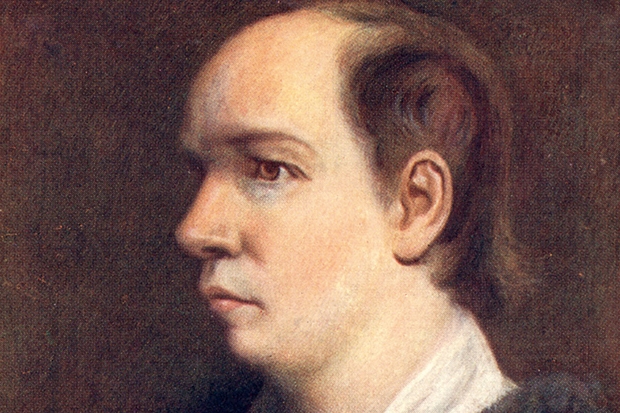

On 10 April 1772, the biographer James Boswell recorded in his diary that he had hugged himself with pleasure on discovering he would be dining with Oliver Goldsmith. This was not because he hoped to elicit from the Irish-born writer some fruity details for the life of Dr Johnson, the dictionary-maker, that he was planning to write (although Goldsmith did know Johnson intimately). On the contrary, Boswell, the literary groupie, was fascinated by Goldsmith himself. He devotes several pages of his Life of Johnson to him in an attempt ‘to make my readers in some degree acquainted with his singular character’. But, frustratingly, Goldsmith remains an enigmatic figure.

Boswell reports how Johnson said of him that he ‘touched every kind of writing, and touched none that he did not adorn’, which was praise indeed from a critic who enjoyed savaging those writers who did not meet his high standards of probity, meaning and cut-glass clarity. But Johnson also remarks that it’s ‘amazing how little Goldsmith knows. He seldom comes where he is not more ignorant than any one else.’ How could such a talented writer (who in his life of Beau Nash described the MC of fashionable Bath as a man who ‘dressed to the edge of his finances’) be also such a bore in conversation?

These contradictions perhaps explain why Goldsmith appears but dimly cast in Norma Clarke’s latest study of literary London in the 18th century. She argues that ‘there is no better writer to take us behind the scenes and under the surface of British literary culture’ of his period. But of Goldsmith himself we catch only glimpses, not helped by a lack of letters or a journal from which to determine his true character or the impulse for his talent. Just before he died (in 1774, aged 45) he began dictating his life story to his friend Thomas Percy, but as with most projects touched by Goldsmith, except his literary endeavours, Percy’s study was short, insufficient and delayed by 25 years.

Goldsmith, argues Clarke, arrived in Grub Street knowing exactly what he wanted to do, and it wasn’t just to make his name. He employed a variety of literary genres, only to subvert them as a way of seeking out the truth about patronage networks, colonialism and the exploitation not just of his native Ireland but of all those without powerful connections.

As for how writers were funded, he was determined to change the way that Grub Street functioned, where ‘hackneyed’ writers were in thrall to money-pinching booksellers or, worse, funded by watchful patrons whom they wrote to please.

Typically, even in this Goldsmith appears inconsistent. He signed a fairly lucrative contract with Ralph Griffiths, publisher of the Monthly Review, which kept him tied to Griffiths’s demands. Then, when that failed, he secured the monetary support and friendship of Robert Nugent, MP, later Viscount Nugent. Yet no one ever accuses Goldsmith of hypocrisy, perhaps because even with these arrangements he was always less than successful, often so close to debt that there were times he dared not leave the house.

Writing for a living, then as now, was always a precarious existence. Johnson himself only escaped the sponging houses of London by being granted a royal pension worth £300 in 1762 (for which he was much pilloried by his colleagues). The middle years of the 18th century were as difficult for authors as our own recent times, new technologies and a dramatic increase in the number of publications creating huge opportunities to make money by the quill but also severe competition for the spoils. Indeed, there is much in Goldsmith that has sharp relevance; his choice of a Chinese visitor as the narrator of his Citizen of the World essays, for example, was designed to point out through the eyes of an oriental observer how London had become a city in which culture was a commodity and instead of reading books people were interested in nothing but ‘sights and monsters’.

Clarke’s solution to Goldsmith’s elusiveness is to resuscitate several of his Grub Street contemporaries who she argues were the inspiration for some of his most popular characters. Writers like Samuel Derrick, who worked on a scholarly edition of John Dryden’s poems in four volumes but also kept Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies up to date, largely through his own after-dark researches (in which he was often joined by the young Boswell). Or John Pilkington, who funded his literary efforts by subscription, even persuading the Archbishop of Canterbury to cough up one guinea for a copy of his fictional memoir The Adventures of Jack Luckless (proposals for which were issued on 1 April 1758; note the date).

Goldsmith, though, shines through as the most interesting figure. We simply want to know more about him. He once described himself as ‘a gooseberry fool’, which does perhaps accurately convey the quality of his most popular works, She Stoops to Conquer and The Vicar of Wakefield. Both might appear like flim-flam but on reading have a tart piquancy.

Comments