British foreign policy has always oscillated between isolation and engagement. The division has shaped Conservative thinking over generations. The archetypal icon of engagement is Winston Churchill. In the wake of the Munich Agreement, Churchill made his greatest anti-appeasement appeal: ‘What I find unendurable is the sense of our country falling into the power, into the orbit and influence of Nazi Germany.’ He was for rearmament and, ultimately, for war.

Churchill had in his sights the isolationists of the right – those Tories who would not ‘die for Danzig’. Victory in the second world war, the western alliance, Nato, America’s nuclear guarantee, the European Union, communist collapse – all seemed to prove Churchill triumphant and correct.

Churchill’s legacy may yet emerge intact after the negotiations to end Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine. Donald Trump’s love-in with Russia’s bloody autocrat may not last. Or it may never have been meant in the first place. Or, while meant, it may in the end matter less to the President than his ego – and the shimmering prospect of a Nobel Peace Prize.

This way of thinking foresees Putin banking his gains. Ukraine would be divided, with European ground troops in the western part of it, backed by American air power and a security guarantee, while Trump bags the minerals.

A just peace? Certainly not. But peace nonetheless. Life appears to return to normal. The media’s febrile bandwagon moves on. Keir Starmer breathes a sign of relief, whatever happens during his Washington meeting with Trump.

However, even if the western alliance endures, it has in the last week been hit by a ‘trustquake’ – according to Edward Lucas, the foreign affairs and security specialist. For once, a journalistic neologism is, if anything, an understatement, though it could be said that Trump is simply screaming in our ear a message that other presidents have chosen to whisper.

A world in which the United States votes with Russia at the United Nations – while even China abstains – is not one in which Europe can rely on America. And if Europe can’t rely on America, how can it rely on Nato and America’s conventional power, let alone its nuclear deterrent? No wonder Friedrich Merz, Germany’s incoming Chancellor, now speaks of European independence from America.

The apple cart has been turned over and there’s no way of knowing which way the apples will go a-rolling

Here in Britain, such concerns have resurrected the debate between Churchill and the isolationists, between engagement and a more insular approach. Modern spokesmen for each are emerging.

On the engagement side, there is Mike Martin, the Liberal Democrat MP for Tunbridge Wells. Like Churchill, Martin has fought for his country abroad in the army. And like him again, he backs engagement. He sees Russia as the main threat to our security and wants a new European Treaty Organisation to replace Nato, complete with British boots on the ground in Ukraine and integrated European supply chains.

On the isolation side, there is Nick Timothy, the Conservative MP for West Suffolk. Timothy is a highly original One Nation Conservative with trenchant views on migration control and industrial strategy. He doubts that the will for collective European action exists. Britain, he argues, ‘may be on its own’. He therefore favours as much self-sufficiency in procurement as possible.

It is questionable whether, when push comes to shove, Martin really speaks for the party that came out against the Iraq war. Similarly, it is doubtful whether Timothy’s view will prevail in a party that has been wedded to internationalism in security policy for more than three quarters of a century. (Though Kemi Badenoch’s defence speech to the Policy Exchange thinktank this week showed signs of change on that front. ‘Our foreign policy should seek to support our national interest,’ she said.)

The point is that the apple cart has been turned over and there is no way of knowing, as D.H. Lawrence put it, which way the apples will go a-rolling.

Will Labour, in the tradition of Ernest Bevin, hold fast for deterrence and higher security spending? Or will it, following George Lansbury, turn instead to its pacifist tradition, and balk at the cuts to other services which more defence spending would require? Starmer’s announcement this week that defence spending would rise from 2.3 per cent to 2.5 per cent, paid for by cuts to the aid budget, would suggest the former, although the increase is smaller than the government says it is.

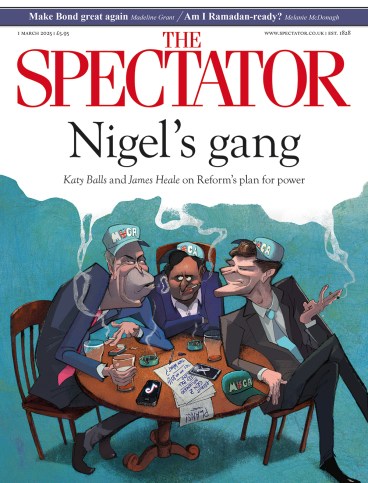

Then there is Reform. Whatever one makes of Nigel Farage’s views on Putin, the new party, with its Britain-First reflexes, J.D. Vance-like preoccupation with culture, Trumpist braggadocio and MAGA mentality looks like a natural repository for isolation. It would not surprise many to hear the party declare that Ukraine isn’t worth the bones of a single British grenadier.

Martin, of course, would still argue that home defence is essential; Timothy that international relations are unavoidable. In this sense, engagement and isolation are shorthands. But they stand for elemental impulses in the British psyche.

Neither view may have the luxury of time. Creating Europe-only supply chains would take many years. So would self-reliance, insofar as it’s possible. Estonia’s HIMARS multiple-launch rocket systems, Lithuania’s black hawk helicopters and our very own Trident deterrent all depend on American repair and refurbishment.

One take is that Russia is so exhausted by war as to have little capacity for more. Another is that it will be ready to strike again long before Europe is in any shape to resist. Would the British people be willing to extend our nuclear protection to Germany? Are they really, truly up for reimagining our public spending settlement – or, if necessary, for conventional war in eastern Europe? We see through a glass darkly.

Comments