‘Prizes are for little boys,’ said Charles Ives, the American composer, ‘and I’m a grown-up.’ It’s a pretty sound rule of thumb. The prizes worth having are usually those which reflect a body of work, not a single achievement. Cary Grant, the greatest leading man in the history of cinema, never won an Academy Award. Neither did Alfred Hitchcock, who made a few half-decent films. They received ‘lifetime awards’ from the red-faced academicians, but those gestures merely endorsed William Goldman’s view that, in Hollywood, nobody knows anything. As Billy Wilder told the producer who asked what he had been up to: ‘You first.’

Nobody takes much notice of the Grammys, which were designed to reward commercial success. The Tonys have become just another sleb-fest, like the Emmys. The winners rejoice, and the wise ones keep their own counsel. A friend, who picked up a gong for directing Paul Newman in the television adaptation of Richard Russo’s novel Empire Falls, said: ‘We are not deceived.’

In this country, where we are not supposed to boast, the Baftas have become a joke, and the Brits was always a noisy mess. The Turner Prize exists to flatter bad artists, and as for letting ‘the great British public’ vote for their favourite TV shows… well, look what you end up with.

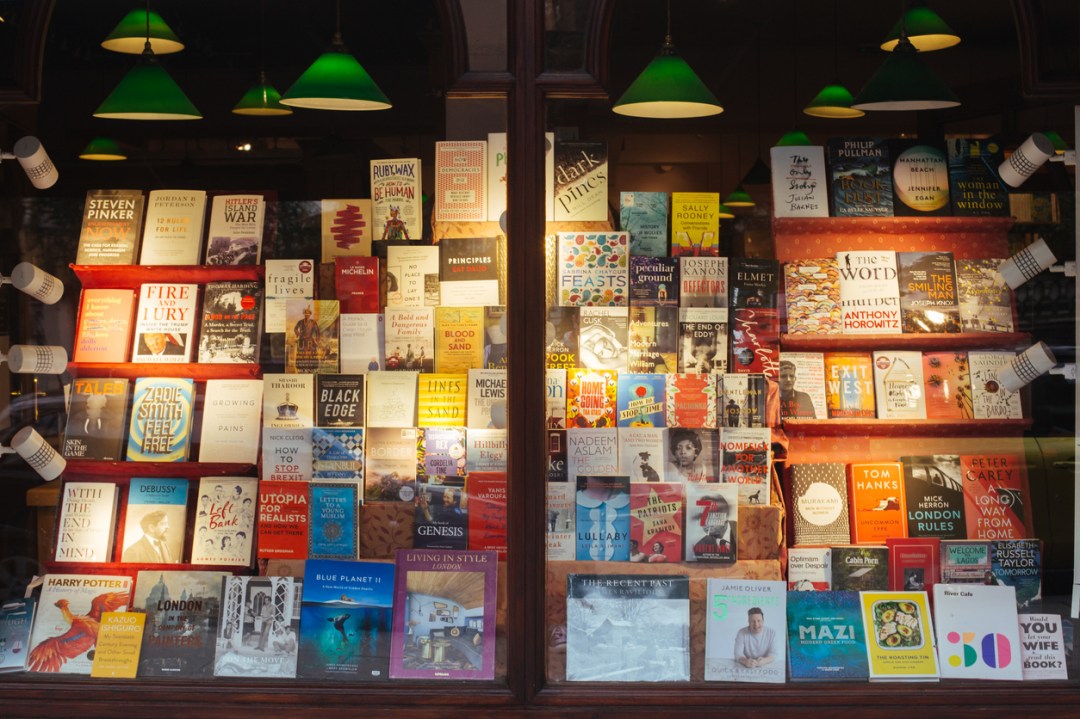

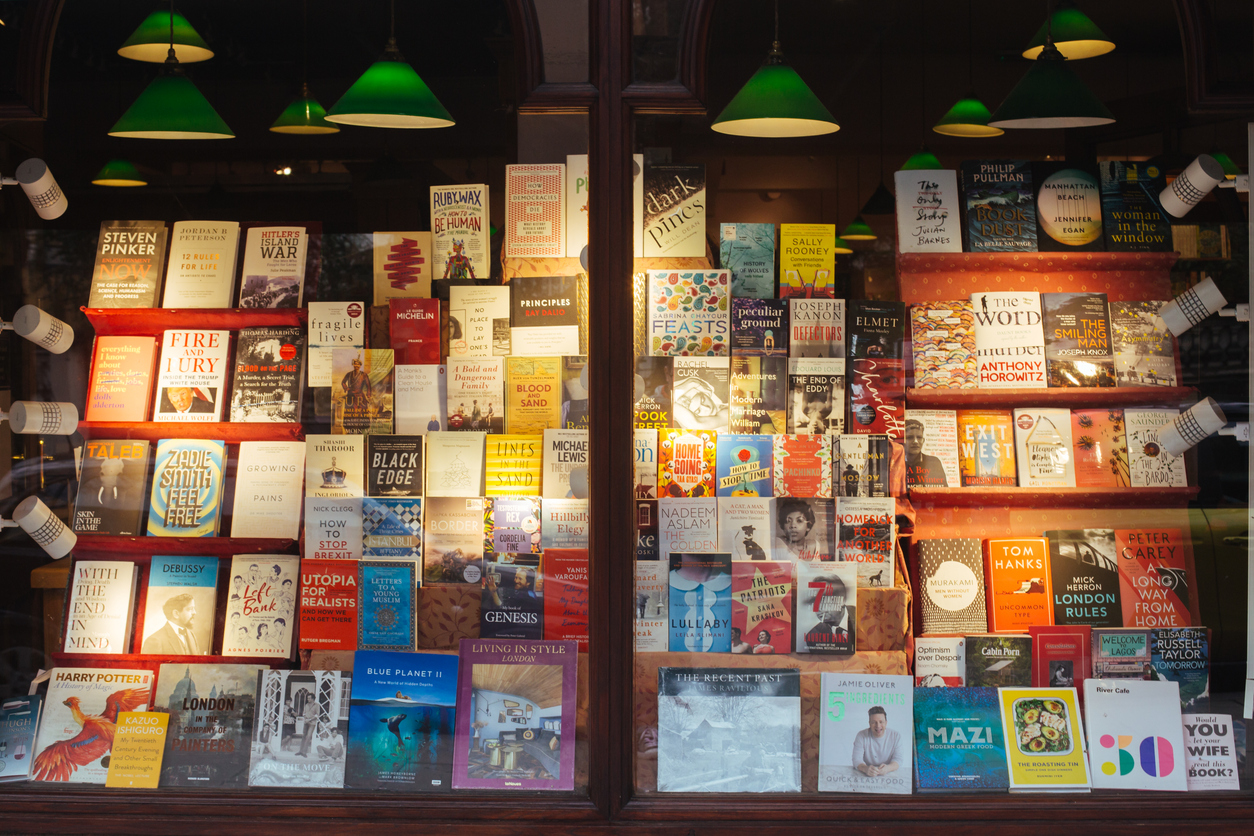

The Booker Prize, which is coming round again, was established in 1969 with the best of intentions. Not bringing books to the masses, whatever that snivelling phrase means, but encouraging people of all backgrounds to read novels. Now it means little. They do their best each autumn to bump it up, but it’s a tired pageant.

To be truthful it has never retained the significance it attained in 1980, when William Golding’s Rites of Passage pipped Earthly Powers, by Anthony Burgess. That was the year the Booker became a front-page story, not just a literary bunfight. Burgess glowered, but the judges got it right.

It’s a difficult balance to maintain, carrying ‘literature’ to readers beyond the parish of publishers and agents without stepping into the dung of showbiz. It doesn’t help when the prize’s spokespeople talk up the need for ‘accessibility’. If accessibility was truly the benchmark then George MacDonald Fraser would have romped home every time. His books were beautifully written, extremely funny, and sold by the lorry-load. Yet he was not their type. All those rude words about people who lived in other lands long ago! Smelling salts, Petunia.

So which type fascinates the Booker judges? Take a look at some of the winners – Ben Okri, D.B.C Pierre, Aravind Adiga, Eleanor Catton, Marlon James, Paul Beatty, Paul Lynch, Samantha Harvey. Since 2014, when the prize’s scope was broadened to accommodate American writers, ‘diversity’ has been shackled to ‘accessibility’. There were always women writers worthy of the prize, yet the judges overlooked Beryl Bainbridge and still overlook Rose Tremain. The most appalling oversight is Muriel Spark. Loitering with Intent (1981) was shortlisted; A Far Cry from Kensington (1988) was not. Naughty judges.

The Turner Prize exists to flatter bad artists, and as for letting ‘the great British public’ vote for their favourite TV shows… well, look what you end up with

Irish writers have been ever-present. Yet neither Brian Moore, nor William Trevor, nor John McGahern won the prize. Personal taste comes into it, of course, but those men wore the robes of greatness. They lived in a different realm to the Samantha Harveys of this world. When outstanding novelists have triumphed it wasn’t always for their best work. Graham Swift won for Last Orders, not Waterland; Ian McEwan for Amsterdam, not Atonement; Julian Barnes for The Sense of an Ending, not Arthur & George; Penelope Fitzgerald for Offshore, not The Blue Flower. Still, they were acknowledged, as was Kazuo Ishiguro, for The Remains of the Day. Another Irishman, Colm Tóibín, should have won in 2003 for The Master, when the prize went to Alan Hollinghurst for The Line of Beauty. A fine book, yes, but Tóibín’s portrait of Henry James was a masterpiece – and more readable than anything James wrote.

The judges are not always wrong. David Storey won in 1976 for Saville, mainly because Philip Larkin, who chaired the panel, drove it home like a chariot. In 2014 the winner was Richard Flanagan for The Narrow Road to the Deep North. And J.G. Farrell won twice, for The Siege of Krishnapur (1973) and for ‘the lost Booker’, Troubles, originally published in 1970.

The biggest howler? It must be V.S. Naipaul’s magnificent The Enigma of Arrival, published in 1986. Not even on the shortlist! Shades there of Hitchcock and Grant. Roddy Doyle, a former winner and chairman of this year’s panel, has said many of the books submitted were not worth reading. Let’s hope Andrew Miller wins for The Land in Winter, which is very wintry indeed. The man who wrote Pure and Now We Shall Be Entirely Free is worthy of the highest praise.

There is a literary award that has nothing to do with fashion. The David Cohen Prize, founded in 1993, has yielded a cast of outstanding recipients. The first four were V.S. Naipaul, Harold Pinter, Muriel Spark and William Trevor. Since then it has honoured Beryl Bainbridge, Julian Barnes, Tom Stoppard, Seamus Heaney and Colm Tóibín. Now there is a prize for grown-ups.

Comments