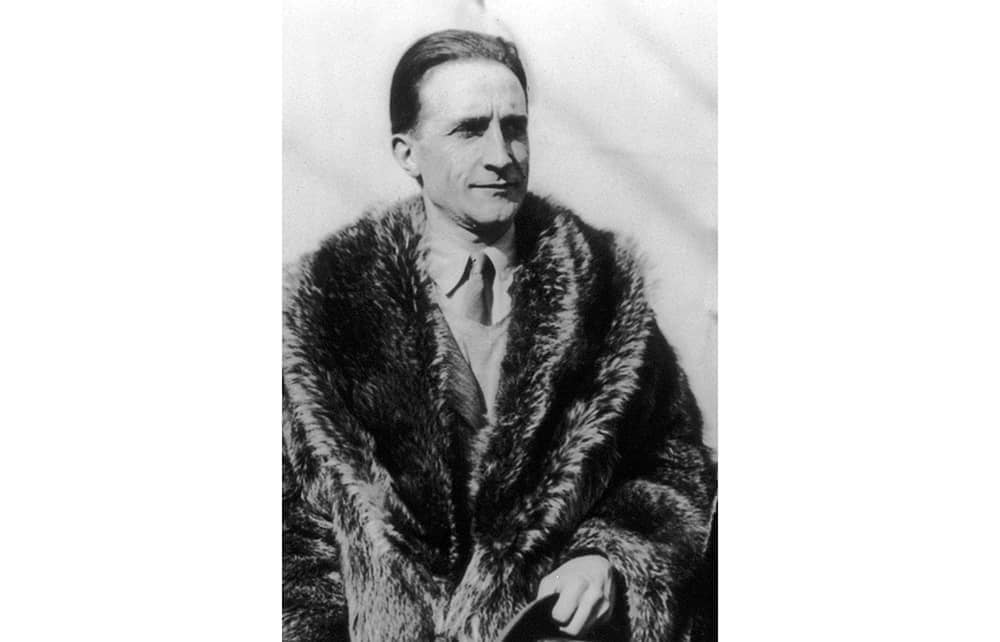

One could compile a fat anthology of tributes to Marcel Duchamp’s charm – especially what one friend called the artist’s ‘physical fineness’ – but it would be hard to top Georgia O’Keeffe’s memory of their first meeting:

Duchamp was there and there was conversation. I was drinking tea. When I finished he rose from his chair, took my teacup and put it down at the side with a grace that I had never seen in anyone before and have seldom seen since.

A tempest stirred by a teacup!

Duchamp exerted – without ever exerting himself – a magnetism at once obvious and inexplicable

Made famous by his painting ‘Nude Descending a Staircase’ (1912) – ‘an explosion in a shingle factory’ per the New York Times – Duchamp was effortlessly attractive to both men and women. A mysterious figure, kind, clever, calm, elegant, easy and almost programmatically unconventional, he exerted – without ever exerting himself – a magnetism at once obvious and inexplicable. Surrounded by lovers, friends and admirers, he remained noticeably detached; the same woman who remarked on his physical fineness also called him a ‘poor little floating atom’.

The collision of that atom with two others in the febrile New York art world c.1917 forms the superheated core of Ruth Brandon’s Spellbound by Marcel: Duchamp, Love and Art. Breezily entertaining (there’s more love here than art), its essential shape is triangular, with Duchamp inevitably at the apex. Henri-Pierre Roché, an unrelentingly priapic French journalist, and Beatrice Wood, an aspiring actress and incurable romantic, were both in love with Duchamp and then with each other but still also with Duchamp. Although Roché and Wood each later achieved a degree of fame (he wrote the novel Jules et Jim; she became a celebrated ceramicist), it’s the involvement of Duchamp that makes this particular love triangle noteworthy.

Wood met Duchamp at the hospital bedside of the composer Edgar Varèse, who later married Duchamp’s occasional lover Louise Norton, who was at the time still technically the wife of the poet Allen Norton. (You see how it goes.) Wood was instantly smitten: ‘Marcel smiled. I smiled. Varèse faded away.’ As she remembered it: ‘At that moment we were lovers.’ Except that they didn’t have sex. Wood was still a virgin, and for Duchamp that marked her as off limits. (There were, after all, vestiges of convention in his makeup.) In order to deflect her amorous passion, he introduced her to Roché, who had zero scruples about virginity – in fact, zero scruples tout court.

Duchamp, Wood and Roché were together responsible for The Blind Man, a little magazine published to celebrate the 1917 exhibition in New York organised by the Society of Independent Artists, a show chiefly remembered today for the scandal of Duchamp’s rejected ‘Fountain’ (1917), a urinal signed R. MUTT that outraged almost everyone. The second issue of The Blind Man carried Alfred Stieglitz’s evocative photo of the offending item and an editorial on ‘The Richard Mutt Case’, defending the artist while maintaining Duchamp’s anonymity. The brouhaha is typical of him: at the centre of it yet absent. It’s a pleasing coincidence that ‘Fountain’, as photographed by Stieglitz (O’Keefe’s future husband) is itself essentially triangular. The original plumbing fixture vanished; the scandal over his ‘readymades’ still simmers, immortalising Duchamp.

There’s a fabulous cast of supporting actors on this busy stage: the collectors Walter and Lou Arensberg (she had a torrid affair with Roché, thereby shattering the original love triangle), Isadora Duncan (who commissioned Wood to make her some long, floating scarves of the kind that eventually killed her), Francis and Gaby Picabia (both loved by Duchamp), William Carlos Williams, Man Ray and Mina Loy. Brandon is a congenial stage manager, adept at presenting and dismissing her dramatis personae. Unblushing, she dispenses salacious gossip, patiently decoding the diaries of Roché, who kept a record of his myriad conquests, noting the variety of sex acts performed (he was apparently orally adept). Did you want to know how Duchamp felt about pubic hair? I guess the wordplay of his female alter ego Rose Sélavy should have tipped us off: abominables fourrures abdominales (abominable abdominal fur).

There’s also a dramatic backdrop: across the ocean from all the New York coupling and uncoupling was the carnage of the war in France that Duchamp, exempt from military service due to a slight rheumatic heart murmur, had come to New York to escape. Here was a fundamental disconnect: while his generation of Frenchmen was decimated, he dreamed up conceptual art and – better, to his mind – played chess.

The weakness of Brandon’s book is that Wood and Roché aren’t as interesting as Duchamp (who is?), and if you want to know about Duchamp (who doesn’t?), the book to read is Calvin Tomkins’s graceful, intelligent, and thoroughly researched biography, first published in 1996 and still the gold standard. It, too, is full of salacious gossip, with acute commentary on the art as a bonus.

Comments