At Tate Britain this year, for the first time since 1926, nine of John Singer Sargent’s brilliantly painted and affectionately characterful portraits of the Wertheimer family have been displayed together in their own room. This was what the wealthy London art dealer Asher Wertheimer had always intended when he bequeathed these paintings to the nation. Some queried his generous gift on the frankly snobbish and anti-Semitic grounds that it was not for upstart Jewish businessmen to force their likenesses into a national collection. The Conservative MP Sir Charles Oman went so far as to say in the Commons that ‘these clever but extremely repulsive pictures should be placed in a special chamber of horrors and not between brilliant examples of the art of Turner’.

The Wertheimers were not merely Sargent’s patrons but also his friends, and in his absorbing new biography Paul Fisher persuasively argues that the painter had a particular affinity with those who, like himself, were cosmopolitan outsiders in British society or in other ways flouted convention. This was not, however, the image Sargent presented to the world. Rather as he had grown a beard to disguise his receding chin, so his immaculately tailored exterior was designed to convey unimpeachable respectability, a quality he is on record as having valued above all others. He had been badly shaken when Madame X, his portrait of the French adventuress Amélie Gautreau, caused a furore at the Paris Salon in 1884, but many of Sargent’s later paintings seem provocations in style or subject.

Sargent handed down no letters or diaries that shed any real light on his private life. This leaves his biographer in the uncomfortable position of having to speculate a good deal, and it is to Fisher’s credit that he proceeds more by suggestion than by assertion. Many of Sargent’s portraits, notably those of glamorous young blades such as Léon Delafosse and W. Graham Robertson who moved in homosexual circles of the period, are certainly open to interpretation, while the ‘stacks of sketches’ depicting male nudes indicate a more than academic interest in men’s bodies. Fisher regards the labels ‘gay’ and ‘queer’ as inappropriate to the times in which Sargent lived, and instead portrays the artist as someone who, though he had close women friends, principally enjoyed the company of other men, and formed relationships with some of them that went well beyond good companionship.

Many of these relationships Fisher terms ‘romantic friendships’ of the kind Sargent’s friend Henry James wrote about in Roderick Hudson. They sometimes resulted in drawings and paintings that seem charged with feeling, such as those of the ‘elfin’ Albert de Belleroche, with whom as a young man Sargent had shared a studio in Paris. Alongside his hugely successful public career, Sargent had in fact always made more ‘intimate and private’ drawings of clothed male friends and unclothed male models. Similarly, while the principal fruit of his appointment as an official war artist in 1918 was the vast and harrowing canvas ‘Gassed’ (1919), Sargent also painted tender little watercolours of naked soldiers bathing and sunning themselves.

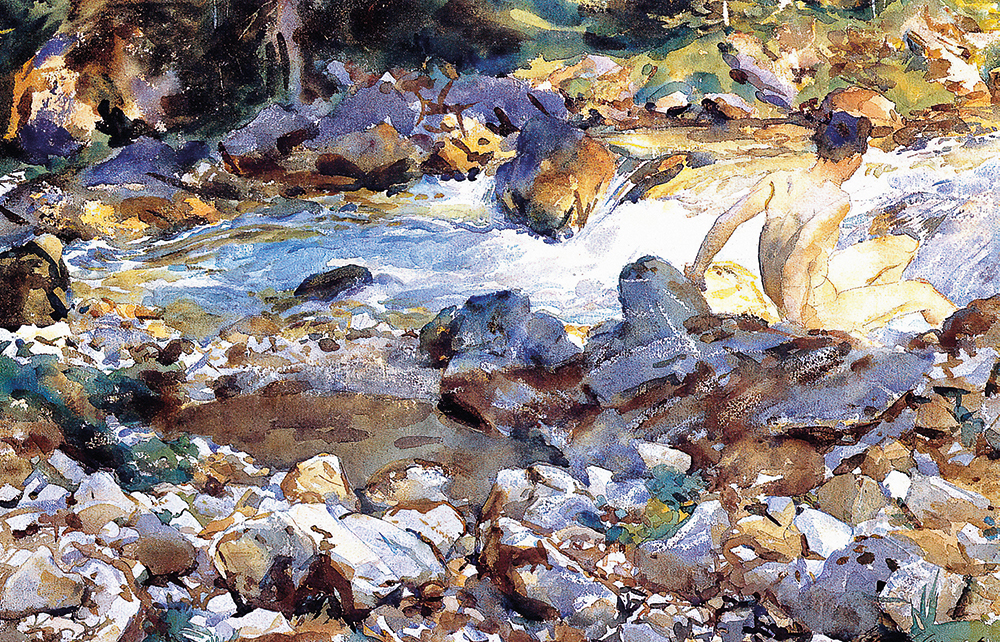

By this time his reputation as the most accomplished portraitist of the age had resulted in unwelcome commissions to produce likenesses of dreary politicians and military leaders rather than the forceful, unconventional women and ambiguous young men who were his preferred subjects. As a result, Sargent had increasingly turned to painting beautiful water-colour evocations of European cities and scenery, sometimes featuring his mother, sisters and nieces, who often accompanied him on his trips abroad. Elsewhere, young men appear, clothed and sometimes languorously asleep; but the innocuously titled ‘Mountain Stream’ (c.1912-14) features a fully naked figure entering the roiling water. This was Sargent’s Italian factotum Nicola d’Inverno, a former amateur boxer who spent some 25 years in his employ and was the subject of many nude studies.

Thomas McKeller, the black model Sargent employed while working on a decorative scheme for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts between 1916 and 1921, was also required to pose naked. As well as making many sketches of him for the allegorical and mythological figures in the mural, Sargent also painted a full-scale nude portrait. This full-frontal, indeed confrontational picture was never exhibited during his life and so may stand as a private pendant to the very public Boston scheme.

Fisher is both tactful and largely successful in describing the connections between these two strands in Sargent’s life and work, demonstrating convincingly that the painter’s private preoccupations often ‘crucially informed and underpinned’ his public art. Given that he is at pains to present Sargent in ‘his own times and context’, it is regrettable that he frequently dubs the painter a ‘workaholic’ and refers to ‘gender-bending’, ‘megaprojects’ ‘cutting-edge Parisians’ and ‘high-end lifestyles’. These are, however, small disfigurements in what is a very lively and illuminating reassessment of one of the greatest painters of his time.

Comments