Dry your eyes, Joanna Lumley, and try to move on. For the Garden Bridge was doomed from the start. Sure, it had all the hallmarks of an absolutely fabulous idea dreamt up by Patsy and friends in the early hours of Sunday morning after a humdinger of an evening on cocktails and Bolly. But by mid afternoon its shortcomings should have been uncomfortably apparent and the whole fuzzy-headed wheeze quietly forgotten. The mystery is that it’s taken so long – although even now, with the death-knell sounded, the bridge’s giddy supporters are petulant when confronted by unbelievers daring to suggest that, as a purely practical proposition, the idea stinks.

Let us for a moment set Joanna’s vision of loveliness to one side and look at what would have been the everyday reality of this ill thought-through project. First, the Garden Bridge was never a bridge at all. It was a private park that would have been inaccessible to cyclists at all times and locked shut at night.

On a dozen or so plum days of the year the park would have been closed to the hoi polloi and requisitioned by private firms for publicity and money-making purposes – despite being subsidised by £60 million of tax payers’ money and maintained in perpetuity at a cost of £3 million per annum from the public purse.

Its hoped-for ‘rus in urbe’ feel would have been spoiled by security cameras, bag checks, mobile phone surveillance technology (oh, yes) and by an army of busybodies in high-vis jackets empowered to take the names and addresses of anyone transgressing its stringent rules. While these rules proscribed such run-of-the mill activities as carrying balloons, flying kites and scattering the ashes of the recently departed they would almost certainly have been expanded to outlaw any activity deemed unacceptable to security personnel on the day.

As the number of people hoping to cross it went up, it would have become necessary to introduce a time limit. Those expecting a carefree stroll would have been told to get a move on unless they wished to fall foul of the uniformed stewards who, to repeat, would have been empowered to take names and addresses if visitors got stroppy.

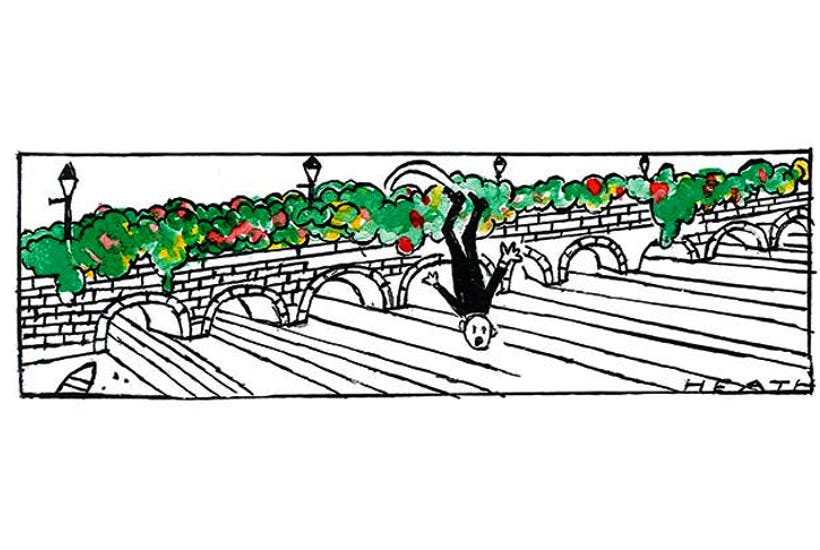

This was never, of course, the image suggested by the Garden Bridge’s official publicity. To the last it insisted that, in the perfect, prelapsarian world of its own imagining, leisurely knots of flaneurs would tastefully promenade among the orchids and the lilies, breathing the pure air of the countryside in the thick of the crowded metropolis.

But hang on a minute. If, as it had always been hoped, it had achieved landmark status it would rapidly have become a congested tourist magnet generating long queues on both embankments. Imagine the airport-style queuing paraphernalia erected along those embankments. Imagine the noisy summer queues. Imagine, in a word, the crowds that would have rendered any hoped-for peace and quiet a monumental delusion.

Things would not have been much different on the bridge either. The reality would have come as a rude shock to the public who had been encouraged to believe they would have been able to stroll freely in a verdant second Eden floating ethereally above the mighty Thames.

For the reality was that, at around 100 feet at its widest point (much narrower along the majority of its length), and with raised beds protruding into the space available, the park would have generated serious traffic management issues requiring, in fairly short order, a two-lane, one-way arrangement.

This, then, would have been the likely scenario awaiting you as you joined the expectant hordes; after an hour or so in the queue you would have been permitted to enter the park. Frisked for balloons and funerary urns you would then have been allowed to join what would have looked suspiciously like a second queue. This, however, would have been moving slowly but inexorably past the orchids and the azaleas towards the exit on the opposite bank. In the meantime your view of the exotic plant life on offer (if indeed it could ever have survived the heat generated by the press of so many bodies) would have been offset by the view of the backside of the person shuffling along a few inches in front of you.

At its holiday height the entire experience would probably have lasted about half an hour – or an hour if you had wanted to join the queue on the opposite embankment and face the whole dispiriting rigmarole for a second time in reverse.

To build the bridge, 28 mature trees would have been felled and the substantial green space they occupied on the popular South Bank built on. In their place would have stood an office block housing, you’ve guessed it, the Garden Bridge’s administrative HQ.

For this undemocratic land grab the people of and the visitors to London would have got precious little in return; at most a self-indulgent folly that had been hopelessly thought through and that would, for good measure, have obscured the incomparable view of St Paul’s from Waterloo Bridge.

Sadiq Khan is to be congratulated for pulling the plug on a scheme that has already swallowed £37m of public money; money that could have been better spent on half a dozen world-class communal spaces in and outside London rather than on a muddle-headed vanity project that should have been quietly binned the morning after the night before.

Comments