When the University of Cambridge’s vice-chancellor Stephen Toope told the Times that students’ gap year projects abroad can build less resilience than the everyday lives of students from modest backgrounds, he was of course right. In today’s culture, the three months I spent attempting to teach English in southern Malawi in the late Noughties now feel like a dirty secret of over-privilege; something that’s deserving of the same discretion as having a childhood pony or the fact that you spent the Easter holidays in the Alps. Actor Matt Lacey’s three-minute You Tube sketch ‘Gap Yah’, that went viral in 2010, cemented the cliché: the pashmina-clad Orlando braying about chundering his way around ‘Tanzanah’, ‘Burmah’ and ‘Perah’ on a quest for “spiritual, cultural and political” enlightenment.

It swiftly became clear that my contribution in the classroom would have limits, even if my enthusiasm was plentiful

It’s a spoof certified by the Urban Dictionary’s definition of a Gap Year Tragedy (GYT): ‘the average student enlightened by the insight afforded by global travel to the extent of cringeworthy personality renovation.’

For my intake of (largely privately educated) 18-year-olds distributed amongst rural Malawian schools on the gap year programme I joined, the reality of trying to teach English to a mixed-aged class of 40-plus children was a challenge. But any real ‘resilience building’ seemed confined to the perils of using a long drop, surviving on a near-exclusive diet of greasy chapatis and navigating glitchy internet cafés as we bombarded Facebook with our ‘Where the Malawi are we’ adventure. Here was a well-trodden path of middle-class fun.

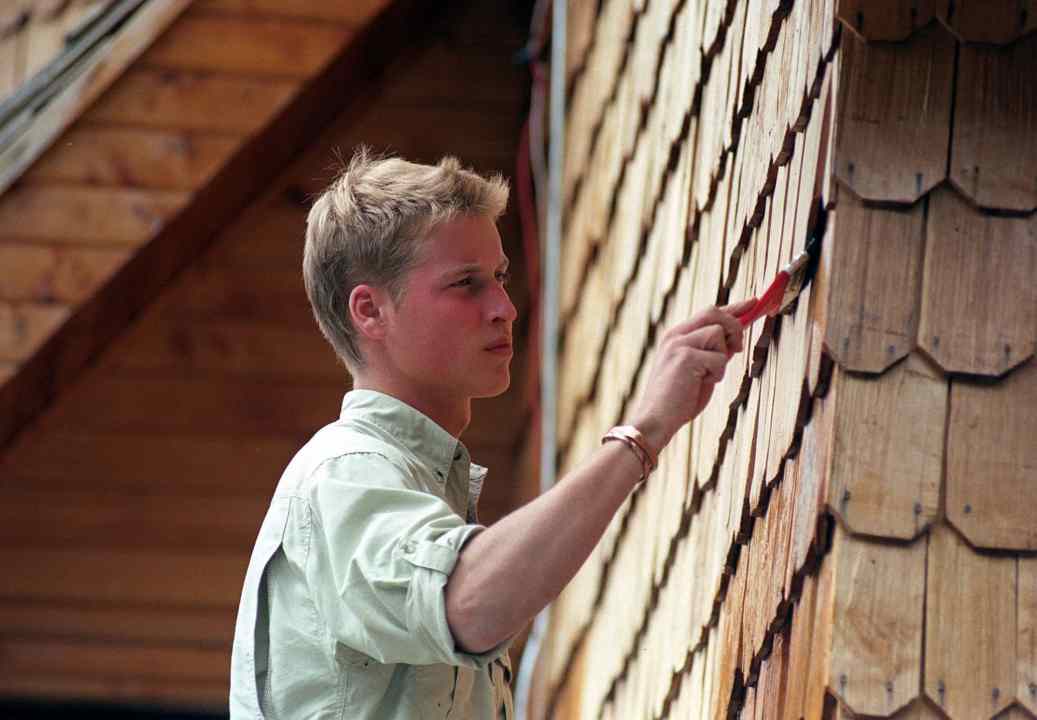

There is now the added uneasiness of ‘voluntourism’ to add to this once seemingly harmless caricature of gap years, the notion that short term stints of volunteering in developing countries do little to help – and can be detrimental – to the local community, even if they give the volunteer in question an inflated sense of purpose. Founder of ethicalvolunteering.org Kate Simpson said as the gap year industry was booming in 2006: ‘We wouldn’t dream of having unskilled teenagers working in a hospital or teaching a class in the UK.’ And even with the teacher shortage that Malawi faced when I visited (there was still a deficit of 83,000 primary school teachers in 2021), it swiftly became clear that my contribution in the classroom would have limits, even if my enthusiasm was plentiful. With little more than a week’s training, my offering was confined to something best equated to what the Australian ‘gappies’ who descend on British public schools can bring: a youthful injection of energy to an otherwise overworked staff room.

With the recent closure of Raleigh International (thrown into the spotlight with the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge as alumni), the future of volunteering charities might look a little more uncertain. But if my spoof-like experience in Malawi, laden with kikois, braided hair and beaded bangles makes me squirm, my decision to take a year out doesn’t. When I applied for my first job in journalism straight out of university, the Editor had little interest in my African escapades. Instead, she wanted to know how I had coped with tricky customers and handled the phone in the Wiltshire pub and clothing warehouse where I had earnt money ahead of going travelling.

And she had a point. It was here that the spike in my gap year ‘growing up’ chart happened: a teenager parachuted into unfamiliar and unwelcoming workforces where the only currency was hard work and common sense.

But the three months I spent backpacking around east Africa as the school year in Malawi came to a close, whilst not worthy of gracing a CV or mentioning in a job (or Cambridge) interview, were worth doing all the same. Indulgent they may have been, but here was the chance to truly break the cycle of exam mania, the pettiness of school and the confines of home life. It was perhaps something a little closer to the original gap year; the school leavers of the 1960s who embarked on the enviously care-free hippie trail through Asia. And for a generation of teenagers in the midst of a mental health crisis, struggling to cope with the all-consuming pressure to succeed, it’s not something that should be shunned by those who have the chance – whether it’s CV fodder or not.

Comments