Last autumn the principal of the John Wallis Church of England Academy, where I work as the head of external relations, summoned me to his office and presented me with a Yondr phone pouch – ‘You know, like the ones you get at concerts?’ I blinked at him, hoping this would disguise how uncool I am.

He handed me a pocket-sized fabric pouch with a magnetic latch that was opened using a special unlocking base. He had ordered one for every pupil in the school. His idea was that they would all put their phone inside their pouch first thing in the morning and it would not be released until the end of the school day. If students could still carry their phones around, it gave them more of a feeling of ownership than a policy which took all the phones away. Still, the scheme didn’t sound particularly groundbreaking to me.

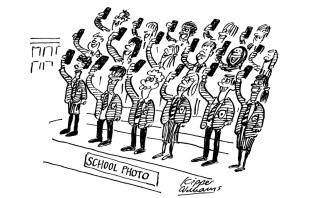

Separating a teenager from their phone is worse than taking a dummy from a baby

How wrong I was. Fast-forward to the spring term and we’ve seen a 42 per cent decrease in low-level disruption sanctions, a 40 per cent decrease in after-school detentions and a 25 per cent decrease in truancy. These statistics don’t begin to do justice to the cultural change that the school has seen in such a short space of time. The pupils are better behaved and less distracted. They are noisier, yet more respectful.

One day in January, I was sitting working when there was suddenly a wave of commotion coming from the playground during break time. Using an inbuilt reflex all teachers seem to possess, the principal was in his coat and outside before I’d even noticed what was going on. From the window I saw a flurry of snow had begun to fall and outside students were running around, laughing and shouting. Why was this different? Because not one of them was experiencing it through a screen. They were enjoying themselves and making memories instead of capturing them.

Break times are no longer sullen opportunities for students to sneak a glimpse at Snapchat. All the social skills that had diminished during the pandemic are being re–learnt, and the school has come alive with the noise of hundreds of pupils fully engaging with each other. Boys awkwardly approach girls at lunch rather than ‘sliding into their DMs’, and students are animated and energetic instead of sitting in silent huddles with their heads bowed, staring at a screen hidden from teachers in their inside blazer pocket.

Oppressive social-media notifications have stopped chipping into the day. The students themselves admit being more focused in lessons and more aware of the environment around them. I’ve noticed small changes such as pupils making more effort to hold doors open for staff and being more co-operative when challenged. Some teachers have reported a need to alter their lesson style because students are so much more attentive.

One unforeseen consequence was that students became anxious about knowing the time, particularly in lessons. Extra clocks were ordered to supplement those already around the school, but what we did not anticipate was just how few pupils were able to tell the time using an analogue clock. Digital interfaces have surrounded them ever since they understood the concept of time and without practising something you’re taught at a young age, or not as the case may be, this knowledge quickly evaporates.

When the new policy was first implemented, staff watched pupils go through the different stages of grief at the loss of their phones: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Separating a teenager from their phone is worse than taking a dummy from a baby, which is perhaps why so few schools are brave enough to have done it.

Breaking the addiction cycle has had an effect at home too. Parents have reported that their children are engaging more around the dinner table and depending less on their phones as they grow used to a world that doesn’t revolve around them. Other parents have asked about borrowing Yondr pouches for domestic use.

But what about parents who say: ‘I need to contact my child’? Tough. Until mobile phones, external communications during the school day were adult-to-adult. A parent would ring the school with news of a family emergency, a change in travel plans, a forgotten lunchbox, and this would always be dealt with by a member of staff. Depending on the urgency of the situation, the teacher would manage when and how a message was conveyed, from calling a student out of a lesson to visit the headteacher’s office, to a quiet word with a form tutor at break time. The aim was to cause as little disruption to the child’s day as possible. Contrast this with one parent who felt it was acceptable to text their child during a lesson to tell them their aunt had died, leaving them distraught for the rest of the day, without their family around them to provide comfort.

While students at the John Wallis Academy do not have the freedom to access their phones during the school day, what they do have is the freedom to be a child. Without the distractions of social media, parental presence and the auto-response of encountering each moment through the camera, they are given a chance to experience the childhood we didn’t realise we were so lucky to have.

Comments