Early on in this fascinating history Stephen Alford makes an important point: because Elizabeth I and the settlement between monarchy, church and state survived, because the threat of foreign invasion was thwarted or failed to materialise, and because the sense of national identity fostered by the Tudors proved robust, we see that first Elizabethan age as a confident and assured success story. But to those involved it was far more precarious, with victory anything but assured and survival a daily challenge.

Alford dramatises this by imagining Elizabeth’s assassination in St James’s Park, followed by invasion by the superpower, Spain. Aided by popular uprisings, the live burnings of Elizabeth’s ministers and clergy — who history would have portrayed as an aberrant heretical clique — and the suppression of English translations of the Bible, England would have returned to the Catholic fold as Hapsburg England under the hero of Christendom, King Philip of Spain. For much of Elizabeth’s reign this was a plausible scenario.

Alford’s subject is the intelligence organisation at the heart of the militarily weak Elizabethan state, and the question as to whether the ‘more obsessively a state watches, the greater the dangers it perceives’. The organisation was run mainly by the Queen’s secretary, Thomas Walsingham, ‘the cool, organising intelligence at the centre of things’. After his death in 1590 it was overseen by the two Cecils, William and Robert, the father and son team who effectively ran the country.

Walsingham was an austere, devoutly religious man who amassed no fortune and who was deeply influenced by witnessing the 1572 St Bartholomew’s Day massacres in Paris when up to 6,000 Protestants were butchered. That was what he, the Cecils and their queen were convinced would happen if Elizabeth were deposed. ‘There is less danger,’ he concluded, ‘in fearing too much than too little.’

He was ably assisted by Thomas Phelippes, a cryptographer of genius who was also a successful recruiter and runner of agents (a rare combination). Mary, Queen of Scots, who probably thought he worked for her, described him as ‘of low stature, slender every way, dark yellow-haired on the head, and clear yellow-bearded… eaten in the face with small pocks’. Like his master and others on the Privy Council, Phelippes’s religious faith was inextricably entwined with the security of the state, a phrase first used at this time. This nexus of beliefs, reinforced by the threat of invasion and the horrifying prospect of religious civil war, became, in Alford’s words, ‘the politics of raw survival’, a struggle in which all means were justified.

What exactly was the threat? There were three attempted Spanish invasions — the landing of 500 Spanish troops in Ireland in 1580 and the armadas of 1588 and 1596 — and a number of plots to assassinate Elizabeth, justified in advance by successive popes. None of these plots amounted to much, although the aspiration was real enough, despite one plotter’s disarming description of his own plans as ‘the dangerous fruits of a discontented mind’. Fuelling it all was the passionate desire of the English Catholic resistance, with the backing of the major continental powers, to replace Elizabeth with Mary, Queen of Scots or, after Mary’s execution in 1587, with Philip of Spain.

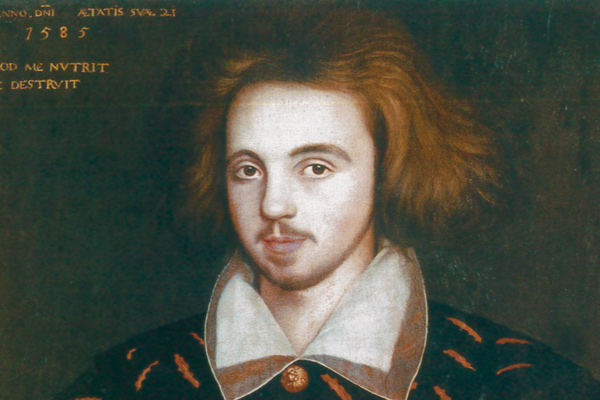

Figures are inevitably imprecise, but Alford estimates that Walsingham had some 40 to 50 reporting agents at home and overseas, ranging from such figures as Anthony Munday — a collaborator of Shakespeare’s — to the comically conceited William Parry — ‘born for self-destruction’ — to the sinister and effective Robert Poley, who was with Christopher Marlowe when he was killed. (For me, the only disappointment in this book is Alford’s dismissal of the evidence for Marlowe’s association with Walsingham as ‘sketchy and circumstantial’ without apparently taking into account the Privy Council resolution of 29 June 1587 urging Marlowe’s college not to withhold his degree since during his absences he had ‘done Her Majesty good service, employed as he had been in matters touching the benefit of his country.’).

According to one estimate, the enemy Walsingham’s network penetrated so successfully comprised around 300 English émigrés on the continent, including influential figures from the nobility and gentry. Over 40 years around 471 priests secretly worked to save English souls or spread sedition — depending on your point of view — of whom 294 were imprisoned, 116 executed and 91 banished. Men such as William Allen, their principal organiser, and Edmund Campion, their most inspirational martyr, sincerely believed they were doing God’s will in fighting for the soul of England.

It was Allen’s account of Campion’s brutal death that turned Campion into a martyr, a curious part of which was Allen’s sale — within months of the event — of alleged bits of Campion’s rib as holy relics. As Alford shows, it was impossible for this struggle to be only religious: martyrs were simultaneously counter-revolutionaries backed by hostile foreign powers. The protracted cruelty of hanging, drawing and quartering and the use of the rack (conventional for the period, upon authorisation by the Privy Council, which memorably thanked the torturers for their ‘pains’) undoubtedly helped the state to win the security war, while arguably losing the propaganda war.

Was it justified? Alford concludes that the government ‘was absolutely right to believe the truths of plots and conspiracies and plans for invasion and assassinations’. However, they ‘overestimated their enemies’ intelligence, cunning and organisation’. What gave the struggle its venom was the context, the religious wars that ravaged 16th-century Europe. If you want to know the inside story of that struggle, the dark heart of calculation and the fight for survival, then this is the book to read. I know no better.

Comments