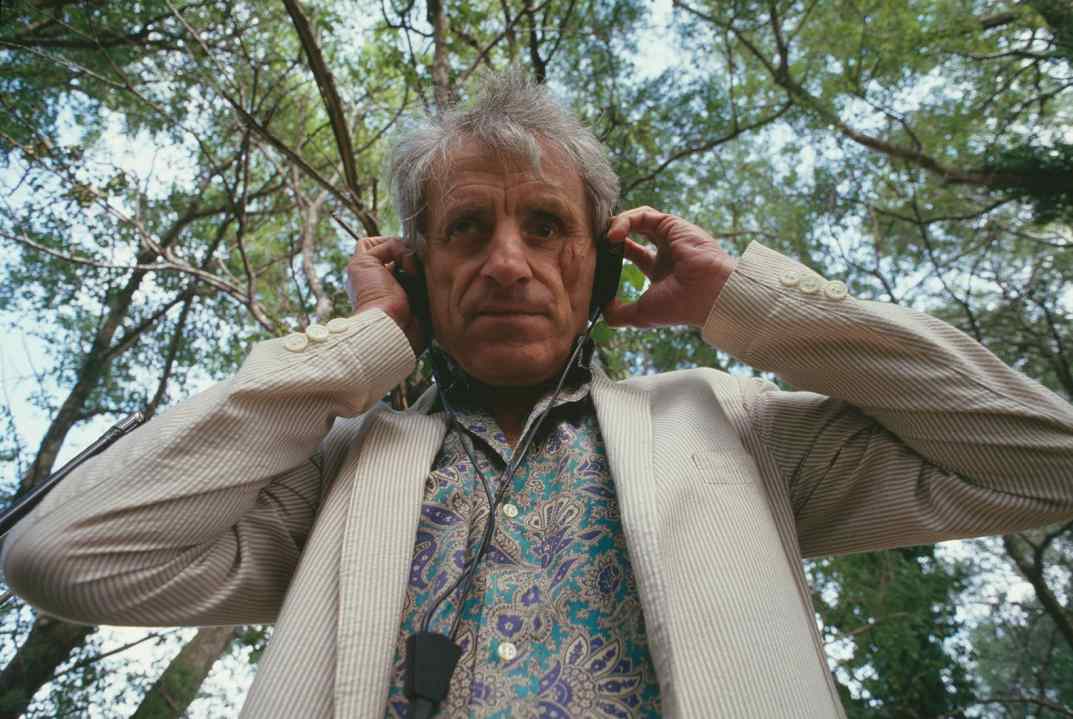

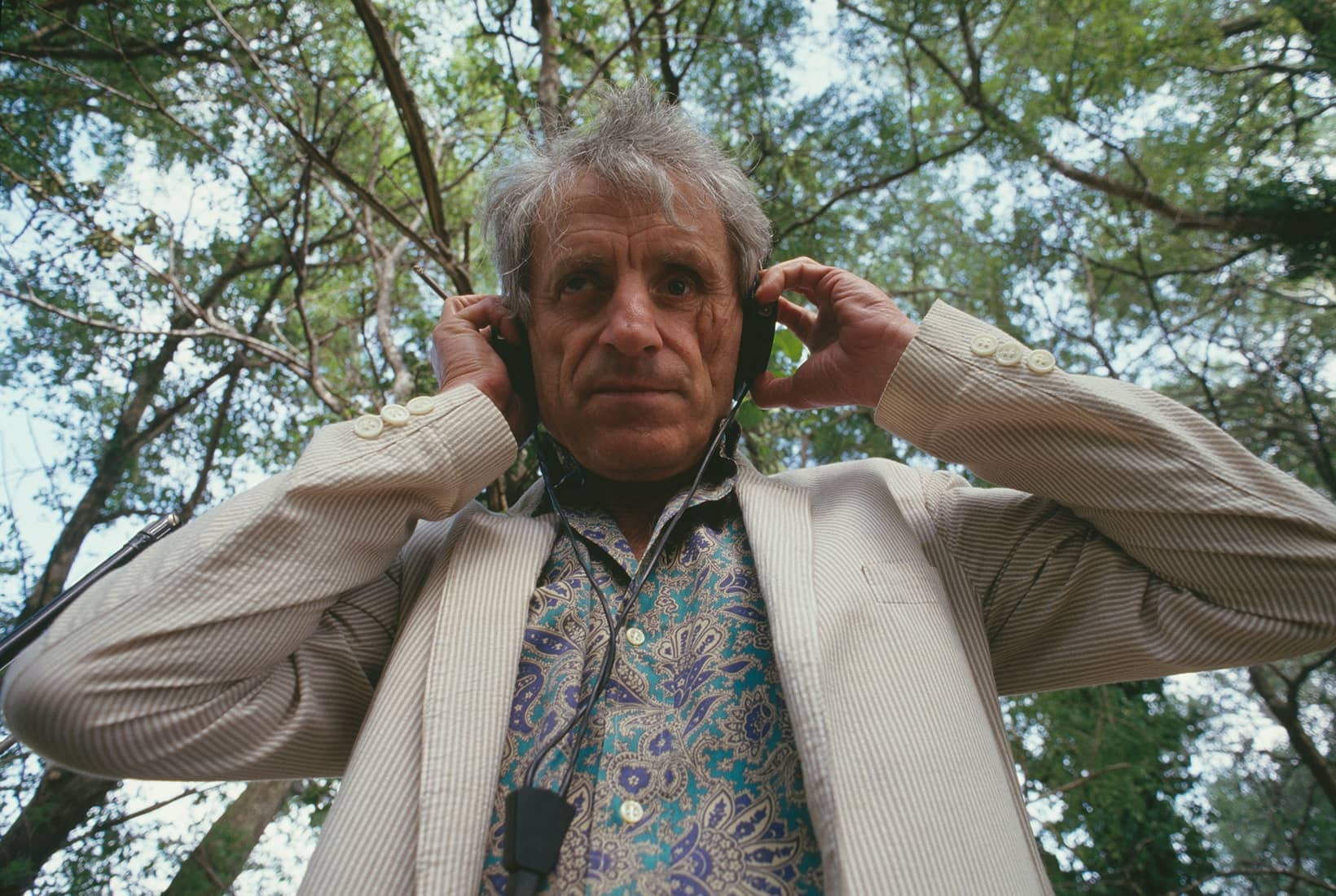

This year is the centenary of the birth of Iannis Xenakis, the Greek composer-architect who called himself an ancient Greek stuck in the contemporary world. His instrumental music at times suggests an alien species trying to communicate with us through our musical instruments, his electronic music a distressed animal on the receiving end of amateur dentistry. For his part, Xenakis said that music ‘must aim… towards a total exaltation in which the individual mingles, losing his consciousness in a truth immediate, rare, enormous and perfect’.

Of all the post-war European firebrands, Xenakis remains the most influential today. ‘Xenakis opened many fields of inquiry that are still vital, undiscovered, and brimming with possibilities,’ says Chaya Czernowin, music professor at Harvard and one of today’s leading composers. ‘These fields observe and listen to nature, beyond our immediate perception and psychological underpinnings, and connect to a primordial view of human existence.’

Born into a bourgeois family, Xenakis grew up to be a migrant. Having fought and lost an eye during the post-war Greek insurrection when shrapnel from a tank blast disfigured his face, he was condemned to death by a government who considered him a violent revolutionary. Fleeing Greece, he ended up in Paris, where in an improbable turn of events he became an architect working for Le Corbusier.

Of all the post-war European firebrands, Xenakis remains the most influential today

At the same time, inspired by the post-war developments in avant-garde and electro-acoustic music, Xenakis worked on becoming a composer. He developed a novel approach to orchestral and electronic music based on dynamic sound masses. The string orchestral work Pithoprakta (1955-56), for example, features shifting groups of pizzicato and struck wood, while the electronic work Concret PH (1958) samples and granulates the crackle of burning ember. Here, music is no longer about notes and chords but about clouds and torrents; no longer about stable harmonies but endless transformations.

Dr Elisavet Kiourtsoglou is an academic based at the University of Thessaly and a Xenakis expert. She ties Xenakis’s dual work in architecture and music to his ancient Greek heritage. Xenakis, she says, ‘used the term “alloy” to describe the relationship of arts and sciences. The term alloy suggests that both disciplines are almost melted together: you cannot define if architecture provides tools for music or if it’s the other way round.’ One of his most beautiful explorations of this analogy is at the Le Corbusier monastery in La Tourette, the undulating glass wall of which is proportioned like waveforms and designed by Xenakis.

Another Xenakis alloy is the Philips Pavilion. Designed for the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958, the spectacular architectural concept had also served to structure the opening section of Xenakis’s orchestral work Metastaseis. ‘In the Philips Pavilion, he uses hyperbolic paraboloid surfaces, inspired by the two-dimensional parabolas found in his graphic plan for Metastaseis,’ Kiourtsoglou explains. ‘This is important and innovative. The Philips Pavilion is the first building where these surfaces were used in three dimensions, as “walls” to cover the spectacle taking place inside. The Philips Pavilion is the precursor of what is called today parametric architecture, calculated through very advanced design programs and inspired by complex forms of nature.’ There is a straight line from Xenakis to the biomorphism of Zaha Hadid.

After Metastaseis premièred at the Donaueschingen Festival in 1955, the serialist coterie around Boulez snubbed him (their rivalry would endure for decades). In a critical essay, Xenakis had written that in early serialism, ‘Linear polyphony destroys itself by its very complexity; what one hears is in reality nothing but a mass of notes in various registers.’ To counter this he proposed ‘stochastic music’, wherein what mattered was not the old tonal rules or serial organisation, but rather a model acknowledging ‘the statistical mean of isolated states and of transformations of sonic components at a given moment’.

Xenakis subsequently brought to bear all sorts of exotic-sounding mathematical models on composition: sieves, arborescences, Brownian motion, Markov chains, Venn diagrams, Poisson distributions, metabolisms, game theory, much of it outlined in his 1963 book Formalized Music in all-but-incomprehensible fashion. Glissandi were prominent, replacing traditional harmonic sequences with continuous vectors. The string quartet Tetras is an example of this, continuously drawing us along despite lacking counterpoint and harmony. These complicated formalist techniques created music whose impression is viscerally wild. Xenakis said his musical reference points were ‘the collision of rain or hail with hard surfaces, or the song of cicadas in a summer field.’

Pianist and musicologist Dr Ian Pace, reader in music at City, University of London, often performs Xenakis’s dauntingly complex scores. ‘Xenakis showed it was possible to create a music which was composed according to highly systematic methods while still having a powerful emotional effect,’ Pace says. ‘The techniques were the means towards the end, rather than the end itself.’ Nonetheless, the music at times ‘could not be said to have been written with the practicalities of the instrument in mind. Some things are simply literally impossible. Some scores such as Synaphaï literally tell the performer to make choices of what to play from what is written. So it is not very instrumentally grateful, but the sounding result is worth it.’

In works such as the orchestral Crescendo Trilogy and chamber Wintersongs cycle, Chaya Czernowin uses intricate extended techniques and textural layering in marvellously inventive ways. Her sound environment of wisps and susurrations can suggest an ecological approach. The field Xenakis opened, she says, ‘is essential for my work, especially in opening the way to get out of a habitual commitment to phrasing, rationality, storytelling processes and one-dimensionality. Xenakis’s work, for me, is a kind of architecture of moving glacial or kinetic energetic terrains. In my work, I subvert, bend, press, expend, melt or mould such terrains while discovering their weirdness and their behaviour under risk. It is work focused on a clear architectural physicality, within which all its wildness is actually contained.’

For new listeners, which Xenakis works would Pace suggest trying out? ‘Eonta for piano and brass – once thought completely unplayable without massive numbers of rehearsals, now played by many groups – remains deeply important. Evryali and Mists have long been part of my repertoire, and stand as an archetype of certain types of music. But I equally love many of the choral works, especially as performed by James Woods’s New London Chamber Choir, and really elemental ensemble works such as Anaktoria or À l’île de Gorée for harpsichord and ensemble. Why? Simply because I get such a visceral experience from listening to them, in a manner I had never experienced before first encountering Xenakis’s music in my teens.’

Why, then – with the honourable exception of the BCMG and Royal Northern College (29 May, Birmingham) – are the UK’s classical music institutions ignoring the Xenakis centenary? Beyond the usual risk aversion, perhaps an answer comes from Xenakis’s ancient Greek ‘contemporary’ Heraclitus. The world, Heraclitus wrote, ‘ever was, and is, and shall be, ever-living Fire, in measures being kindled and in measures going out’. For a society sleepwalking towards Anthropocene catastrophe, maybe Xenakis’s blazing music is a little too real.

A day-long festival, >music & maths< Iannis Xenakis 100, will take place on 29 May at the CBSO Centre and The Exchange, Birmingham.

Comments