One of the great joys of the late Brian Sewell’s style of writing was his almost child-like bluntness. He had a three-year-old’s lack of tact when it came to saying what he thought of things, be it art or food or life in general.

The fact that he combined such unflinching honesty with intelligence, insight and erudite delivery was what made him one of the great critics. Always entertaining, occasionally right, cheerfully abusive, he showed us the world through his pince-nez, and it was both terrifying and magnificent.

Despite a weakness for baroque vocabulary, he was a master of economy. It took him only a few choice lines to demolish a victim: Tracey Emin was a ‘self-regarding exhibitionist’, Hockney a ‘vulgar prankster’, Banksy had ‘no virtue’, the work of Damian Hirst ‘I can sum it up as shiny shit’.

He also had the one thing that most critics these days lack: a healthy set of prejudices that he was not afraid to share. Not only did he have firm and unflinching views about most things, he was one of the last of a dying breed: the misogynist queer, the kind of man who not only preferred the company of men but actively disliked all contact with women.

‘There has never been a first-rank woman artist,’ he famously said.

Only men are capable of aesthetic greatness. Women make up 50 per cent or more of classes at art school. Yet they fade away in their late twenties or thirties. Maybe it’s something to do with bearing children.

In these tediously PC times, such spectacular rudeness seems almost refreshing. And it was by no means rare. My favourite Sewell story comes from an old subediting colleague of mine. Having filed to the copytaker (yes, this is an anecdote that goes back a few years), Sewell rang the desk to check that all was well. My friend assured him that all was. There was a pause. And then, in rich fruity tones, a request: ‘You won’t let a woman sub my copy, dear boy, will you?’

There are no women, or none of any note, in this little book of his, the last he published before his death in September of this year. Its subject: Henry Royce, a.k.a. ‘the man who built the best car in the world’, which according to this book was the Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost.

I’ll be honest: it’s not Sewell’s finest work. It pains me to speak ill of the dead, but there you have it. I’m not going to patronise his memory by saying otherwise. It’s certainly not a fitting coda for a writer of his calibre and intelligence.

The main problem is that it reads like someone pretending to be Brian Sewell — and not pretending very well, at that. The tone is irritatingly patronising and infantile, like an old-fashioned Ladybird book, or Enid Blyton at her worst. It has the feel of a book written by someone so grand and so grumpy that no one has had the courage to tell him it’s a little bit rubbish, not to mention quite a lot boring.

Bearing in mind that I am, despite the disadvantages of my sex, genuinely interested in cars and a huge fan of Sewell’s criticism, I struggled to wade through its 60 pages. Bar a few flashes of Sewellian charm (‘we are not yet on boiled-egg terms and should not be too familiar’; ‘claret, as wine from Bordeaux is properly called’) the prose is flat and grey on every page, and far too technical to be at all entertaining.

Weary, really, is how I would describe it. Very much a ‘will this do?’ sort of affair. I began with hope and got to the end with relief, rather like one gets to the end of tidying the kitchen cupboards.

I was certainly left with not a jot of curiosity about the car, or the men who made it. And Rolls-Royce cars were a subject that Sewell himself was both passionate and knowledgable about: ‘If you were a peasant confronted by a Phantom Continental,’ he once said, ‘you’d lie down in the road and let it run over you.’ There is none of that enthusiasm here.

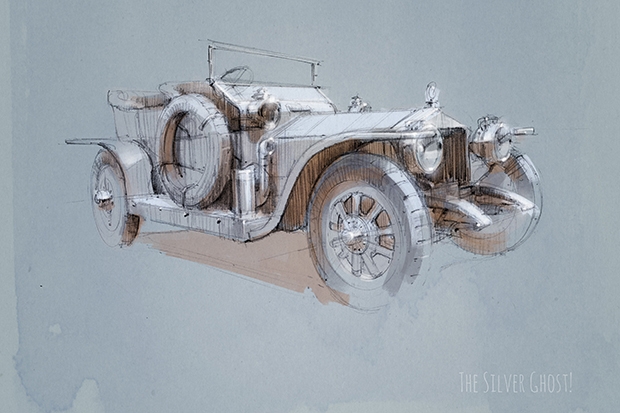

There are, however, Stefan Marjoram’s wonderful illustrations and technical sketches. By far the best thing about this little tome, they have a wistful, delicate quality to them, ghost-like on the page. Apposite in more ways than one.

Comments