Sometimes a small purchase gives an outsize amount of pleasure. I have felt this recently with a particularly robust pair of replacement boot laces and an especially bobbly, Italianate lemon.

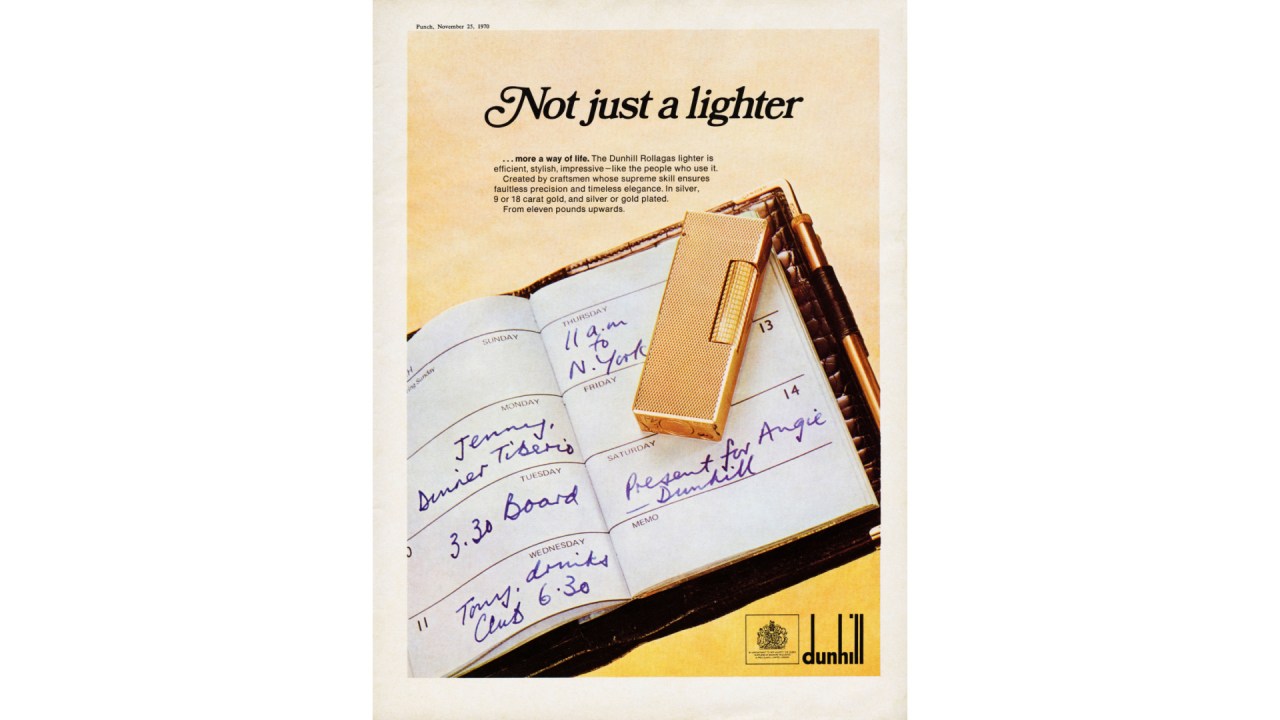

But most satisfying amongst all these small pleasures has been a lighter. Specifically, a Dunhill Rollagas lighter from eBay. Clearly an object of the 1960s, they are about £1,000 when new. This is far too much for me. However, they retail second hand for between roughly £25 and £200.

Of course, even £25 is obviously a great deal for a lighter. But, for this investment, you receive a fantastically luxurious object. The pleasure is very like that which I imagine comes with a classic car. It has art deco lines, being made of only two shapes: a cylinder set in a rectangle. It is superficially utilitarian – simple to use one handed, bevelled for grip, reduced to the essentials. And yet, just as the lines of a sports car are, at one level, just aerodynamics, the overall effect is ostentatious. It is heavy. It is nice to hold, and to feel, and to hear. Elements of it are pleasingly over-engineered: the lid mechanism could serve as a template for a bank vault door.

To flick the cylinder a quarter turn and have the flame dance up is to conjure the illusion of Audrey Hepburn, leaning in with her cigarette

Despite the weight and engineering, there is something rickety about it, too. They go wrong. They call out for being tinkered with. Enthusiasts sell repair parcels on eBay. Patient men on YouTube post long, soothing, videos of their repair jobs, old hands gently pushing jewellers’ screwdrivers into minute orifices on the case. Zen and the art of lighter repair.

Lying amongst the detritus of my desk, my Rollagas lighter sits like a portal to a more glamorous world, just as a vintage Ferrari amongst the clogged mass of motorway congestion seems to have its nose pointed at the country house, the dolce vita, the speedway – anywhere but back to a small garage in suburbia. To flick the cylinder a quarter turn and have the flame dance up is to conjure the illusion of Audrey Hepburn, leaning in with her cigarette, the evening lamps of Monte Carlo ablaze behind her. When being refuelled with butane, the case goes dramatically cold, very like how I imagine the refuelling of a rocket is. I am, briefly, a Denzel Washington, sweating, watching the fuel gauge under a red light as the thin skin of the Patriot missile quivers with the propulsive recharge. And the weapon analogy is not idle: the flame is capable of being pushed up to flamethrower level. I cannot decide whether this is a feature of the robust pre-health and safety era from whence it hails, a Q-branch bit of deadly gadgetry (they are, after all, extremely James Bond) or simply a sign my model needs repair.

The Rollagas is, in short, perhaps the defining artefact of the glamorisation of smoking. Not for the Rollagas the odd, regretted fag outside a pub. It comes from the time before cigarettes could hurt us and exudes confidence in the habit. It is a prelapsarian object, a celebration of something impossible to exalt in a world stricken with knowledge of the causes of cancer. Set against the grim cigarette packet, it is as incongruous as the happy bellow of the vintage car amongst the funereal, polite hum of electric vehicles, depressed into morbid silence by the terrifying awareness of global warming. It is the relic of a past innocence, a dead civilisation, and yet so recently expired as to feel the warmth from the body. As an object to contemplate on your desk, you could do worse.

Comments