Archbishop Edward Benson was the ideal of a Victorian churchman. Stern and unbending, he was a brilliant Cambridge scholar and a dreamily beautiful youth. Older men fell over themselves to promote him, and he climbed effortlessly from one plum post to the next, rising almost inevitably to become Archbishop of Canterbury.

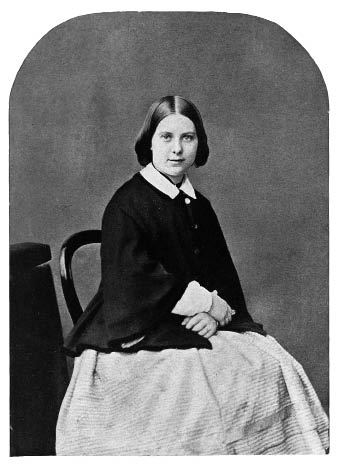

As Rodney Bolt shows in this fine book, Archbishop Benson’s domestic life was less than perfect. When he was 23, Benson chose an 11-year old girl named Mary Sidgwick to become his wife. She was his second cousin, and when she was 12 (which was at that time the age of consent) he proposed to her. They married when she was 18.

Mary Sidgwick later claimed that being a child wife meant that ‘I did not grow up’. Benson tried to control her in everything. He was humourless, didactic and dry. He bullied her about doing her accounts, and he suffered from black depressions which made him particularly unbearable to live with.

Mary rebelled from his domestic tyranny. She escaped into a world where Edward couldn’t reach her: into a succession of passionate relationships with women. ‘My God, what a woman!’ she would exclaim, and there would follow an intense friendship, ‘utter fascination’, a torrent of love letters and then what she called Schwarmerei, or inappropriate feelings, as she struggled with the carnal longing which she believed to be sinful. All this she recorded in her diaries, which form the material for Bolt’s absorbing account. It’s clear that Mary Benson wasn’t conflicted or ambivalent about her sexuality, and she felt no need to label herself as gay. She just happened to love women, but there was never any doubt in her mind that she was Edward’s wife.

When Edward Benson became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1883, Mary was a dumpy, prematurely white-haired 42-year-old. Witty and warm with a strong sense of the absurd, she was a surprisingly successful hostess. Gladstone thought her the cleverest woman in Europe. At Lambeth Palace, she had an affair with the tomboyish composer Ethel Smyth, but this turned into a complicated triangle when her daughter Nellie also fell in love with Smyth. Mary sailed serenely on, seemingly unfazed.

Archbishop Benson died suddenly and dramatically in church of a heart attack while staying with the Gladstones at Hawarden. Free at last, Mary hopped into the episcopal bed with her friend Lucy Tait. Lucy was the daughter of Edward’s predecessor, Archbishop Tait, and the two women shared a bed for the rest of Mary’s life.

Not a whisper about Mrs Benson’s carrying-on seems to have got into the press. The mind boggles as to what would happen today in our sex-obsessed church if, say, Mrs Rowan Williams was to be found in bed with the daughter of Archbishop Carey, but the Victorians wisely turned a blind eye to such matters.

Ethel Smyth once described Mary’s five children as ‘an unpermissibly gifted family’. Two sons, Arthur and Fred, gained effortless Cambridge Firsts, and poured out a flood of books. Fred (E. F. Benson) was the creator of Mapp and Lucia — light comedy which could hardly be further removed from the lofty endeavours of the Archbishop’s Victorian Church. Hugh, the third son, who also published prolifically, converted to Catholicism, and became a celebrity preacher and friend of the unsavoury Frederick Rolfe.

Bolt speculates that the compulsive writing of the Bensons was a way of deflecting tensions unresolved since their childhood. One daughter went mad and tried to kill her mother, and Arthur suffered from repeated breakdowns. All five of Mary’s children —including her two daughters — were gay. This is surely unusual by any standards, and if I have a niggle with Bolt’s account, it is that in his concern to show not tell, he doesn’t stop to ask the question why. If any family could benefit from some cod psychology it is the Bensons.

Mary Benson’s insight and intelligence make the story of her life and her extraordinary family a compelling one. I found Rodney Bolt’s engagingly written book very hard to put down.

Comments