Andrew Lambirth talks to the artist Keith Coventry about drawing inspiration from Sickert, Churchill and Ladybird Books

Keith Coventry has no time to visit the two lap-dancing clubs that lurk a few doors down from his studio, a small room with barred windows in a light-industrial block in the East End. Here, he puts in long hours, often forgetting to eat in his total immersion in the act of putting paint on canvas. He grudgingly admits to being a workaholic.

This is where he painted ‘Spectrum Jesus’, which two months ago won him the £25,000 John Moores Painting Prize, one of the most prestigious accolades in the art world. Winning the John Moores does not guarantee immortality — not much does, except perhaps genius — but it can make a difference. Coventry joins some of the big names of modern British art of the past half-century: Roger Hilton, David Hockney, Euan Uglow, John Hoyland, Peter Doig are all former winners, as well as a number of artists unjustly neglected today, such as Henry Mundy, Myles Murphy and Mick Moon. The prize is awarded every two years at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool to the best work from an open submission, and is judged by a panel of experts. This year Gary Hume, Alison Watt and Sir Norman Rosenthal were among the judges.

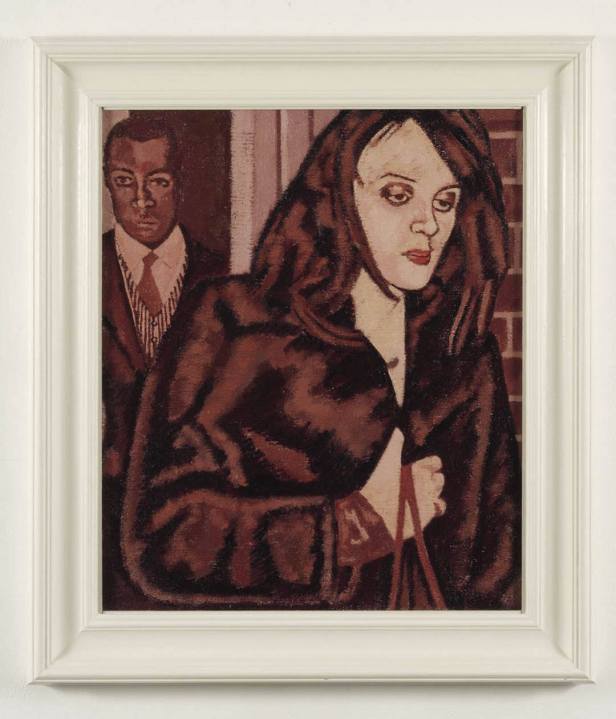

Coventry (born 1958) is pleased to have won the John Moores. It is perhaps a measure of the enviable international reputation he has established over the past decade or so, and a recognition of his remarkable versatility. For Coventry paints in a number of very distinct styles, and seems to embody the stylistic plurality so typical of our age. He makes what look like minimalist abstracts inspired by the layout of housing estates; he paints white-on-white abstracts which are actually scenes of typical Englishness, such as the royal family at public functions; he makes sculptures of snapped-off saplings or destroyed park benches from inner-city no-go areas; he paints black-on-black abstracts based on flower-arranging or bright Mediterranean scenes by Dufy; and he reinterprets Sickert in a series of figurative paintings called ‘Echoes of Albany’. Coventry’s variousness, which disconcerts some critics, is deeply appealing.

His winning ‘Spectrum Jesus’ (2009) is one of a series of canvases inspired by a book he found in the London Library on the notorious forger Van Meegeren. Coventry often goes to the London Library to research. ‘I like research, but for a lot of people it’s an excuse for doing nothing. I go there, spin myself around and then just pull books out, engage with them and sometimes something clicks.’ This is where chance comes into his work, the necessary leaven for an artist who likes to have everything decided before he picks up a brush. The discovery of Van Meegeren’s paintings was a chance event, though Coventry also recalls a Ladybird book he had as a child about Vermeer, Rembrandt and Rubens, which pictured the forger.

‘Spectrum Jesus’ is a very blue and atrabilious painting — Coventry repainting Van Meegeren in the style and palette of Emil Nolde — but rendered inexpressive by its close toning. Coventry was brought up a Roman Catholic and there are echoes of the Turin Shroud in his picture, but it is really about distancing — as is so much of his work. This is art about art: Vermeer interpreted (badly) by Van Meegeren, reinterpreted through the filter of Nolde and then stuck behind glass to hold it even further away. Is it satire? Apparently not: ‘I don’t have a stance, I’m totally ambivalent. The viewer can make what they want of it; I just present it. With the white-on-white paintings, you can’t be sure whether it’s nostalgia for lost traditions or nostalgia for Modernism. There’s a kind of sympathy for both.’

Coventry’s studio is packed with paintings in various degrees of completion, and on a corner bookshelf are a number of oversize volumes. Two books on Churchill’s paintings catch my eye. Why those? ‘Because he did white-on-white paintings,’ says Coventry, ‘a technique recommended by Sickert. I saw them at his studio down in Chartwell. I liked them, then thought of copying them myself as part of all that Englishness series.’

Some commentators have identified Coventry’s work as a new and savvy form of history painting, managing as it does to encapsulate a dialogue between Modernism and English culture. He is seen as dealing with social issues, with vandalism and sink estates, drug abuse and prostitution. Another series of paintings, called collectively ‘Anaesthesia as Aesthetic’, is based on the treatment of shell-shocked soldiers by exposing them to soothing colours. (An idea he found in a book on colour by John Gage.) Yet another series reinterprets the colours and patterns of McDonald’s packaging as abstract arrangements of line and hue.

Coventry uses photography and found imagery, adjusts the image in his mind’s eye and then turns to his real enjoyment: the application of paint. ‘I don’t want to have to change anything. The painting only develops in terms of the quality of the paint. I like to build up the edges of shapes until they’re really thick, much as Sickert used to fill in an area with a green slightly different from the green underneath. It gives a kind of breadth to it.’ The brush strokes are applied almost on a grid, either vertically or horizontally, to emphasise the two-dimensionality of the surface of the painting. ‘It’s a play between spatial illusion and the surface.’

Framing is important to Coventry, who presents his oils behind glass. ‘I like the idea of a certain distance so that you can’t quite take in a painting. Reflections slow down the process of consuming the picture. I read somewhere 30 seconds is the maximum time that people spend looking at pictures.’ Certainly, Coventry wouldn’t consider using non-reflective glass in his frames. He wants viewers to get a glimpse of themselves to help captivate them, to hold them in front of his pictures. Francis Bacon also liked the idea of the viewer’s reflection becoming part of the experience of looking at a painting.

Coventry is beguilingly modest about his technical attainments. He doesn’t think of himself as a sculptor, because his sculptures are found objects he takes to a foundry to be made into bronze. His first was a broken tree. ‘I wanted to paint it like Caspar David Friedrich — an existential-looking snapped tree against the sunset, then realised I didn’t have the skills.’ But he has tried to develop his range as a painter — particularly in the ‘Echoes of Albany’ series. ‘It’s a big move from painting a rectangle to painting a figure, a real leap.

‘I remember something John Hoyland said when I was a student: you have to set parameters, because without them the energy that you have will just dissipate. I think that my parameters are quite tight; basically: don’t do anything too difficult!’ When I suggest that this doesn’t sound terribly ambitious, Coventry ripostes, ‘The thing is, it’s how well you operate within that, isn’t it? People who try to do ambitious things often fail. It’s far better to know your limits and operate successfully within them. Then you can be more ambitious incrementally.’ And that, it seems, is precisely what he is doing.

Comments