as that?

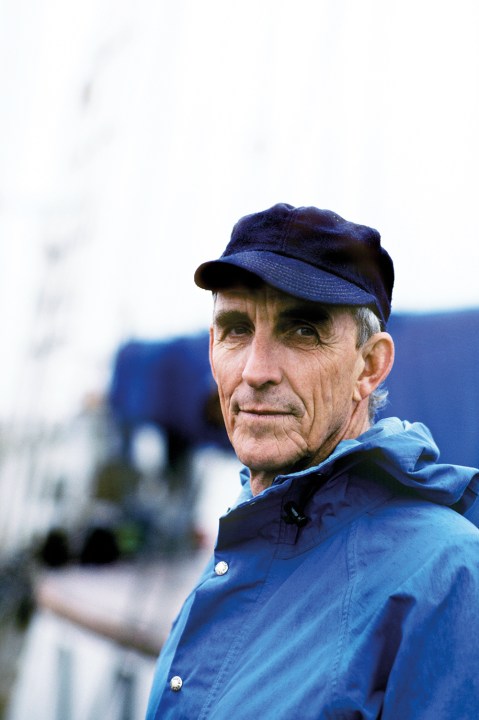

While in Paris, Matthiessen helped to found the Paris Review with funding from CIA sources. He later became a celebrated author of novels and nature writing, visiting many of the world’s last wildernesses for magazines such as the New Yorker. But he is best known for The Snow Leopard, a sublime travel book which combines a 250-mile walk on the Tibetan plateau with an exploration of Zen Buddhism. In Britain, his other books are little read. But, as Lance Richardson claims in this impressive new biography, there are ‘few figures in American letters who led such an eventful life during the past 100 years’.

Matthiessen’s love of nature began during childhood, but it was the need for money that led him to write about the natural world. This coincided with the early days of the environmental movement, as ancient American landscapes – everglade, prairie and desert – came under threat from industrial development and pesticide-heavy farming. Matthiessen was inspired by the explorer-naturalists of the 19th century, and over a long life his travels ranged from the Amazonian jungle to the African savannah, from the Siberian tundra to the indigenous tribes of Dutch New Guinea. But unlike the genteel nature writers of earlier generations he was animated by a sense of impending loss, describing himself as ‘an environmental writer and an environmental activist’.

He recognised that it was ‘uncommon… for a book to be artistically sound and also have an agenda’. But, argues Richardson, Matthiessen’s best nature writing becomes ‘a sublime conduit carrying the attentive, open-minded observer to glimpses of ultimate truth’. As a young man, he had dabbled in New Age religion; he later began taking LSD for therapeutic reasons; and after the death of his second wife, Deborah Love, he became a devoted follower of Zen Buddhism. This was the ‘journey of the heart’ that inspired The Snow Leopard, and the book’s originality comes from its blend of the scientific and the mystical, drawing on ‘ecology, divinity, ornithology and metaphysics, sometimes in the same paragraph’.

Matthiessen framed the book as a pilgrimage in memory of Deborah. But during the journey he was already writing letters to his future third wife, as well as various lovers. He had been unfaithful to Deborah throughout their relationship, despite ‘her beauty and elegance, her obvious goodness’. Even when she contracted terminal cancer he did not stop sleeping with the daughter of a family friend 20 years younger than himself (who later described him as ‘probably the unhappiest man I ever met’).

Infidelity was a feature of all Matthiessen’s marriages, often combined with compulsive travelling

As this biography reveals, infidelity was a feature of all Matthiessen’s marriages, often combined with compulsive travelling. Wives were left in a ramshackle farmhouse in the Hamptons to raise children and step-children – one of whom ended up with severe mental health problems, another of whom became an alcoholic, while a third criticised his father for his constant absences, only returning to ‘dole out emotional abuse within the family’.

Of course, Matthiessen’s chaotic personal life does not lessen the quality of his writing, but it does weaken his moral authority. His campaigns for the rights of Native Americans or the protection of rare habitats resemble telescopic philanthropy, while his commitment to Zen Buddhism – ultimately obtaining the rank of Roshi – becomes an escape from the obligations of fatherhood. Reading True Nature, it’s hard to retain much respect for the subject.

But this is no fault of the biography, which offers a rigorous and balanced account of this restless soul. Richardson gives sensitive explanations of how Matthiessen’s style developed to capture different landscapes, people and periods – from Caribbean fishermen to missionaries in South America. He also provides fascinating glimpses of the Matthiessen archive, from a mammoth unpublished manuscript on Bigfoot to an account of his intelligence career titled ‘The Paris Review vs. the CIA: My half-life as a Capitalist Running Dog’. Above all, Richardson shows how Matthiessen’s devotion to writing never wavered, despite depression, lawsuits and the painful gestation of several novels. In the process, he reveals the many sides (to quote Matthiessen’s own editor) of ‘an immensely complicated, neurotic, charming, iron-willed, uncertain, demanding author’.

Comments