I wasn’t supposed to understand Potato language. It was my parents’ speech device employed when wishing to discuss certain apparently secret subjects in front of my brother and me. While chewing over some esoteric topic, they would suddenly lapse into Potato language, a.k.a ‘P-language’ or just ‘P’. Being a young child, the subject matter didn’t interest me – I was more intent on trying to figure out why on a whim they’d switch to speaking a discordant, discombobulated version of our every-day language.

Unbeknown to them, from the age of about seven I gradually became bilingual in P and by ten, I was fluent. As I grew older, I realised the point of converting to P was to discuss topics not intended for our ears.

As neither of our parents ever spoke to us in P, we didn’t speak it to them and as a teenager I discovered to my surprise that my brother had never picked it up. Being sensible and slightly older than me, he probably regarded it as a linguistic abomination.

P-language is constructed by inserting – unsurprisingly – the letter ‘p’ at strategic points in a word – generally before or after each syllable, depending on the word. The word ‘potato’ would be spoken as ‘puh-po-tuh-pay-tuh-po’. ‘Spectator’ would be ‘Spuh-pec-tuh-pay-tuh-por’. Gibberish perhaps, but occasionally useful gibberish.

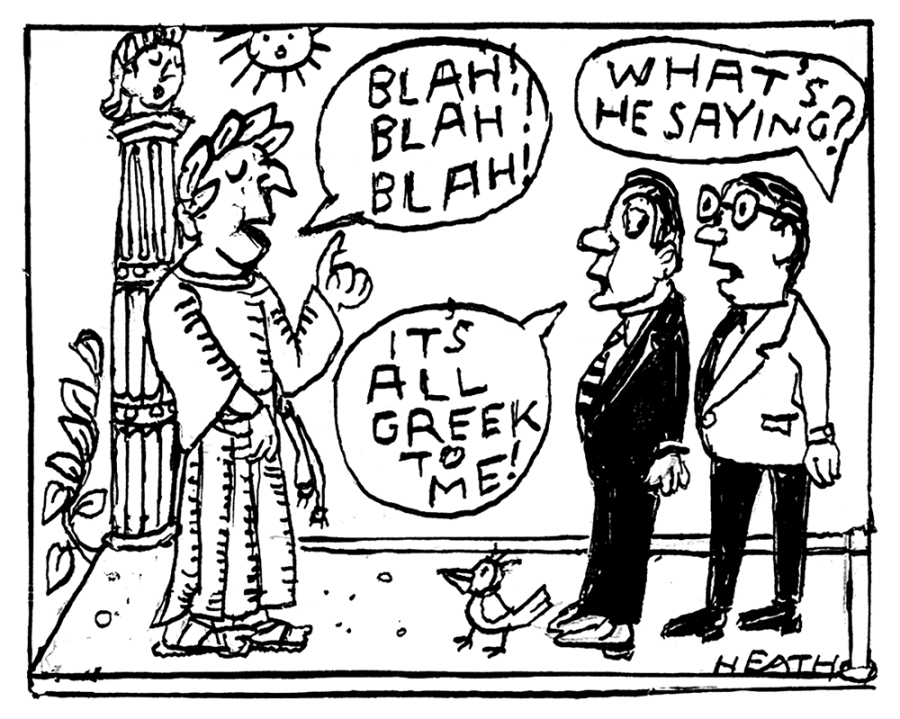

The word ‘gibberish’ is not, though, merely a description of nonsensical babble. It may refer to a linguistic game in which words are modified by the insertion of specific letters, as in P. Other examples are Pig Latin and Eggy Peggy.

For more serious and practical usage, a multitude of artificially constructed languages, or ‘conlangs’, have been created over many years. One of the most widely used is the international auxiliary language Esperanto – a universal language devised in the 19th century by Polish-Jewish ophthalmologist Ludwik Zamenhof. It’s intended to be simple to learn, with phonetic spelling and uncomplicated grammar. Among the other types of conlangs is International Sign Language, offering a means of communicating with those who are deaf. Polari was the language used within the gay community before homosexuality was decriminalised in 1967. Fictional conlangs abound within literature and film, such as Elvish in The Lord of the Rings and Klingon in Star Trek.

In my later teenage years, I confessed to my parents my long-standing fluency in their supposed secret lingo and P has since occasionally proved handy. A few weeks ago, my mother and I were in a café when we became aware of a couple at a table a little too close to ours sitting in silence occasionally glancing at us as we quietly mulled over an old family matter. Realising the eavesdropping, we spoke in P only to remark on the fact of the attention before returning to chatting again in plain English about a banal subject.

This incident was a rarity but I am keen to preserve the language within my family. My two great-nieces are aged two and three and their highly receptive brains would probably cotton on to it easily. I’m not sure what their parents would make of their great-aunt chattering in gobbledygook, so I’ll wait a few years. Their parents might adopt the ‘if you can’t beat them join them’ approach – or simply warn the children of an impending visit by the eccentric great-aunt, with her tongue-twisting parlance.

Comments