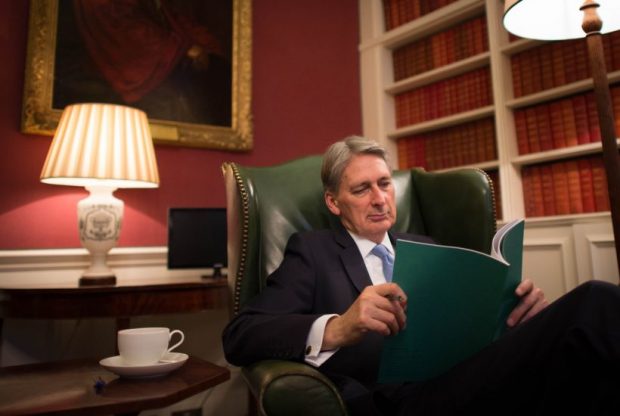

Facebook and Barack Obama have said they both want to tackle ‘fake news’ on the internet. The battle should start with government economic forecasts. Does anyone really believe the figures for economic growth up to 2020 made by the Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) and pumped out by Philip Hammond in his Autumn Statement? Growth for next year, claims the OBR, will be 1.4 per cent, down from 2.2 per cent. In 2018 it will be 1.7 per cent, followed by 2.1 per cent in 2019 and 2020 and two per cent in 2021.

How very precise. And how utterly improbable. What is the point in making these forecasts when they have proved so wide of the mark in the past? A year ago, the OBR forecast growth in 2016 at 2.4 per cent. It then downgraded its forecast to two per cent in March – and now says it will be 2.1 per cent.

Pick a growth figure of around two per cent out of the hat and you are likely to be reasonably close in most years. But it didn’t help the Treasury – which made these forecasts before the OBR was founded – foresee the 2008 crash. In June 2007, its central forecast for annual growth in the middle of 2009 was 2.5 per cent. There was a 90 per cent chance that growth would be between 0.8 per cent and 4.2 per cent. When the middle of 2009 came annual growth stood at minus 6 per cent – which wasn’t even on the Treasury’s chart.

Treasury forecast don’t tend to foresee recessions, even though they are a regular part of economic life. That makes them pretty useless from a practical point of view. However, the Treasury has made one past forecast for recession. It came this May in the second of two documents it put out during the referendum campaign. You can read it here.

It presented two scenarios for the immediate aftermath of a vote to leave the EU. In the ‘shock’ scenario, growth would be 3.6 per cent lower after two years. In the ‘severe shock’ scenario it would be 6 per cent lower. Today’s OBR forecasts have been treated as a shock downgrade in the government’s expectations of growth, yet compared with the Treasury document they amount to a huge improvement in outlook. If growth two years after the referendum – i.e. in June 2018 – was going to be between 3.6 per cent and 6 per cent lower than it would have been without the vote for Brexit, it would take the economy heavily into negative territory. The ‘severe shock’ scenario also included a forecast of 800,000 unemployed.

Yet the OBR says it expects growth in 2018 of 1.7 per cent – a long way from recession. It is a polite way, perhaps, of saying it thinks the Treasury’s scaremongering document in May was a load of cobblers. But then I wouldn’t expect too much from the OBR’s forecasts either.

Comments