I do not yet have any children of my own, but a large extended family means plenty of young nieces and nephews to buy presents for come birthdays and Christmas. Those moments provide an opportunity to indulge in some pedagogic guidance: I’ll be damned if you’re getting the latest Fifa game for the PlayStation 5 – you can have a real football to kick around outside. Ditto the inevitable requests for Nintendo virtual reality headsets and Frozen merchandise. Happily, I’ve got at least one Christmas present this year sorted already – and I’m quietly confident my nephew is going to enjoy reading it as much as I just have.

Lord Robert Baden-Powell’s life-guide book Rovering to Success is a century old this year. It came 14 years after his flagship publication Scouting for Boys and it is, to my mind, as good a read and as relevant today as it was in 1922. Maybe even more relevant. For of course today’s young boys have new obstacles (or ‘rocks’, in Rovering’s diction) to navigate that Baden-Powell could scarcely have imagined: the lure of the video game and the smartphone on the one hand, and an assault on supposed ‘toxic masculinity’ on the other. Rovering to Success provides some stabilising moorings for youngsters amid the choppy seas.

In the 250-odd pages, Baden-Powell sets out his guidance via a nautical analogy: ‘Paddle your own canoe,’ he implores his young readers. ‘Don’t rely upon other people to row your boat. You are starting out on an adventurous voyage… You will meet with difficulties and dangers, shoals and storms on the way. But without adventure life would be deadly dull. With careful piloting, above-board sailing, and cheery persistence, there is no reason why your voyage should not be a complete success, no matter how small the stream in which you make your start.’ Thus he sets out his advocacy of self-reliance and rugged individualism.

Each chapter is devoted to a ‘rock’ that might be strewn in one’s way, from horses, wine and women (in the terms of the old toast) to ‘cuckoos’ and ‘irreligion’. Sure, some bits now read as sentimental or outdated (unless your young lad has a predilection for gambling on horses). You won’t agree with every word. Baden-Powell’s sometimes strict puritanical views – he viewed masturbation as morally ruinous – may cause you to skip past those sections containing his ruminations on sex.

‘Don’t be tempted like so many to rush to extreme views before you have seen something of the world,’ he writes. The Twitterati would do well to take note

But even among the apparently dated words there is valuable modern-day guidance. The chapter on horses is devoted not just to cautioning against gambling, but covers everything from playing honest sport to learning to practise thrift (‘Indeed it is a bit of adventure that appeals to a sporting mind. Poor millionaires!’). Throughout he passionately urges his readers to refrain from victimhood and self-pity: ‘Salt is bitter if taken by itself; but when tasted as part of the dish, it savours the meat. Difficulties are the salt of life.’

He lists those things that will act as antidotes to the rocks in one’s way: ‘Active hobbies and earning money; Self-control and character; Chivalry and health of mind and body; Service for your fellow-men and for God.’ I challenge anyone to list more concisely the ingredients of a happy life.

He argues, as you would expect, in favour of embracing the great outdoors. One of his hobbies – like in the old Hunting with Mr Jorrocks book – is cutting sticks in the hedgerows and woods to make them into walking sticks. Even the simplest outdoor activity can be of limitless pleasure: ‘It doesn’t sound a very exciting [hobby], yet… it it is sufficiently attractive to lead you mile after mile in the hunt for a good stick which would otherwise be untold weariness; and the satisfaction of securing, of straightening and curing a good stick is very great.’

Each chapter concludes with ‘Helpful books’ for further reading. The author’s faith in the intellectualism of his young readership can’t help but raise a smile: the young rovers are urged to take up everything from Lord Avebury’s The Pleasures of Life to L.P. Jacks’s The Art of Living Together. Each chapter also contains a short selection of quotes comprising ‘What others have said on the subject’. For example: ‘Lots of fellows demand their rights before they have ever earned them’; and ‘Young man! Nature gave us one tongue, but two ears, so that we may hear just twice as much as we speak.’

A couple of aspects are particularly noteworthy. First, there is an articulate defence of the virtue of the stiff upper lip. Stoicism is one of our great national strengths and Baden-Powell celebrates it. But his advice is not as emotionally repressed as you may expect. In the section titled ‘Self-expression’ he writes: ‘If a fellow feels moved to express his thoughts and ideas, whether in poetry or writing, or speaking, or in painting or sculpture, most certainly let him do it. I would only suggest don’t be tempted like so many to rush to extreme views before you have seen something of the world.’ The Twitterati would do well to take note.

And, while the usual suspects will be quick to denounce the book for presumed glorification of our imperial past, it is Baden-Powell’s consistent emphasis on the virtue of seeing both sides of an argument that struck me. On complex issues such as imperialism he says we should consult all the various perspectives and arguments before leaping to make judgment. Thus at one point he divides the page into two and gives the ethical arguments for and against the Empire in turn. Who could quarrel with this insistence on hearing both sides of an argument and then, as he puts it, ‘worry them out for yourself and see which is really going to benefit the majority of the nation in the long run, and make up your own mind accordingly’?

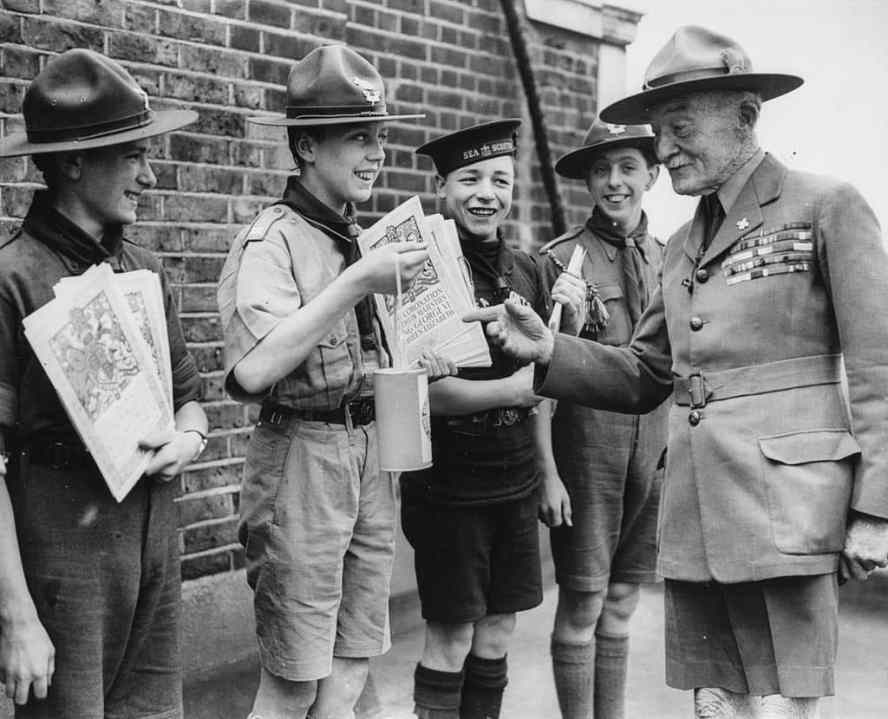

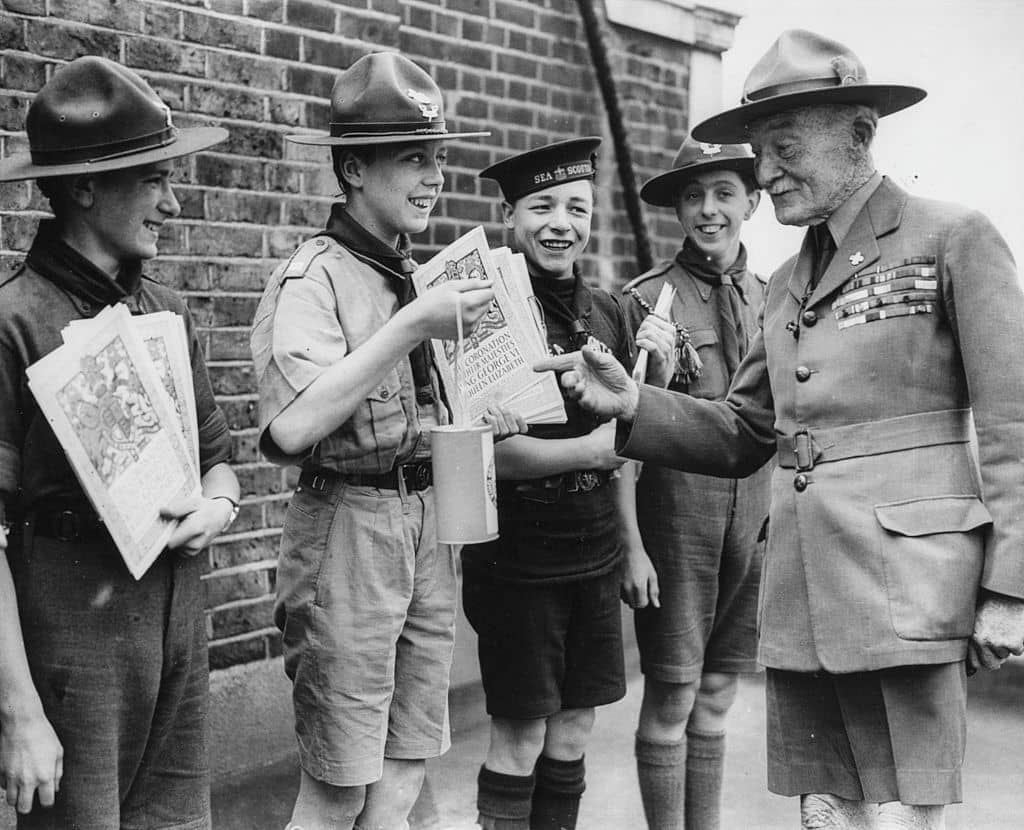

Baden-Powell is of course not free of controversy. In June 2020, his statue in Poole overlooking Brownsea Island – the site of his first Scout camp – had to be temporarily boarded up for protection after it appeared on a target list during the George Floyd protests. He has variously been accused of racism, homophobia and support for Hitler – a portrayal rejected by his biographer. But Baden-Powell’s role in enriching the childhoods of so many – my father, brother and myself included – through the Scout movement he created is a legacy that can never be taken from him. And the sincerity of his desire to set youngsters – both boys and girls – on the right path shines through in his writing.

Instructional books for children and adolescents are two a penny. But only a few do really well. The reassurance in The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse by Charlie Mackesy (formerly of this parish, as a Spectator cartoonist) struck a chord for many during the uncertain times of the past three years and has become the UK’s bestselling hardback book since records began. The Dangerous Book for Boys by Conn and Hal Iggulden has, pleasingly, revived the spirit of the Just William books (the first of which was, coincidentally, also published a century ago this year) and been a runaway bestseller. (There is of course also the contribution of Meghan Markle, published last year, on which we shan’t dwell.)

So Baden-Powell is not without competition. But, like Rudyard Kipling’s poem ‘If’ (often voted the nation’s favourite), there is a core philosophy in Rovering to Success that I think – and hope – parents will want to pass on to their young children. Even its most homespun advice feels sounder than ever set among the madness of the modern world.

So seek out a copy (it is even freely available online), and pass it to a loved one with Baden-Powell’s gentle urge for a life of vigorous activism: ‘For me it is nine o’clock in the evening of life. It will soon be bedtime. For you it is 11 o’clock in the morning – noon-tide; the best part of the day is still before you… you will sleep all the better when bedtime comes if you have been busy through the day.’ He ends: ‘With all my heart I wish you success, and the Scout’s wish – Good Camping.’

Comments